To save a culture of cold, lawyers turn up the heat

Climate change may still be a distant threat for many Americans, but here in Alaska, the effects are inescapable.

Houses, roads and airports buckle because the permafrost is no longer permanent. Native villages are swept out to sea because the ocean ice, which has protected them from violent storms since humans first crossed the Bering Strait, has receded offshore. And polar bears—the most visible symbols of our nation’s arctic environment—are drowning. In fact, since 1979, 20 percent of the Arctic sea ice has melted—an area twice the size of Texas. That’s why a dedicated contingent of Harvard-trained lawyers has made Alaska its frontline, contending that, if left unchecked, the environmental disasters in the nation’s 49th state will soon wreak havoc on the lower 48. “We are the canary in the coal mine,” said Deborah Williams ’78. “Everything that’s happening in Alaska right now has local, national and international implications.” On the most local level, Heather Kendall-Miller ’91 and Luke Cole ’89 have filed a landmark suit against 24 energy companies on behalf of the Native Alaskan village of Kivalina, which lies 80 miles north of the Arctic Circle on the Chukchi Sea. In Kivalina v. Exxon, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, they claim the defendants produce greenhouse gases that have melted the protective barrier of sea ice that shields the village from fierce autumn storms. They seek damages for the estimated $400 million it will cost to relocate the village.

Portage glacier, a popular tourist attraction that once dominated this bay near Anchorage, has receded and is no longer visible from the visitors center.

Meanwhile, Williams is leading the charge on the political and educational fronts. As founder and president of Alaska Conservation Solutions, she has made it her mission to convince senators, governors and federal regulators to rein in the emission of greenhouse gases. As part of her lobbying efforts, she brings key decision-makers to Alaska to see what atmospheric warming can do. “Seeing is believing,” she said. “We are helping leaders in other parts of the country make the connection between what is happening in Alaska and what will happen in their state.”

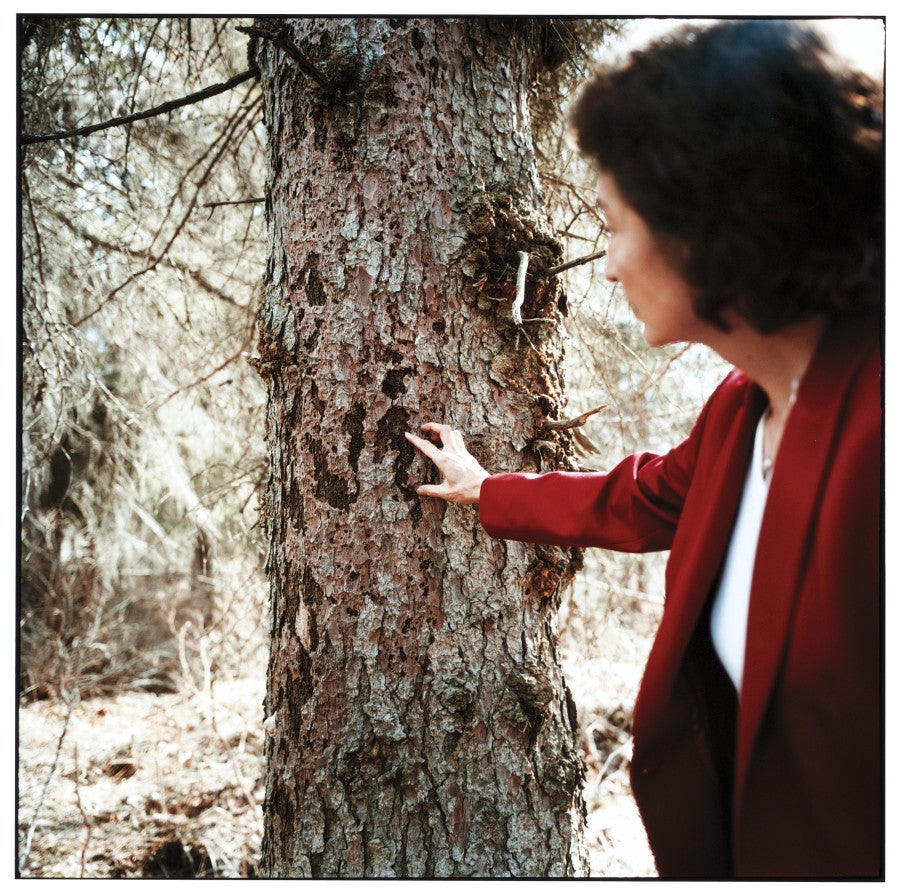

Williams points out the towering peaks that rise from the ocean three miles across Turnagain Arm just south of Anchorage. A swath of dead spruce trees forms a brown belt around the base of one of the mountains. “Spruce bark beetle,” she said. With just a 4-degree rise in the average temperature over the last two decades, she explains, the beetles are thriving and the trees dying en masse. That strip of brown is just the northern edge of a massive blight that has swept through the Kenai Peninsula, a breathtaking tourist Mecca of glaciers, fjords and mountain meadows. “Four million acres of white spruce have been wiped out so far,” said Williams. That’s an area nearly twice the size of Yellowstone Park.

