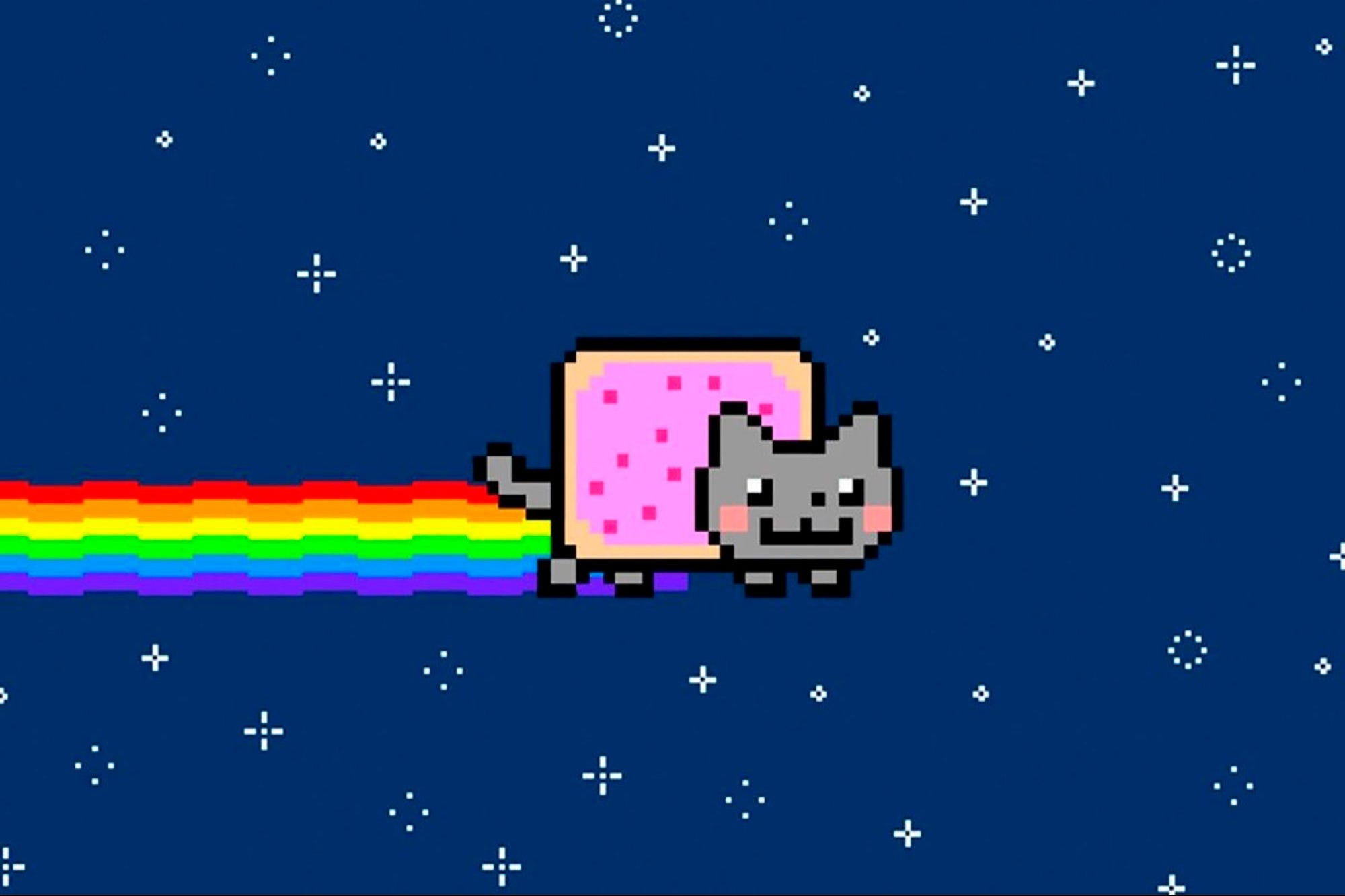

While art has always been in the eye of the beholder, skeptics might debate the merits of spending more than a half a million dollars to buy a digital meme of a cartoon cat with a pop tart body flying through space leaving a trail of rainbows in its wake.

The “Nyan Cat” is just one example of an NFT, or non-fungible token, the latest realm for aficionados to secure one-of-kind collectibles. NFTs can be any type of data — memes, tweets, or digital creations — which are recorded and sold on the blockchain and certified to be unique.

When you purchase a painting, you have a tangible item to call your own. When you purchase an NFT, all you have is the privilege of having your ownership recorded on the blockchain – a process so energy-intensive that it is contributing to climate change, according to many environmentalists.

