“People tend to think that only bad people go to prison.”

“Freedom is the most beautiful thing life has to offer.”

“I am not a criminal I was a drug addict.”

“Beautiful things are never perfect.”

Those words, written by formerly incarcerated women, are just a few of the many thought-provoking and provocative statements included in an interactive new exhibition in Lawrence, Kansas called “How the Light Gets In,” created by Sarah Newman and metaLAB (at) Harvard, in collaboration with the KU Center for Digital Inclusion.

The multisite installation features the sentiments of dozens of formerly incarcerated women and explores themes such as compassion, curiosity, technology, knowledge-sharing, and criminal justice reform, says Newman. The installations also invite visitors to contribute – and take home – pieces of wisdom, adds Newman, who is Director of Art and Education for metaLAB (at) Harvard, part of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society.

“Everyone struggles, everyone learns, everyone has something to teach,” says Newman. “More than anything, most of these women were unlucky. Many of them were victims who society has continued to punish and victimize. The premise of this exhibition is that everyone can be a teacher, so we wanted to create a platform where knowledge among strangers can be shared and redistributed by the artwork itself.”

The exhibition, which recently opened at the Spencer Museum of Art and Lawrence Public Library sprang from the work of Hyunjin Seo, director of the Center for Digital Inclusion at the University of Kansas, whom Newman met when they were both Berkman Klein fellows. Along with Seo’s work at the Center for Digital Inclusion, which promotes digital literacy and access to underserved populations, she is also the Oscar Stauffer Professor at the University of Kansas.

Starting in 2020, thanks to a grant from the National Science Foundation, the KU Center for Digital Inclusion has worked with hundreds of formerly incarcerated women to break down barriers they face to reentry and to build their skillsets. “The Center for Digital Inclusion uses a co-design principle in developing our technology education curriculum while centering participants’ interests and needs,” says Seo.

At the same time, Seo and her team have learned from the women about the biases they face and about their resilience in reentry, she says. “And based on these insights from our participants, we wanted to use an art form to facilitate dialogue around structural barriers and societal biases facing justice-impacted women and to learn from their wisdom and resilience.”

Seo reconnected with Newman, who was keen to explore the topic. “Experience is the best teacher, after all, and these women have plenty of it,” says Newman, adding that the goal of their exhibition is “to invert the traditional narrative of who can be teachers in society, who has wisdom to share, and provide a reminder of the value of learning from strangers, and treating everyone with compassion and dignity.”

Seo and Newman, along with Joey Orr, a curator at the Spencer Museum of Art, secured funding from the National Endowment for the Arts for the project, and 28 women from the technology education program agreed to participate.

“The premise of this exhibition is that everyone can be a teacher, so we wanted to create a platform where knowledge among strangers can be shared and redistributed by the artwork itself.”

Sarah Newman, co-creator of “How the Light Gets In”

Over the following months, Newman held workshops, activities, and one-on-one conversations with the participants, who shared their responses to a variety of prompts such as “What is something you learned as a child that serves you to this day?” “What misconceptions to people have about incarceration?” “What advice would you give to your younger self?” Their answers, which explored their lives, wisdom, and experiences, shaped the exhibition.

