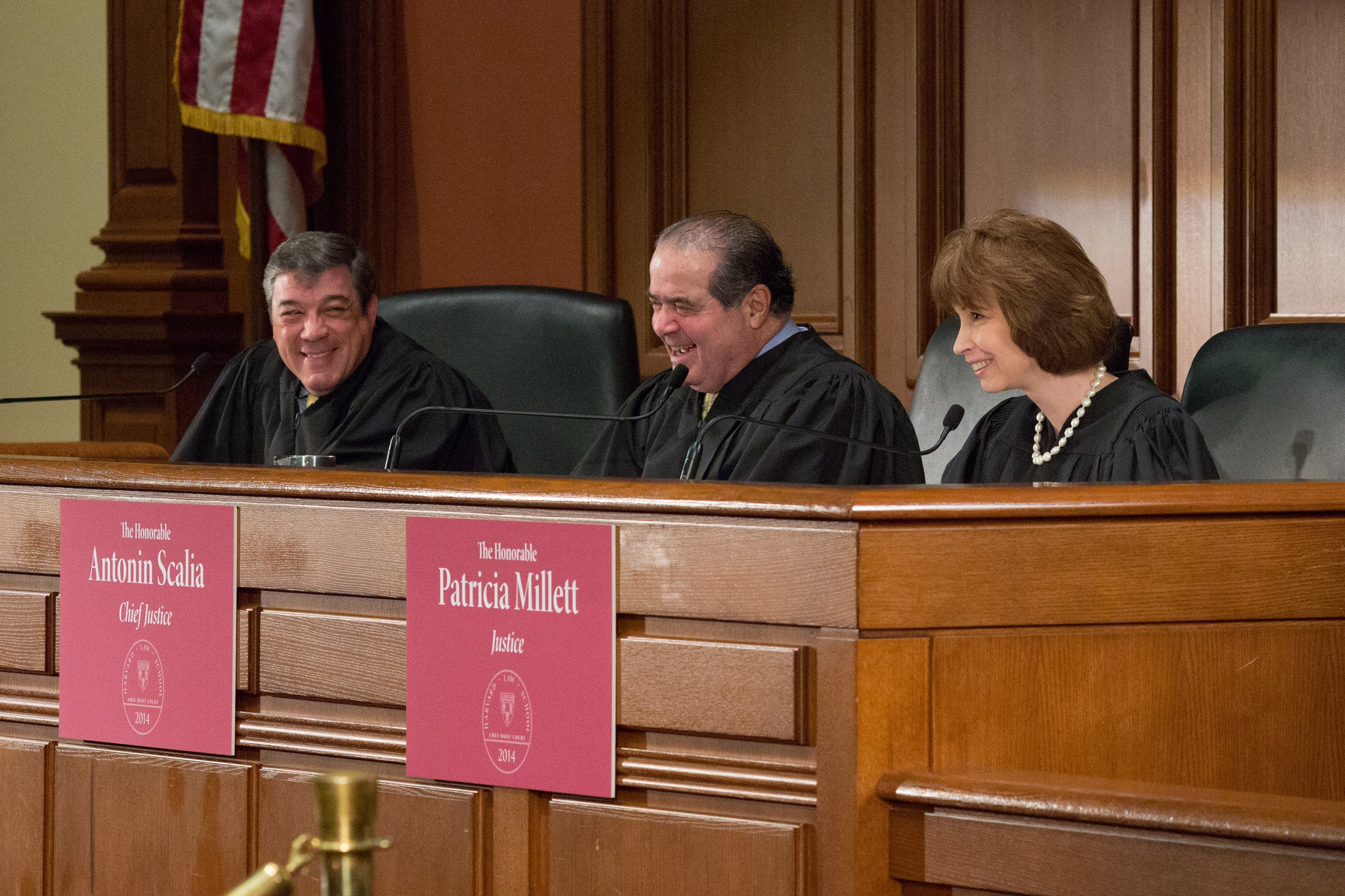

Third-year Harvard Law School students clashed in the high drama of the venerable Ames Moot Court Competition on Tuesday under the jurisdiction of visiting federal judges, including one of the nation’s foremost legal authorities, U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia.

“It was fully as good as one would expect at Harvard Law School,” a pleased Scalia said during his final comments.

