It began with the stroke of a pen: President Donald Trump’s signature on a January executive order banned entry into the U.S. by people from seven predominantly Muslim countries. Travelers were detained at airports. Students were unable to return to their schools. Impending travel for an Iranian baby’s heart surgery in Oregon hung in the balance. With airports in chaos and little information about their loved ones, families separated by the executive order pleaded on camera for the opportunity to reunite, awaiting a resolution many of them were unsure would come.

Then the lawyers showed up. They arrived at Boston’s Logan Airport carrying their laptops, turning airport terminal tabletops into makeshift offices, handwriting a habeas corpus petition for each individual in need. Law students clustered around a power outlet to coordinate the effort. Within 24 hours, attorneys around the nation were questioning the legality of the president’s action.

In Cambridge, the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program hummed with activity late into the night as students worked on amicus briefs and human rights abuse documentation for clients. Founded and directed by asylum scholar and Clinical Professor Deborah Anker LL.M. ’84, the Harvard Law program has involved students in the direct representation of asylum seekers and refugees for more than 30 years. In the wake of the November election, it mobilized to strengthen protections for that population.

More than 400 students enrolled at Harvard have now joined the HIRC-based immigration awareness effort, called the Immigration Response Initiative. Assignments range from local community outreach in the form of webinars and information sessions for undocumented people, to legal research, litigation support, and legislative advocacy. Some of the students involved in the initiative had never considered practicing immigration law. Others have been familiar with the realities of immigration since childhood. Here are some of their stories.

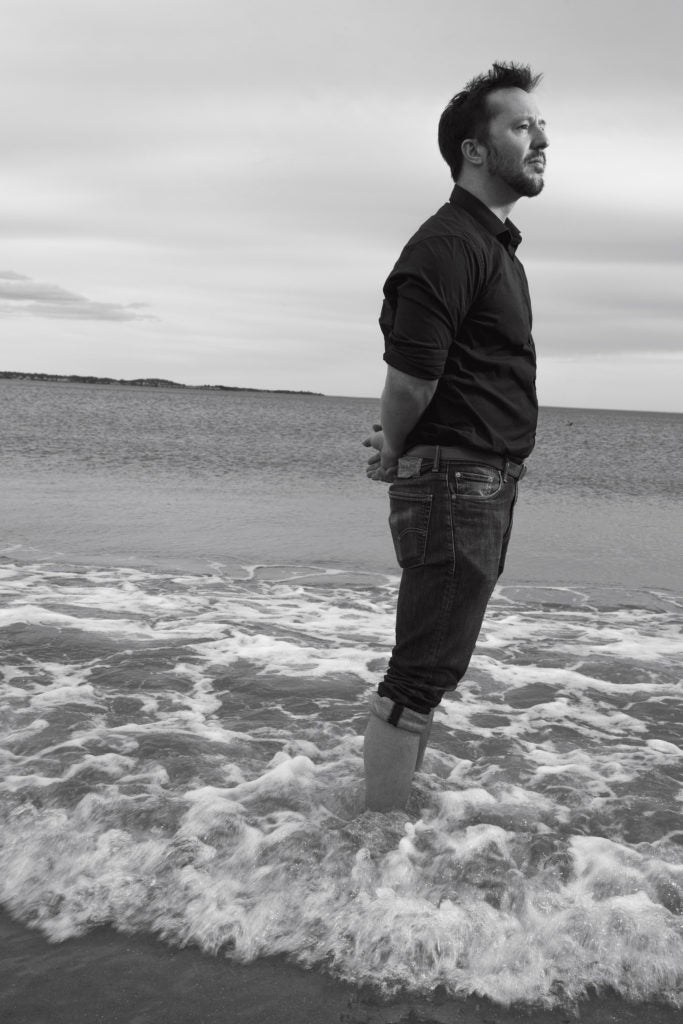

Nathan MacKenzie ’17 was inspired by what he saw in Logan’s Terminal E, but his interest in immigration law began not at an airport, but on a boat—during his nine years in the Coast Guard.

“If we picked up Haitian folks in a homemade raft, 99 times out of 100 they would be back in Haiti the next day without any sort of interview or any sort of adjudication,” he recalls. “I thought that there was something just fundamentally unfair about the way that the Coast Guard was used to deny people the due process that they would receive if they reached U.S. soil.”

“I hope that every law student goes through a similar program so that they learn some humility. You might be a big shot someday, but everyone that we’re dealing with is a person. They are worthy of respect and worth being treated with dignity.”