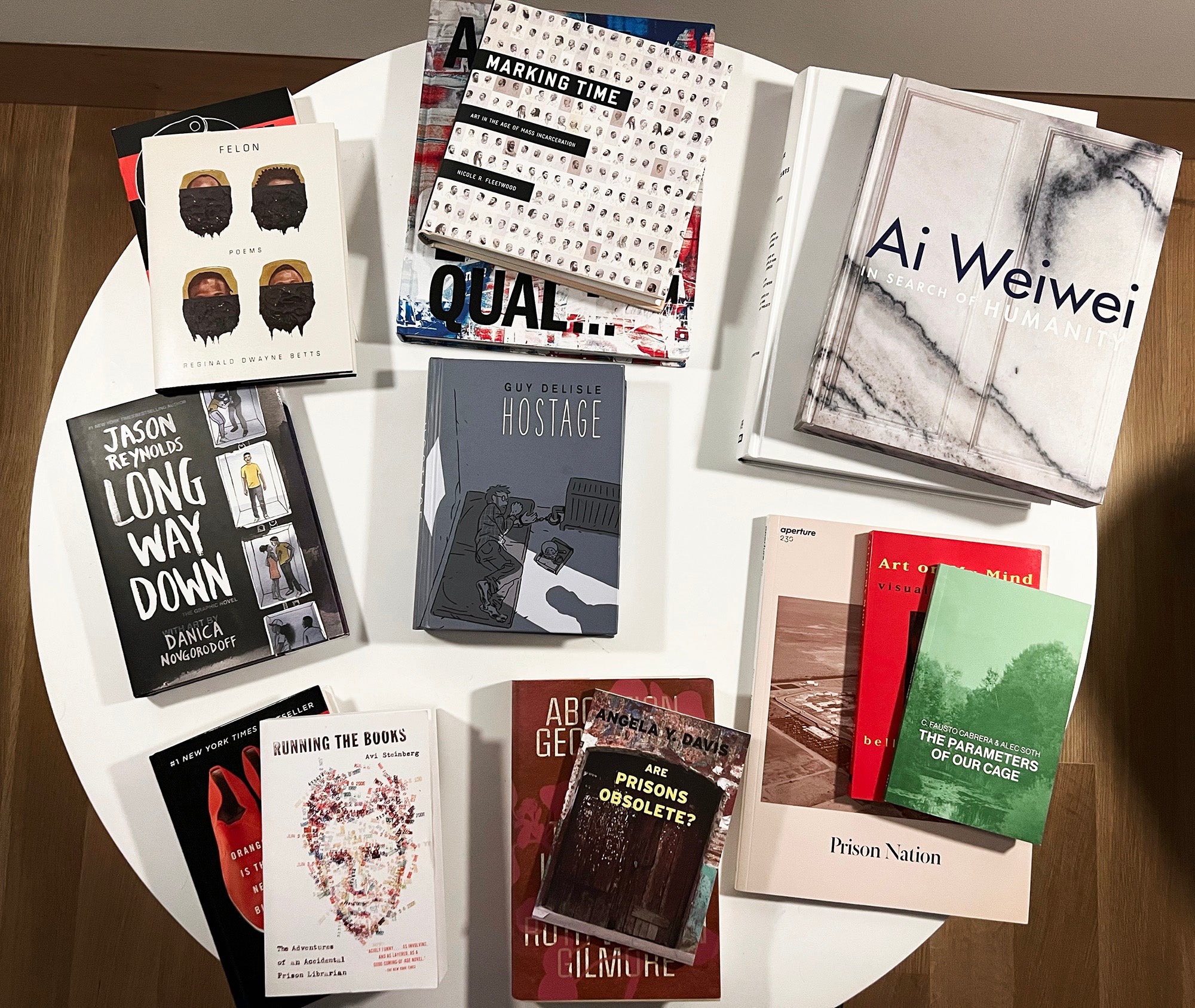

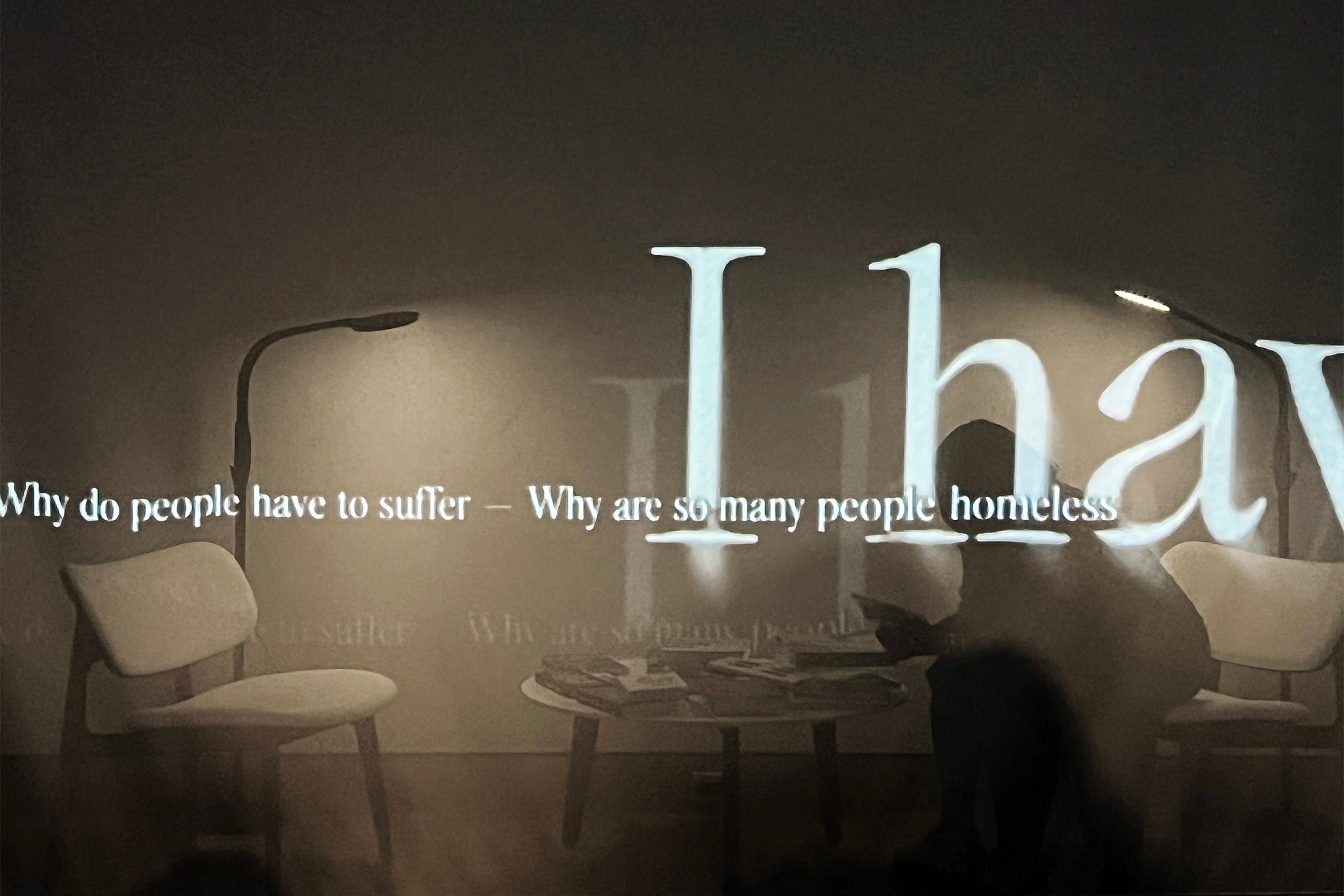

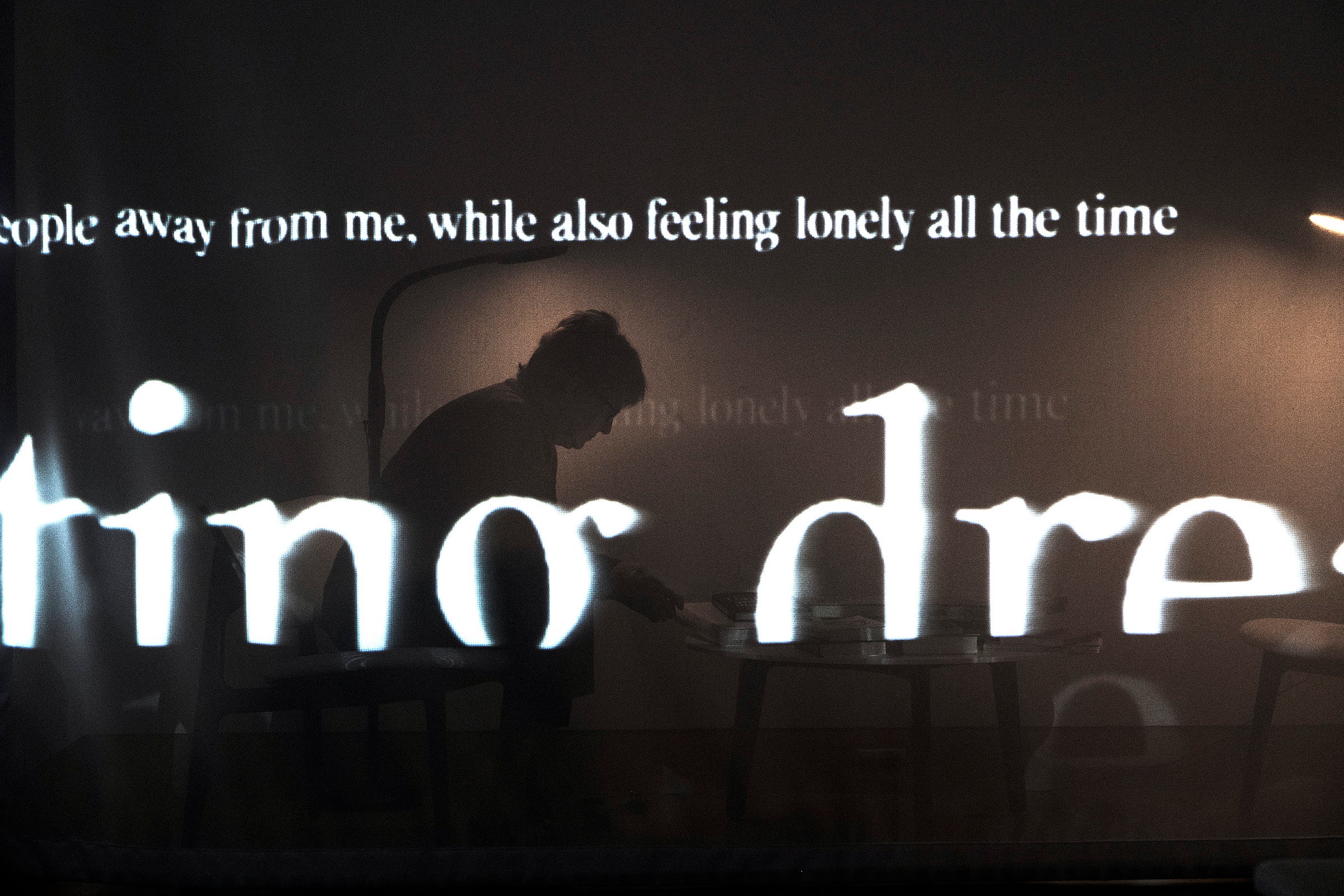

Newman and her team at metaLAB then designed two complementary site-specific works at the Spencer Museum and the Lawrence Public Library. At the museum, the installation is a darkened gallery, with immersive 360 degree projection of the women’s insights in a dreamlike, ethereal style. The gallery also contains six “alcoves” created with theater scrim, where museum-goers can submit their own wisdom to this growing collection via laptops with nine questions that cycle through, or visit the one alcove that serves as a reading nook and provides a selection of books that Newman chose to complement the exhibition and connect it to the broader selection of books at the library.

The centerpiece of the museum installation features small pieces of paper that slowly drop from the ceiling from several receipt printers that are mounted in the ceiling. The prints contain advice and wisdom from the women participants combined with the submissions of museum and library goers throughout the duration of the exhibition. Visitors may catch these as they are falling, explore the pile that grows in the center of the gallery, and if they’d like, they are welcome to collect them and take them home, says Newman. The museum installation also includes an audio composition by metaLAB affiliate Halsey Burgund.