Despite these shortcomings, the high-priced sales of creative NFTs have recently become ubiquitous. Harvard Law Today asked intellectual property law expert Rebecca Tushnet, Frank Stanton Professor of the First Amendment, to help make sense of the NFT boom.

Harvard Law Today: What are your thoughts about creative NFTs and what do you think accounts for their recent surge in popularity and public awareness?

In lockdown, people can’t do many of the things they usually do for fun, so they trade intangibles instead

Rebecca Tushnet: Matt Levine has what he calls the “Boredom Markets Hypothesis”: In lockdown, people can’t do many of the things they usually do for fun, so they trade intangibles instead. That seems like a good explanation for the rise of NFTs, with a side order of conspicuous consumption: instead of setting piles of money on fire, you can set piles of money on fire on the blockchain. And, of course, there is always some art that is about pushing boundaries, both of what counts as art and of what counts as a reasonable thing for a person to do.

HLT: Can you speak to the concerns scientists have raised about blockchain’s impact on the environment, and what these issues portend for the future of NFTs in the art space?

Tushnet: I don’t claim to be an environmental expert, but I have read persuasive critiques of the environmental impact of this method of measuring and recording wealth, and I suspect that more artists and collectors will be looking for ways to keep the money with less environmental impact, some through sincere desire to minimize harm.

Rebecca Tushnet, Frank Stanton Professor of the First Amendment

HLT: We’ve seen high-profile, large money transactions of digital art recently. As this monetization of digital creative IP increases, are existing IP laws and frameworks able to keep pace with the proliferation of these NFT transactions?

Tushnet: From an IP perspective, NFTs don’t change anything. If you didn’t have the rights to distribute a work before, you don’t have them now. If the sale or memorialization of an NFT involve reproducing and distributing a work that is under copyright—which they might not, at least for nonvisual works—then copyright will cover those reproductions unless a limitation or exception like fair use applies. Adding an NFT won’t increase anyone’s rights, whether over the Mona Lisa or the Brooklyn Bridge (which has already been made subject to an NFT or two).

HLT: When purchasing an NFT as a digital art collectible, what are you actually acquiring? Do you own the copyright to that material? Can you license an NFT that you’ve purchased for other commercial uses?

Tushnet: In one sense, the purchaser acquires whatever the art world thinks they have acquired. They definitely do not own the copyright to the underlying work unless it is explicitly transferred. Any licensing would have to happen separately, though if the copyright owner consented to the creation of the NFT there is probably at least an implicit license to make whatever copies are required for the ordinary operation of the NFT process.

HLT: What is the value of buying memes, such as the recent Disaster Girl sale, if the purchaser is not able to prevent other internet users from using a copy of that digital art file, or if the subject of the photograph still maintains rights to their likeness?

Tushnet: The value is the ability to say that you own the NFT. Like blockchain currency, it is worth whatever humanity collectively or individually decides it’s worth. It is a melding of Oscar Wilde and Andy Warhol, art for art’s sake and commerce for commerce’s sake.

HLT: More and more businesses are opting into this commercial space, but anyone can create an NFT to sell. Are there appropriate guardrails in place to ensure that users uploading their own creations are not violating any existing copyright?

Tushnet: The guardrails are the existing law: Copyright owners can sue over infringements, and they can also send DMCA takedown notices in appropriate circumstances if websites are hosting copies of their works in association with an NFT. However, many NFTs would not even implicate copyright rights. If I create and sell an NFT that I say is associated with the original manuscript of the next volume of the Game of Thrones series, I don’t have to own the manuscript or reproduce any part of it, and so no copyright right is implicated. In theory, there might be a trademark or false association claim, but if I explain my connection to George R.R. Martin—none at all—then that wouldn’t be a problem either.

This result comes because the only thing the blockchain can guarantee is its own chain of title. Once we jump to the physical world, possessing a token that says that I own X does not mean that I own the physical instantiation of X; I just possess the token. It is the rest of law and other human structures that determine whether that token has external validity.

HLT: With the speed at which the digital sector grows and changes, are there concerns that a digital asset you purchased could be rendered obsolete or inaccessible as the technology behind it ceases to be compatible with the future of operating systems?

Tushnet: Absolutely. Bit rot is real and we don’t have a history of preservation of these artifacts yet. That does not mean one couldn’t be developed, as they have been for other fragile media, but being digital doesn’t mean automatic transferability.

HLT: Do you see digital art collection as the future of the art world, or do you see this as a more temporary fad that will prove unsustainable long term?

Tushnet: I decline to speculate, because human behavior in practice regularly defeats the creative imagination.