During the arguments, Scalia flashed his famed wit, drawing laughter as he questioned teams of students arguing the merits of letting a career criminal appeal his conviction on a drug charge.

Scalia, LL.B. ’60 and a Sheldon Fellow ’60-’61, was joined on the bench by Judge Adalberto Jordan of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit; and Judge Patricia Millett, ’88, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

The justices directed blunt questions toward the two teams, but the students stood their ground in defense of their arguments, which impressed the judges. “This is as good an argument as you are likely to hear in a court of appeals, and probably in my court,” Scalia said after deliberations.

The judges didn’t render a decision, but named Kevin Neylan the best oralist, awarded the petitioning team the best-brief award, and named the respondents the best overall team.

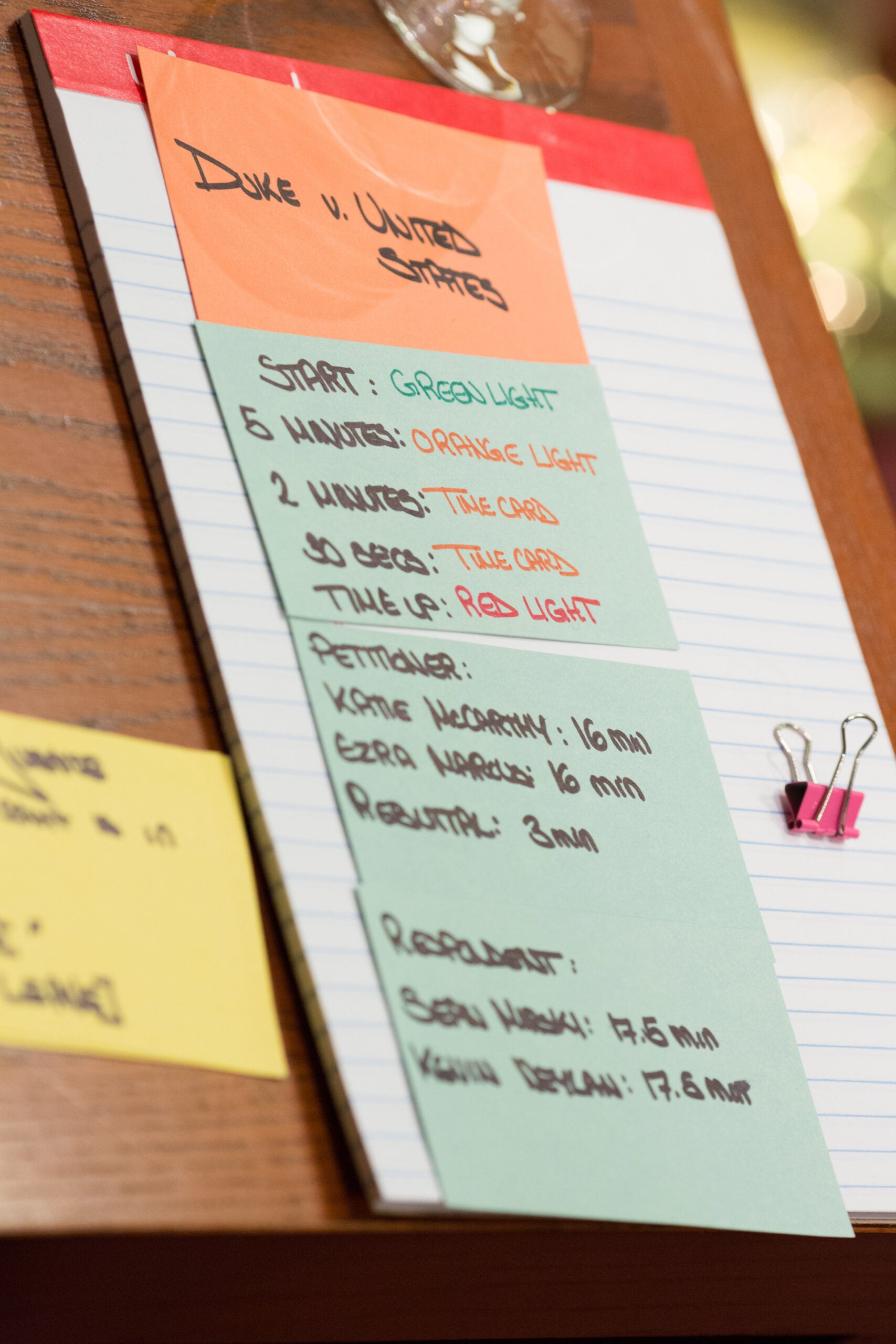

The petitioner’s team was made up of Jennifer Garnett, Jordan Moran, Ivan Panchenko, and Tom Ryan, along with oralists Ezra Marcus and Katie McCarthy.