“By using the wisdom of the women on the walls, and mixing in the words of the museum and library visitors into the printouts, we hope the show can honor the women and the unique difficulties they face with reentry and the specific wisdom they have, while also acknowledging everyone in their individual perspectives, struggles, and insights,” Newman adds.

At the library, which is located in downtown Lawrence, the installation includes a custom light installation, eight quotes from the women on the columns that surround the atrium, and a selection of books about justice, oppression, and freedom that were selected by the librarians and placed in a temporary reading area in the middle of the atrium. There is also a tablet and printer where library patrons are invited to contribute their own words of wisdom, and collect printouts from the printer.

“Libraries are traditionally a space that embraces knowledge, learning, free exchange of information, and the entirety of lived experience, so when I first spoke with Newman about hosting How the Light Gets In at Lawrence Public Library, conceptually the project felt like a perfect fit,” says Heather Kearns of the Lawrence Public Library. “It wasn’t until we were installing the work that it suddenly felt very human and critical. It was the scale and seeing ‘I’m not a criminal I was a drug addict’ spanning 20 vertical feet in our most central crossroad space that made me think how we’re literally making it impossible to ignore these voices.”

Kearns adds that libraries are one of the last free places open to everyone, including those experiencing homelessness, addiction, or mental health challenges. “We see people at their best and in crisis. When you’re here, it’s hard to ignore what’s happening in your community. Libraries keep communities connected physically and emotionally in an increasingly distracted and fractured world. This exhibition is just the sort of conversation that needs to be happening. It’s hard to ignore and I believe that’s a good thing.”

The show has already drawn interest and praise from community members and from the participants themselves. “Many of the women whose words are featured in the exhibition were at the opening a few weeks ago, and they loved it,” says Newman. “They said it surpassed their expectations, and that working with us on this project was incredibly positive for them. There were many happy tears as they saw their words and reflections projected on the walls of the museum, and their names acknowledged on the wall text.”

Newman says she hopes the exhibition will prompt visitors to think critically about and get involved with reforming the criminal justice system, including making it more rehabilitative, and prioritizing treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders. She wants visitors to come away with more compassion and humility. “I hope to encourage a general curiosity about strangers, and a realization that we can all be teachers, and we all have something to learn,” she says.

Newman credits additional Harvard affiliates, including Juliana Castro, a BKC fellow, along with Daniel Feist (MDE), Sabrina Madera (GSD), Sonia Ralston (GSD), and Jade Wu (MDE) with their work on the exhibition, which will run through January 2023.