There’s 80 miles of open ocean from the Dominican Republic to Puerto Rico, and sometimes cutters like MacKenzie’s would arrive too late to save the migrants crossing the Mona Passage in their homemade boats. Occasionally the makeshift vessels would overturn and some of the occupants would drown. “You see what people are willing to put themselves through to try to get here, and then you see how the law treats them. For a nation of immigrants we’re not very forgiving of people trying to immigrate now. Unless you happen to meet very specific requirements, you’re almost undoubtedly deported,” he says.

At HIRC, MacKenzie has worked on two amicus briefs. The first was filed in support of Darweesh v. Trump, a challenge to the January travel ban on behalf of two Iraqis detained at Kennedy Airport and threatened with deportation by the U.S. government, even though they had valid visas to enter the United States. The plaintiffs argued that their detention, based solely on the executive order, violated their Fifth Amendment procedural and substantive due process rights as well as U.S. immigration statutes. MacKenzie was also part of the research team working on legal arguments about how courts should interpret certain provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act for the amicus brief submitted in the case International Refugee Assistance Project v. Trump, a legal challenge to the executive order’s drastically reduced cap on immigration.

MacKenzie sees his work with the clinic as a cornerstone of his development as a lawyer because of its ability to teach empathy. “HIRC is important because it teaches incredibly privileged law students, who are about to get cloaked in even more privilege, humility and compassion,” he says. “You’re dealing with people who are seeking asylum—some of them have suffered so much that they fall within the definition of what the entire world has said is an unacceptable situation.”

Aparna Gokhale ’17 grew up in Flushing, New York, one of the most diverse communities in the United States. Her family emigrated from India when she was 7 years old, and when she decided to pursue law, she wanted to address issues that affected her neighborhood. “Many of my friends are immigrants or first-generation Americans,” she says. “Being tapped into [that] community means always being aware of what’s going on in immigration, and that’s why I got involved in the clinic.”

Many of Gokhale’s activities on campus have revolved around issues of racial justice and inclusion as well as racial equality in education. Her work for HIRC has involved asylum seekers. Her goal, she says, has been to promote equality for immigrants coming into the country, regardless of their backgrounds. “The stories you see on television are often [about] exceptional immigrants,” according to Gokhale, and the message is that we need immigrants because they are doctors or engineers. That is juxtaposed with the depiction of the “villainous immigrants” who would be stopped by a wall or detained and deported by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “These are larger-than-life caricatures on both ends of the spectrum,” she says, “and it does a disservice to communities of hardworking people trying their best to make a good life for themselves and their families.”

In her work as a law student and lawyer, Gokhale wants to bridge the gap she sees between what the legal community provides and the power of communities when they mobilize and advocate for themselves. She credits HIRC’s holistic approach, including competency conversations and trauma-sensitive interviewing tools, with providing her with some of the skills she feels she will need. After graduation Gokhale will return to New York City to work in corporate litigation, but she also plans to continue doing asylum work on a pro bono basis.

Andrew Hanson ’17 wasn’t enrolled in HIRC, but after getting involved with the amicus brief in support of Darweesh v. Trump, he went on to work on other Immigration Response Initiative assignments as they came through on the law school’s listserv.

“Now that I’ve gone through the legal immigration process and this complicated complex of forms and files and having to navigate this maze without anyone getting in trouble or having to leave the country – it’s not as easy as particular outlets of the media might make it out to be.”

Hanson, who served in the Marine Corps, has spent much of his time at Harvard Law studying national security. The executive order brought up related issues. “I’d taken some classes where we talked about the broad authority that the executive branch has and the discretion afforded to the president under the Immigration and Nationality Act when it comes to national security,” Hanson says. “I wanted to understand what some of the challenges to this type of authority [are], like the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses.”

There is also personal motivation for Hanson’s involvement in HIRC. “My wife is an immigrant. All of my in-laws are immigrants,” Hanson says. His wife, who emigrated from Mexico, is now a naturalized American citizen. “There are definitely members of my family who, because of this administration and the policies and approaches that they’re taking, fear for their future,” he adds. “Working on the issues with the clinic allowed me to use my expertise to ease some of the fear.”

While Hanson plans to work in white-collar defense after graduation, “there’s a vibrant, active pro bono sector at many of the big private firms,” he says, “and that’s something that I want to incorporate into my work, to help people that are like my wife or in-laws.”

“I was advised that if I was going to do this type of work, I needed to see what was happening at the border,” recalls Tess Hellgren ’18. Last summer that is where she went, dividing her time between New Mexico and Texas, working to represent detained immigrants.

Hellgren spent part of her summer in Dilley, Texas, at the South Texas Family Residential Center, a 2,400-bed facility that holds undocumented asylum seekers, mostly women and children. It is the largest immigrant detention center in the United States.

The experience made it clear to her, she says, that the problem didn’t start with the current administration. The family detention center was opened in 2014 by President Barack Obama ’91 to staunch the flow of undocumented immigrants fleeing northern Central America.

