Matt Seccombe spends much of his day sorting through roughly a million pages of horror. It’s his job to analyze documents in the HLS Library’s Nuremberg Trials Collection, one of the most extensive collections of documents from the trials of military and political leaders of Nazi Germany and other accused war criminals. He acknowledges that it is sometimes “nightmare-inducing reading,” but every dramatic and unexpected individual document he uncovers makes the job compelling, he says. Seccombe catalogs some of his findings, including those shared in the ten reflections below, in his blog Scanning Nuremberg.

Matt Seccombe has been making his way through boxes of trial documents — from prosecution and defense arguments, to captured materials from German offices, to trial transcripts — before they are digitized and put online.

An executioner reflects

In October 1941, Lt. Walther supervised the execution of a group of Jews and Gypsies in Serbia and filed a detailed report. He noted that everything went quickly the first day, but on the second day, some of his soldiers “did not have the nerve” to kill quickly. As for Walther himself, “one does not develop any psychological inhibitions during the shooting to death. However, these appear if one contemplates it quietly after a few days in the evening.”

Orders to kill civilians

In September 1941, upon instructions from Hitler, the senior military commander, Wilhelm Keitel, issued the “Keitel order” for the eastern front (Russia and Yugoslavia). All opponents in the occupied territories were deemed to be Communists, and since “a human life frequently counts for naught” in the region, deterrence required “unusual severity.” For any attack, “the death penalty for 50 to 100 communist[s] must in general be deemed appropriate as retaliation for the life of a German soldier.”

Fatal words

The most incriminating statement of the trials appears in Dr. Adolf Pokorny’s proposal to Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, that prisoners be chemically sterilized so that they could be used as laborers but would eventually die out. Pokorny was “[l]ed by the idea that the enemy must not only be conquered but destroyed.” Himmler made a note about where to start: “Dachau.” Because his plan was never carried out, Pokorny was acquitted.

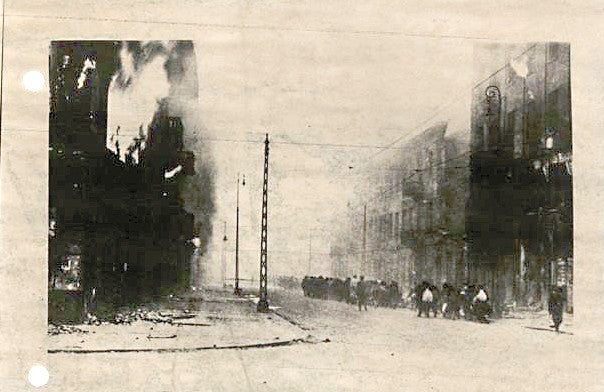

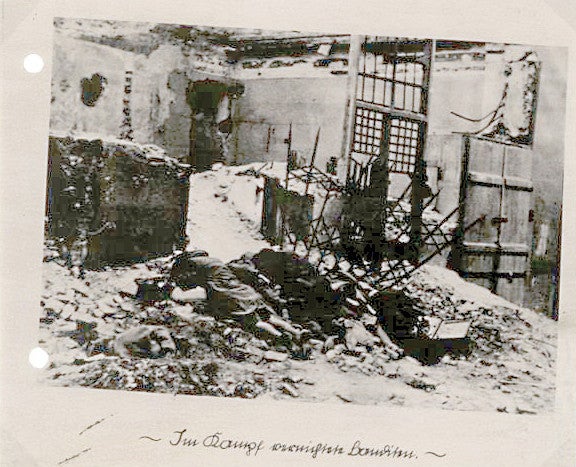

Destroying the Warsaw Ghetto

On Himmler’s orders, the Warsaw Ghetto was eliminated in 1943. SS Cmdr. Juergen Stroop was privately impressed by the Jews’ armed resistance, but officially he denigrated them as traitors and bandits in his report, “There Is No Jewish Ghetto in Warsaw Anymore.” The survivors were marched away as the district burned.

Prosecutors’ notes on defense documents

In two cases we have defense document books that had been used and annotated by the prosecution, indicating its response. One note was personal: “Oeschey a hypocrite?” One was strategic: “Object to entire book” as being irrelevant to the charges; the outcome is noted: “Overruled.”

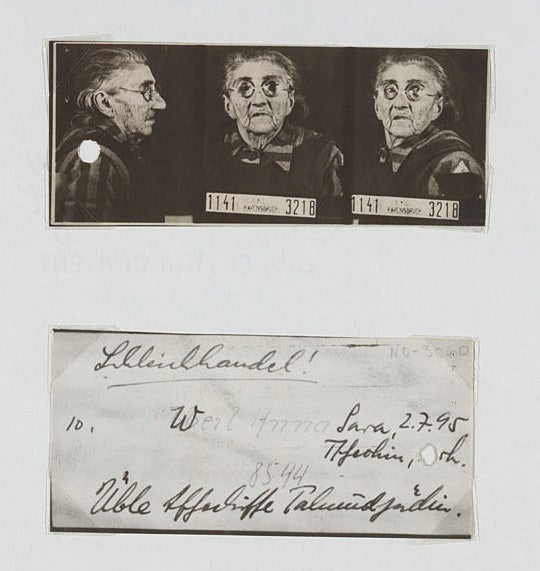

Selections for euthanasia

Dr. Fritz Mennecke of the Eichberg Mental Institution was tasked with selecting individuals for “euthanasia,” and his file contains photos and notes. Individuals selected were described as either having “a life not worth living” or being “a useless eater.” Among them was Anna Weil, diagnosed by Mennecke as being an “Unsympathetic Czech Talmudic Jewess.”

Curious words

One document refers to legal files that have been dealt with by “the electrical wolf” (with no further explanation). A German colleague suggests that this is a German term for a paper shredder.

A victim speaks

The prosecution made a public request in January 1947 for accounts of forced sterilization, and Inge Lorber was one of those who told her story: “They treated me like an animal that was led to the slaughterhouse.” She had a minor hip deformity, and lacked Nazi connections to protect her, so she was sterilized. Even if her evidence was not suitable for the trial, “I had to unburden my heart to somebody.”

Unexpected voices

Most of the 3,090-plus (so far) authors of the affidavits, letters, reports, orders, books, and other documents are ones you would expect: the leaders who issued orders, and the people who carried the orders out, or suffered the consequences, or bore witness. But there are also unexpected authors turning up—among them, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Vladimir Lenin, Col. George Ruggles from the American Civil War, Dr. Jonas Salk, Tom Paine, Plato, and the Brothers Grimm.

The werewolves

One defense affidavit by Hans Hammling claimed that in April-May 1945 in the German village of Grenzen, the newly arrived U.S. occupation force put up a poster warning that “for each soldier of the United States Armed Forces, who was killed by members of the Wehrwolf organization or the German population, 200 . . . Germans would be executed by shooting.” (The commander who had occupied Grenzen later testified that no such order for reprisal killings had been given.) Werewolves? A bit of research revealed that this was an SS idea to set up clandestine forces to harass and sabotage the Allied armies when they entered Germany and to punish Germans who cooperated. Little came of it, except perhaps making the Allied occupation regime more suspicious than it might have been.