Monica Monroe’s penchant for advocacy began at a young age.

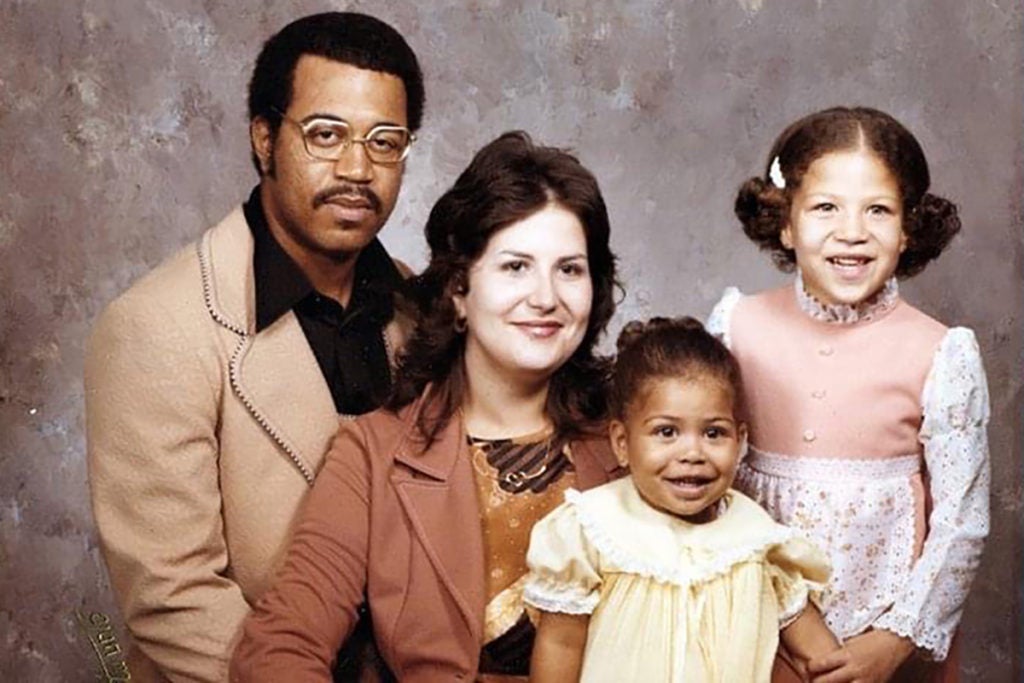

The daughter of a white mother and Black father growing up outside Pittsburgh, PA in the 1970s, she vividly recalls a night out with her family when she was about seven years old. “I remember going out to dinner one night and noticing an entire family at a nearby table was just watching my family,” she recalls. “They were just staring. And I knew why they were staring.”

“So, I turned toward the family — I could tell my parents were worried, I could feel everyone’s discomfort — and I looked at the other family and said: ‘Do you know the Ziploc commercial on TV where the two sides of the bag opening are blue and yellow, but they zip together to make green?’ My point was: ‘We’re a family just like you.’”

As a mixed-race couple, her parents’ journey had been difficult. In 1970, three years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia (1967) that bans against interracial marriages were unconstitutional, her parents had traveled to the former capitol of the Confederacy to tie the knot. “They were doing something that was illegal just a few years prior in many places and still not widely accepted,” she says. And despite the foundational civil rights victory, Virginia officials turned them away. “Virginia said that they were unable to marry them, alleging they did not fit the requirement, and sent them down the road to Maryland instead.”

Despite the challenges, Monroe lights up as she discusses her family and childhood. “I come from a very loving, very close-knit family where what was really valued was how people treat each other. We would sometimes question whether we would be able to make our ends meet but we never questioned whether we were loved.” Her father worked in the Pittsburgh steel mills until he retired, while her mother focused on her and her sister’s educations, often working and volunteering at their local school.

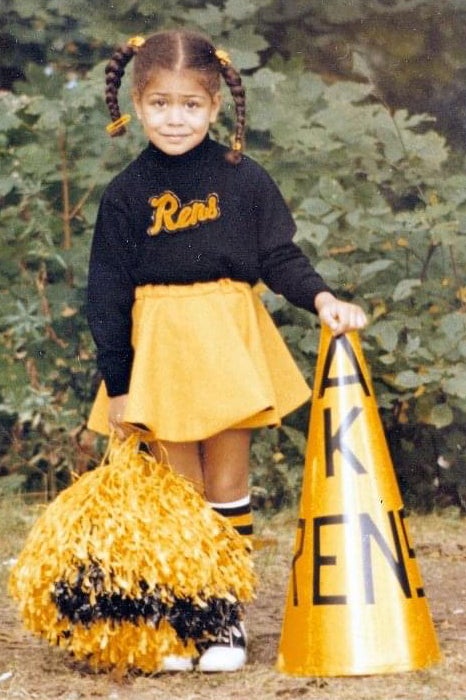

Somewhat apologetically, she explains that she comes from a family of Pittsburgh football and hockey fanatics. “My father was a steelworker, and I am a diehard Steeler fan. I always wore black and gold growing up. So, I love New England, and I’m going to see the Celtics in the Garden for the first time this weekend, but I will always be rooting for the black and gold Steelers, Pirates, and Penguins.”

Monroe’s lifelong desire to fight what she saw as injustice and her passion to serve others — a perspective that would ultimately lead her to study law – emanates from another childhood incident involving a young man she calls her brother.

