Conversations surrounding the 2016 U.S. presidential election often invoke references to “fake news,” Russian interference, data breaches, and the impact of various social media platforms on the divisive outcome. A new book from researchers at the Berkman Klein Center (BKC), with its origins in a 3-year study of the media ecosystem surrounding the election, disrupts this narrative.

“Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics,” by Yochai Benkler, the Berkman Professor of Entrepreneurial Legal Studies at Harvard Law School and faculty co-director of BKC; Robert Faris, the Research Director at BKC; and Hal Roberts, a fellow at BKC, provides the most comprehensive study of the media ecosystem surrounding the 2016 presidential election to date.

“The idea of this book was to wrestle — really starting just after the election, even though the work started far before that — with what just happened? What the heck just happened in our country, to our media system, to our democracy?” Roberts said at a book talk on Oct. 4, moderated by Martha Minow, 300th Anniversary University Professor at Harvard.

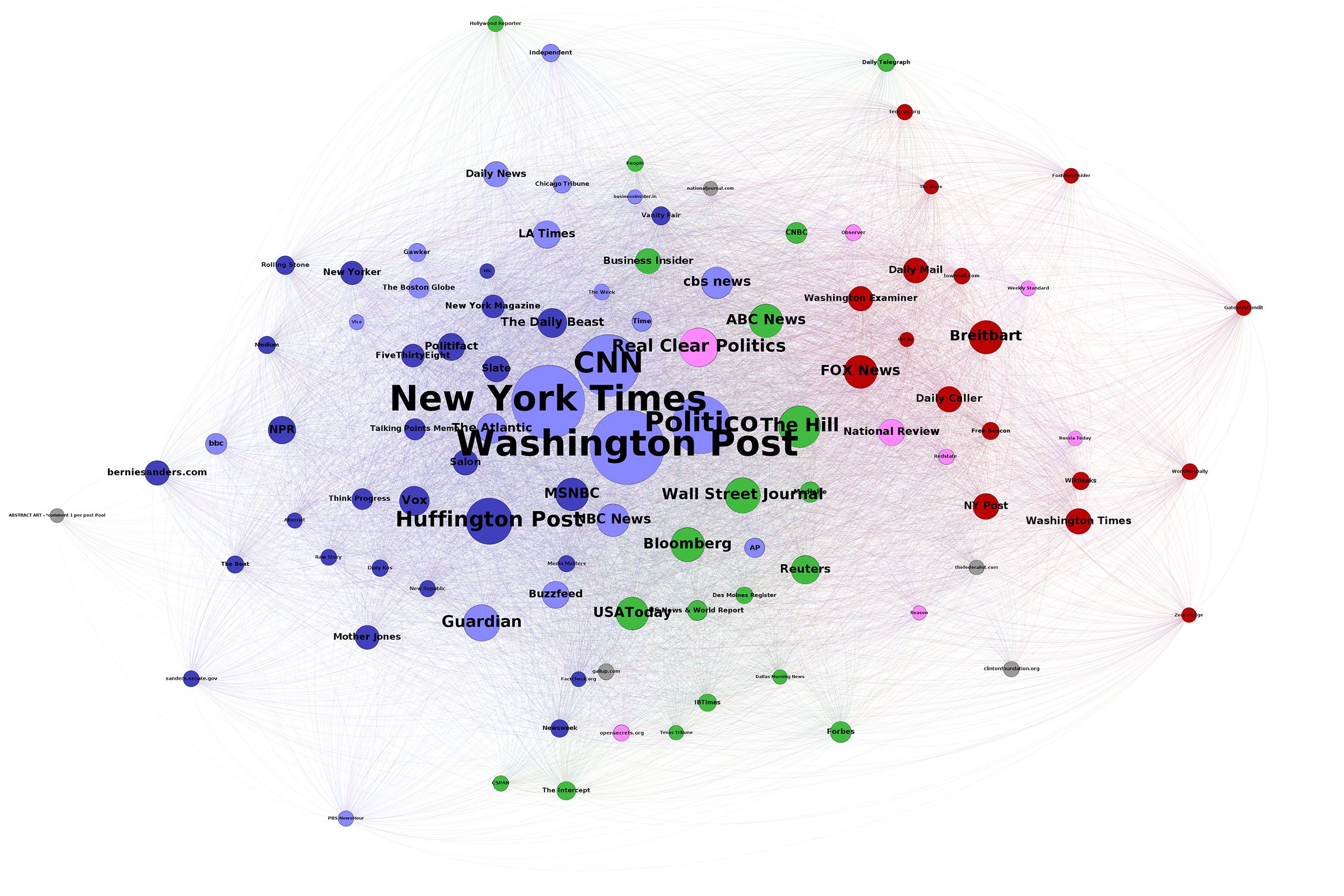

A major contribution of the book is what the researchers deem an “asymmetric polarization” model that stems from their research on partisan media ecosystems. The model, created with data from the media sources most-cited during and after the election period, shows that left-wing media outlets are more closely aligned with centrist media outlets, though the right-wing media sources are much more skewed and “are operating in their own media world,” Roberts explained. The researchers found that this pattern was evident during the election and that it was even more pronounced during the first year of the Trump presidency.

Asymmetric polarization was consistent across different platforms; it was found in analyses based on cross-media linking and in media sharing patterns on Twitter and Facebook.

“There are clearly two sides, and those two sides are not the same. The right is more insular; it’s more extreme; it’s more partisan,” Faris said of their findings. “That’s not a subjective opinion; that’s an empirical observation. And much of what we try to do in this book is to document that and understand what it means and how it’s reflected in different behavior.”

The book is grounded in a three-year study, which ran from April 2015, the start of the election cycle, until November 2017, to capture the first year of the Trump presidency. The research draws on four million online media articles sourced from Media Cloud, a joint project between BKC and the MIT Media Lab, but also includes data from offline media coverage, and from social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook, among others. The researchers also draw on previous work on media consumption trends and trust in institutions to contextualize their findings.

In addition to studying the current media ecosystems, “Network Propaganda” also explores the history of political communications in the United States and the rise of different trends, such as radicalization, and the creation of a market for outrage.

“We go through a good bit of the media history and describe how changes in technology, changes in law and regulation, and changes in political culture, all worked to reinforce each other in a long-term feedback effect to change the fundamental economics of the outrage industry,” Benkler explained, tracing its genesis back from the 1960s, to the rise of Rush Limbaugh in the early 1990s, and the creation of Fox News.

“Network Propaganda” examines media coverage surrounding major events, and topics of media coverage during the election time span, including disinformation–dubbed “fake news”–and how it is spread and consumed. The book also examines spikes in media coverage, like the one at the start of Robert Mueller’s special counsel investigation into foreign interference in the 2016 election. Case studies illustrate the researchers’ findings throughout the book, offering in-depth analysis of how trends in partisan media have evolved over time to their present state, and how media outlets are grappling with concerns of trust.

“The thing that most surprised us, and to us seems to be most contrary to the prevailing narrative of the moment, is that it’s professional mainstream media — both in its professional centrist model, and in its highly commercially successful right-wing model — is the scaffolding on which everything else is built,” Benkler said.

“Network Propaganda” is an open access title and available to read for free online. The entire book talk is available, below, or on the Berkman Klein website.