“We saw mothers and children locked up, and it just doesn’t fit with any notion of justice,” she states. “All they’ve done is cross the border to try to make a better life. Many of them are so traumatized, either in their home country or by events that happened on their way to the United States, and the way we reward their survival is by locking them up.”

As she helped to prepare women and children for their asylum interviews, Hellgren listened to them describe the poverty, exploitation and extreme violence they were fleeing.

When it was time to return to Cambridge, she took what she learned along the southern border and applied it to her studies at HLS. This year at HIRC, Hellgren was able to represent a client at her immigration court asylum hearing. She prevailed.

“The feeling when you win a case, to be able to tell your client that they’re able to live their life in this country, is empowering. To have some victories like that, especially in an immigration context …” Her words trail off. “There’s such a need.”

Hellgren isn’t sure what the next executive order will bring. She notes that the clinic was doing a lot of work before the election, and she knows they’ll continue pushing the immigration advocacy conversation forward, with added urgency: “When we’re needed, we’ll show up.”

The Immigration Response Initiative “came out of conversations HIRC attorneys had with clinicians at other universities,” says Amy Volz ’18, a co-organizer of the initiative. “We created this list where people could sign up online. [There are] 10 different projects, and within that first week we had 300 people,” she recalls.

The projects include helping local college students renew their Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals applications, doing legal research to help clients prepare for potential litigation and engaging in local legislative activity. One project involves a series of Know Your Rights workshops. “We’re working with organizations within the Boston community,” says Volz. “They’re working with groups who know the populations and where the work is most beneficial. Yesterday we went to an elementary school in Somerville to do a Know Your Rights presentation with parents. It provides the chance to reach a large number of people, even though you couldn’t take them all on as clients because of resources.”

After graduation, Volz plans to continue serving clients in immigration matters. She is frustrated by the way people talk about immigration: “I think there’s a lack of empathy and understanding of people’s personal stories, and reasons why they’re coming—either as families or sending their children. What would make a parent send a child through this process unaccompanied?”