And the damage is no longer confined to Alaska. As Williams tells her visitors, similar pests such as the pine bark beetle are now destroying forests in Montana, Idaho, California and Arizona. Williams takes people to see the site of Portage Glacier about an hour’s drive from Anchorage—or the former site, that is. In 1985, the state built a multimillion-dollar visitors center to view the glacier, but all that can be seen from the center now is a lake. The glacier itself has retreated behind a mountain ridge two miles away. “Every square inch of white we lose amplifies the speed of global warming because when solar radiation hits white, it’s reflected, but when it hits blue or brown, it is absorbed,” said Williams. “We are losing one of the most endangered critical habitats in the world. Everyone understands the seriousness of destroying the rain forests. But the Arctic is just as functionally important to the global environment as the rain forest.” On the litigation front, Kendall-Miller has joined the battle against climate change because of its impact on Native Alaskans, whom she represents as a senior attorney for the Native American Rights Fund. She argues, quite passionately, that rising temperatures are wiping out a subsistence culture that has existed for 4,000 years—and that the loss of that unique way of life would leave us all impoverished.

She says that for many Americans, the term subsistence may be a synonym for marginal or primitive. But to the Athabascan, Aleut, Tlingit, Yup’ik and Inupiaq peoples, it is shorthand for a complex set of beliefs that are inextricably linked to the land and water around them. “They have a distinct worldview—a unique relationship with each other, the natural world and the spiritual world,” she said. “The biggest challenge for me, as their lawyer and advocate, is to express to the general public the integrity of that difference.” To do that, Kendall-Miller gathered testimony from Native Alaskans. In a series of hearings around the state, they described how climate change has driven caribou from traditional hunting grounds; melted the ice required for the survival of seals, walrus and polar bears; and caused a dramatic increase in diseased salmon as rising river temperatures threaten the spawning grounds for one of the most productive fisheries on the planet. “It’s scary,” said Oscar Kawagley, a Yup’ik Indian from Bethel, Alaska. “Cold is what makes my language, my culture, my identity. What am I going to do without cold?”

In spite of their passion and legal expertise, Kendall-Miller and Cole (who is the director of the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment in San Francisco) lacked the resources needed to take on 24 of the largest energy companies in the world. So they pulled together a team of six top litigation firms from around the country. Taking a page from the tobacco litigation playbook, they sued the energy companies on a public nuisance theory. They also alleged conspiracy, arguing that, like the tobacco industry, the energy companies worked in concert to promote false science that cast doubt on the reality of global warming. Although the plaintiffs have some significant hurdles, their success would have an “enormous impact,” according to Roger Ballentine ’88, president of Green Strategies in Washington, D.C., and a visiting professor at HLS. “A suit like this faces a number of challenges,” said Ballentine. There is the question of whether a federal common-law claim is available in a global-warming suit and whether courts will continue to deny jurisdiction on the grounds that Congress, not the courts, is the proper forum for resolving these issues. “Causation could also be a significant problem,” Ballentine added. “But if they were to succeed in making a link between greenhouse gas emissions and the damages the plaintiffs have suffered, it would open the floodgates for climate-change suits.”

[pull-content content=”

The Snowy Trek

Heather Kendall-Miller ’91 took a winding road to Harvard Law School—and there were grizzlies and caribou along the way.

Kendall-Miller’s mother, a full-blooded Athabascan, met her father when he returned to Alaska after being stationed in the Aleutian Islands during World War II. But she died when her daughter was 2, cutting her off from her native roots.

Raised in Fairbanks, Kendall-Miller dropped out of high school and went to work on the Alaska Pipeline, homesteading in a remote valley in the mountains north of the Yukon River. At 17, she married, and she and her husband built a cabin on the land, heated it with water they piped in from a hot spring a quarter mile away.

“I look back fondly on those years,” Kendall-Miller recalls. “We were dropped off in the middle of nowhere and built our cabin in a beautiful valley in the Ray Mountains. It was a wonderful, magical place surrounded by grizzlies and caribou and moose. We had to fly in by float plane, air-drop our supplies over the cabin, and then land on a lake seven miles away and hike back to the cabin.”

Kendall-Miller became pregnant when she was 21 and lived in the cabin for another two years until her marriage collapsed. A single mother working construction on the Alaska Pipeline, she realized that her daughter needed a more stable life.

So at age 25, she enrolled at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, where she developed an interest in Native American rights. She graduated magna cum laude and, based on the recommendation of a professor, applied to Harvard Law School.

“I knew all along that I wanted to come back to practice in Alaska,” she says. “It was exciting to be around all these incredibly smart people who were so purposeful. I knew Harvard would give me the credentials I needed to focus my career the way I wanted to and help Native Alaskans when I got back.”