“I was around eight when my mom found a child sleeping on our porch,” she says. “He was a child who was experiencing trauma. My mom brought him into the home. It was winter and it was cold. My mother wanted to adopt him but for various reasons, we couldn’t.” Soon, social workers came to take him away. “I remember seeing his pain. And also, my mother’s pain because they were basically taking him where you took kids who had committed crimes. He committed no crime. They just did not have a place for him. And I remember saying I will ensure that I will always be in a position to advocate for others.”

“At the time, I didn’t know really even what that meant,” she admits. “But on TV, I saw lawyers, litigators, who could stand up and argue on behalf of someone. And I decided I wanted to be able to help people in the same way. That was life changing for me, absolutely life changing.”

Monroe and her family stayed in touch — visiting him on weekends and having him over for Christmas, and they are still in touch today. His struggles as a child, and with the system that compounded his trauma, ultimately became the focus of Monroe’s essay when she applied to law school years later.

The desire she felt that day to support others, she says, seeped into every aspect of her life, however unlikely, including high school cheerleading. “From a very early age, I wanted to be a cheerleader,” she explains. Pointing to an old photograph of herself wearing the gold and black uniform of her little league cheer team, she says, “When you look at it, you can see I’m an introvert, a shy kid who is kind of scared, but that I still wanted to show up for other people.”

When people told her that she couldn’t be a professional cheerleader, she disagreed: “No, no, no, you can,” she says, responding to the naysayers. “You’re not necessarily putting the uniform on every day, but you have the desire to support and uplift other people and to help them find their passion and their purpose. And that’s what I wanted to do.”

Her decision to move to Boston for college was in part influenced by her mother’s love of New England, despite never actually having visited the area, and a chance meeting in 1989 with a person connected to the region who gave her the impression that Beantown was a center of cultural diversity, acceptance, and inclusion. It was only later that she read about the city’s difficult racial history. It also didn’t hurt, she jokes, that her favorite band at the time, New Kids on the Block, was from Dorchester.

Despite falling in love with Massachusetts, Monroe decided to attend George Washington Law School. “I still laugh at how horrible I looked from crying coming off the plane flying from Boston to D.C. because I didn’t want to leave,” she says. But she dove into her new environment, finding opportunities to serve others along the way, eventually becoming the head of the GW Law Black Alumni Association.

She says her favorite part of being a law student was how it challenged her, for the first time, to reconsider her own belief system. “I remember discussing the death penalty for the first time in a criminal law class,” Monroe says. “Where I grew up, you believed in the death penalty; consequence for actions made sense to me. I realized I believed things because my parents held certain beliefs. But then I went to law school and started to peel back some of the layers. I gained deeper insight into how it was implemented and started formulating my own opinions.”

She loved that law school was giving her not only the tools to succeed professionally in many fields, from government and public interest to corporate law or business, but that it also provided her with the “skill set to reexamine why I thought the way that I did, and what that was grounded in, what was my own beliefs.”

Her worst memory from her time at GW? “I didn’t like the pressure I put on myself.” As a first-generation college and law student from a middle-income family, Monroe felt the need to succeed, not only for herself but for those who had helped her on her journey. “I wanted to be able to repay my parents for all the sacrifices they had made for me. I was carrying the weight of my entire family. I put that on me. They never did.”

“It’s something that many first-generation students, first professionals, and people of color experience,” Monroe explains. “How can I pay it back? And how do I pay it forward?”

“I truly want everyone to feel that same innate sense of belonging that I felt the day I returned to start working at HLS.”

She believes that everyone has a simultaneous desire to succeed and be accepted, while maintaining ties to the community from which they came, no matter where they are or what they’ve achieved. That’s a philosophy she says she brings with her in her new role at Harvard Law. “No one ever wants to feel that they don’t belong, right?” she says. “No one wants to feel that they aren’t still tied to their roots, no matter where they ascend to. Everybody wants to still feel that love. And there’s nothing like hometown love. There’s nothing like family love.”

A deeply spiritual person, Monroe says her career path since law school has been guided by faith, opportunity, and a commitment to service. In 2007, while working at a small Black-owned law firm, she was offered the post of assistant dean of students at her alma mater, The George Washington University Law School, a job she loved and in which she thrived. “I found helping the students and those around me immensely rewarding. I knew I had found my calling.”

“And then I got an email in 2016 from Penn Law about their dean of students role,” Monroe says, explaining why she decided to take the new opportunity. “I wasn’t looking to leave GW. But I always have prayed that whatever God desires of me, despite whatever fear I may have, or whatever circumstances may be going on in my life, that I show up for whatever I feel I’m being called to do. I try to always have faith over fear.”

The mother of two boys, 7 and 10, who are into playing music (“we just had our first piano recital”) and sports (soccer and basketball, primarily), Monroe is most proud of how they interact with others. “They are just fun, and they love people,” she says. “The best thing that comes out of the parent-teacher conference is not necessarily the grades, but when they say that your kids are kind, and that they get along with all the other kids. That, to me, is better than any straight-A report card that they could have.”

Today, Monroe is thrilled to be back in the Boston area and particularly to be serving Harvard Law School students and faculty. “I remember coming off Storrow Drive in 1991 when I was a freshman at Boston University and this feeling I had that I was where I was supposed to be, that I was home. Fast forward to February 21, 2022, the day before I started my job at HLS: I was almost at the exact same place but I didn’t go off Storrow drive. I kept going straight to Cambridge. And I exhaled. I realized for 27 years I have been looking to return.

“It is my sincere desire to honor the opportunity I have been given at Harvard Law School. I seek to fully embrace my time here and to help foster and support this amazing community of students, faculty, staff, and alumni. I truly want everyone to feel that same innate sense of belonging that I felt the day I returned to start working at HLS. It feels so great to be here and I am beyond grateful for this blessing.”