The respondent’s team was made up of Jay Cohen, Cody Gray, Spencer Haught, and Christina Martinez, along with oralists Sean Mirski and Neylan.

Each oralist faced the panel of judges for 16 minutes, followed by a three-minute rebuttal by Marcus.

Scalia’s moot court heard a request for an appeal in the case of a “defendant” who was convicted of possession of crack cocaine with intent to distribute, after a plea deal in which the charge of possessing a firearm in connection with drug trafficking was dropped with the stipulation he wouldn’t appeal his sentence.

The trial judge had followed guidelines for career criminals and imposed a stiffer sentence on the defendant who had two prior felony controlled-substance convictions.

After his conviction, the defendant demanded his attorney appeal the conviction, claiming the trial judge erroneously ruled the defendant played more than a minor role in the crime. The attorney refused because the defendant waived the right to appeal and appealing would break the plea deal, which would open him to an even harsher sentence.

There were curves thrown at the students. Shortly after the conviction, the circuit court in which the district court resided revised its own rules for considering what makes a career criminal, which would have changed the defendant’s status. The petitioning team argued the defendant had received inadequate legal counsel when the defense attorney refused to file a notice of plans to appeal, and it challenged the sentencing based on the change in law. The responding team defended the sentencing based on the plea agreement and interpretation of the law at the time of the trial.

Relief from the tension seemed to explode through the courtroom when the justices left to deliberate. The teams hugged, shook hands, and slapped each other on the backs as the capacity crowd gave them a boisterous, prolonged standing ovation.

“I think that for most of us, it was the defining experience of law school, and the experience of working with a team is what makes it worthwhile,” Marcus said. “That’s the real world in practicing law.”

It was a difficult case to argue, but the students rose to the occasion, Jordan said. He had questioned students at length on their arguments and reasoning, challenging their memory of case law during their briefs, and then called it an honor to sit on the bench during presentations.

“You guys did a good job finding where the gaps were, where the problems were,” Jordan said.

Millett was effusive in her praise of the students. The teams were engaged in their work and used case law as well as it could be done, she said. “These were two spectacular sets of briefs; I wish I got briefs like this every day,” Millett said. “These were four spectacular oral arguments.”

It’s important for attorneys to establish a rapport with the bench when arguing a case, but some attorneys think questions from judges are an interference as they regurgitate their briefs, Scalia said. “Good advice for counsel is [to] welcome questions,” he said.

The moot court has been held since 1911. The competition starts with a qualifying round for second-year students who develop briefs on hypothetical cases that are presented in moot courts with fellow students, teachers, and attorneys acting as judges. The final four teams then argue another case with real judges before the last two teams move to the Ames Court.

This article was originally published on November 20, 2014 in the Harvard Gazette Online.

***

The 2014 Ames Moot Court Competition, in brief

The final round of Harvard Law School’s 2014 Ames Moot Court Competition took place on Nov. 18 in Ames Courtroom, Austin Hall.

The Hon. Antonin Scalia ’60, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, the Hon. Adalberto Jordan, U.S. Court of Appeals Eleventh Circuit, and the Hon. Patricia Millett ’88, U.S. Court of Appeals District of Columbia Circuit, presided over this year’s competition, in which two teams of 3L students presented arguments in the fictional case of Duke v. United States (case details below). This year’s teams were:

The Franklin E. Kameny Memorial Team, Petitioner.

- Jennifer Garnett ’15;

- Ezra Marcus ’15, oralist;

- Katie McCarthy ’15, oralist;

- Jordan Moran ’15;

- Ivan Panchenko ’15; and

- Tom Ryan ’15.