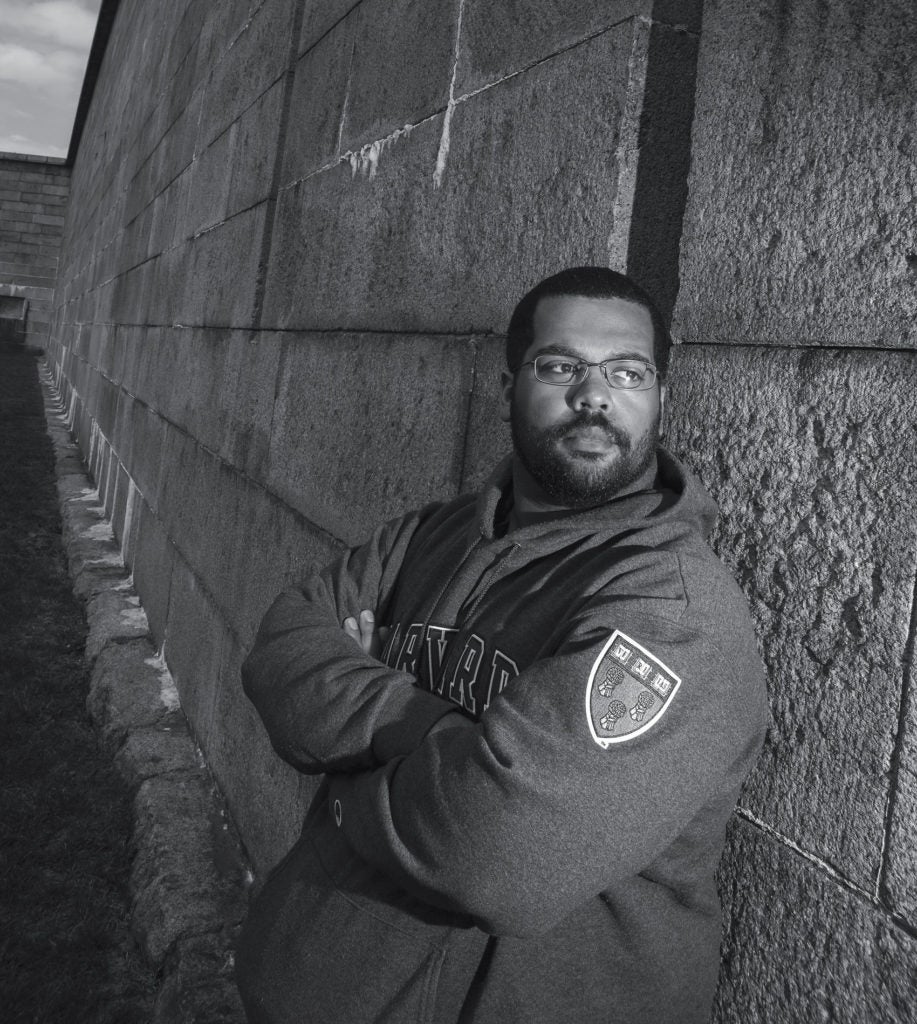

When Jin Kim ’18 was 13, his family emigrated from Seoul, South Korea, and settled in Georgia, just months before the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks: “I was the only one in my family who spoke English, and when it came to immigration proceedings and paperwork, even as a middle school student, I had to deal with all that. I remember a sense of hopelessness because of the nation’s fear of us.”

“The work we do may seem like it doesn’t impact everyday U.S. citizens, but some aspect of their lives has been or will be touched by immigration law. Before the executive orders I think people overlooked immigration, but at some point in their family history, because of how this country was founded, we’ve all been impacted by the immigration system.”

Kim understands what it’s like to undergo vetting by the Department of Homeland Security and to be left in limbo. “I remember calling the immigration hotline to inquire about the status of my family’s application after my grandfather passed away in Korea,” he says, “and it was like the answer was, ‘You just have to wait and see.’” They waited, but the application process was so delayed after the 9/11 attacks, they couldn’t leave the United States to attend the funeral.

He believes his experience helps him understand what immigrants are going through now: “You don’t know what executive order is going to come out tomorrow. We’re at that point in time where immigrants don’t really know what’s going to happen to their lives. It brings a sense of hopelessness.”

Kim wasn’t surprised when the first executive order was signed—HIRC was already working on a way to unravel the travel ban. “Sabi Ardalan [’02, assistant director of HIRC and assistant clinical professor of law] was able to get a copy of the first order, a few days before it came out, through the distribution list of immigration professors and lawyers. She gave me a copy and I started reading it, so we could find a way to challenge it.”

He helped with an amicus brief supporting one of the legal challenges. He also contributed to a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for an emergency hearing on the Trump executive orders. By the spring, he was enrolled in the clinic, working on several asylum cases. When the hearing was granted, he and another HIRC student traveled to Washington to testify in front of the commission.

Kim and Malene Alleyne LL.M. ’17 spoke in particular about the Safe Third Country Agreement, which allows Canada to turn away asylum seekers entering from the United States on the premise that the U.S. is a “safe country of asylum,” a premise which the clinic argues is now false. They also described the climate of fear generated by the Trump executive orders and testified that their clients don’t feel they can leave their houses for fear they will be taken into custody and deported.

When Mana Azarmi ’17 decided to attend law school, she chose Harvard because of the scale and breadth of topics covered in its clinical programs, and the institution’s willingness to devote resources to programs that are in the public interest.

“Having clinical instructors like Sabi Ardalan and Phil Torrey and seeing how they interact with clients, watching the amount of respect they have for everyone and how patient they are – they’re phenomenal people to learn how to be a lawyer from.”

The daughter of Iranian immigrants, Azarmi is interested in shielding minority communities from government encroachment on their civil liberties. Her studies have tied together immigrant rights and privacy law, with a particular emphasis on surveillance practices. “In times of national crisis, [these] are two areas of law that are ripe for abuse,” she states. Azarmi is interested in everything from how ICE monitors immigrant communities to what they do with data collected from surveillance.

She has also focused on the unregulated activities of data brokers, companies that aggregate information about individuals from their public records, social media and web browsing history. Brokers often sell data like consumer purchase histories to advertising and marketing companies, but these middlemen can sell these data-aggregated profiles to government agencies, circumventing potential First Amendment violations and undermining constitutional protections against unlawful searches. These agencies may use this questionable data to flag people as terrorists or affiliated with terror groups. “That may delay their applications for years, and they won’t be informed why,” she says.

Azarmi has completed two semesters of clinical study at HIRC, with a focus on the area of “crimmigration”—at the intersection of criminal law and immigration law. Her work was guided by Lecturer on Law Phil Torrey, HIRC’s managing attorney, who filed an amicus brief this spring in Commonwealth v. Sreynuon Lunn, on the question of whether Massachusetts police can detain and arrest someone for a U.S. immigration violation.

This semester, she has helped with the briefs submitted by HIRC, including the one in support of International Refugee Assistance Project v. Trump. According to the brief, the cap on refugees would violate the Refugee Act of 1980. While studying for the bar exam, Azarmi will pursue work related to her interest in privacy and surveillance practices that impact immigrant communities. “Things aren’t going to get better for immigrants until people demand that things get better for immigrants,” she says.