The petitioner’s team was named after the late Dr. Frank Kameny, an astronomer for the U.S. Army Map Service, who filed the first civil rights claim based on sexual orientation. Kameny was fired in 1957 when the Civil Service Commission discovered he was gay. He appealed his termination, writing the petition that brought the first gay rights claim ever filed with the Supreme Court, in 1961

The Elliot L. Richardson Memorial Team, Respondent.

- Jay Cohen ’15;

- Cody Gray ’15;

- Spencer Haught ’15;

- Christina Martinez ’15;

- Sean Mirski ’15, oralist; and

- Kevin Neylan ’15, oralist.

The respondent’s team was named after Elliot Richardson ’47 who devoted his career to public service. Richardson served as head of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare from 1970 to 1973 and briefly served as Secretary of Defense before being named U.S. Attorney General in May 1973. Richardson resigned in October 1973 during the Watergate scandal rather than obey President Nixon’s order to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox.

The Elliot L. Richardson Memorial Team won best overall team this year. The petitioner, the Franklin E. Kameny Memorial team, won Best Brief. The award for Best Oralist went to Kevin Neylan, a member of the Elliot L. Richardson Memorial Team.

The following is a brief description of the 2014 Ames Moot Court Case Duke v. United States, including Final Round Record and Briefs:

A federal grand jury returned an indictment charging Jaden Duke with possession with intent to distribute crack cocaine, and possession of a firearm in connection with drug trafficking. The government agreed to drop the gun charge if Duke pled guilty to the drug offense. The plea agreement acknowledged that Duke might be sentenced harshly as a career offender under § 4B1.1 of the United States Sentencing Guidelines—an enhancement that applies when a defendant has two prior felony controlled substance convictions. The agreement also included an appeal waiver that bars Duke from appealing his conviction or his sentence.

The district court sentenced Duke to 262 months in prison. The court determined that Duke’s two prior drug offenses were each punishable by more than one year in prison, and therefore constituted predicate controlled substance felonies that warranted a career-offender sentencing enhancement raising Duke’s advisory sentencing range from 155 – 188 months to 262 – 367 months. The court did not find that Duke played a mitigating role in the offense—a finding that would have reduced his sentencing range by a little bit.

After he was sentenced, Duke demanded that his attorney, Milton Fountain, file a notice of appeal in order to challenge the district court’s conclusion that he did not play a mitigating role in the offense. But, Fountain reasoned that an appeal would be frivolous in light of the appeal waiver in the plea agreement; he further noted that if Duke breached the agreement by appealing, he would permit the government to reinstate the firearm charge. Fountain thus refused to appeal despite Duke’s contrary instruction. Duke’s sentence became final in November 2009.

Nine months later, the Ames Circuit revised its methodology for determining whether prior offenses qualify as predicates for career-offender sentencing. Prior to United States v. Sanchez, — F.3d — (Ames Cir. Sept. 8, 2010), courts in the Ames Circuit, including the district court in Duke’s case, assessed the gravity of prior offenses by determining whether a hypothetical defendant with the worst possible criminal history could have received more than one year for the offense. In Sanchez, the Ames Circuit changed course, holding that courts must consider the characteristics, including criminal history, of the actual defendant, as opposed to a hypothetical one. In Duke’s case, he was only eligible for 8 months’ imprisonment for his first drug offense. Thus, under Sanchez, that offense is not a qualifying controlled substance predicate offense, and Duke should not have been sentenced as a career offender.

Duke now challenges his sentence under the federal habeas corpus statute, 28 U.S.C. § 2255, which permits an inmate to argue that his “sentence was imposed in violation of the Constitution or laws of the United States, or that the court was without jurisdiction to impose such sentence, or that the sentence was in excess of the maximum authorized by law, or is otherwise subject to collateral attack.” The lower courts ruled in the government’s favor, and Duke petitioned for certiorari. The two questions presented for the Court’s review, both of which are the subject of circuit splits, are:

- Whether counsel renders ineffective assistance in violation of the Sixth Amendment by failing to file a notice of appeal at a defendant’s request when the defendant has waived his right to appeal in a plea agreement.

- Whether a prisoner may challenge his sentence under 28 U.S.C. § 2255 when an intervening change in law demonstrates that the prisoner was erroneously sentenced as a career offender.

The Final Round Record and Briefs

Duke v. United States – Record