It was a chilly afternoon outside the Allan B. Polunsky Unit, a maximum-security prison for death-row inmates in Livingston, Texas. Inside, the mood was somber. An execution was scheduled for later that day, and a sense of foreboding filled the air.

Law School student Jake Meiseles ’19, was talking to his client by phone through a thick glass window when he saw the condemned man walking behind the cubicle, followed by corrections officers. The man smiled and nodded at Meiseles, who did the same. The brief human exchange left Meiseles distraught.

“It was sad and upsetting,” said Meiseles, who was there as an intern with the Office of Capital and Forensic Writs in Austin, Texas. “But it kind of put into perspective the work we’re doing.

“It was like the worst-case scenario kind of looked me in the face, because if the work we’re doing fails, that’s the end.”

Meiseles was at the prison as a student in the Capital Punishment Clinic at Harvard Law School. Clinic students work remotely on the capital cases they began work on as interns with legal organizations around the country during J-term, interviewing witnesses, conducting field investigations, and drafting briefs, habeas petitions, and other motions. For Meiseles, meeting inmates on death row was memorable and deeply meaningful.

“Once you meet people who are facing the injustice that the death penalty is, that is something you can’t walk away from easily,” he said.

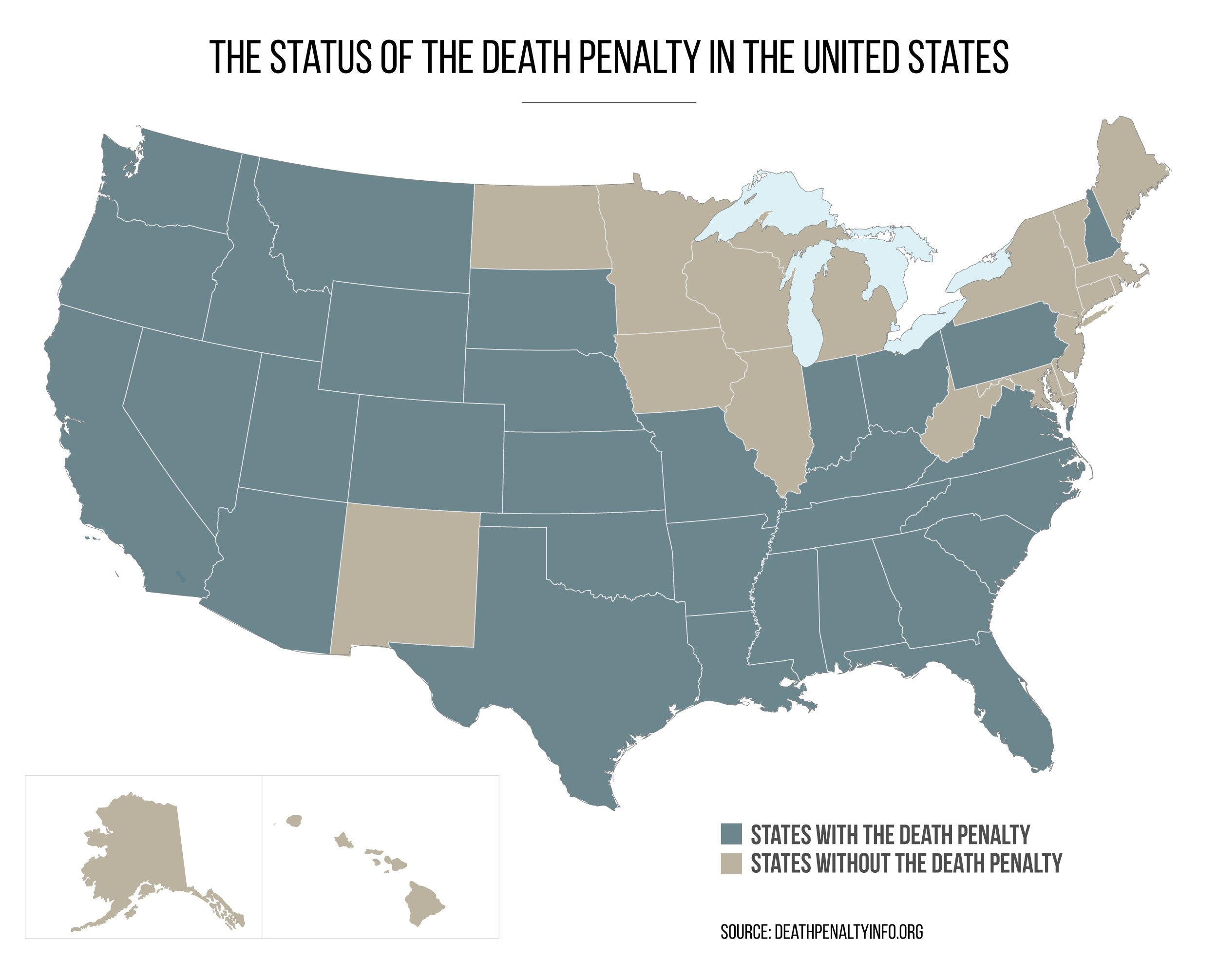

Led by Carol Steiker, the Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law and faculty co-director of the Criminal Justice Policy Program, the clinic tests the complex body of constitutional law that regulates the death penalty and its troubled history. The U.S. Supreme Court abolished the death penalty in 1972 but it was reinstated in 1976. The U.S. is the only Western democracy that carries out executions.

“The death penalty is a window into American history and the criminal justice system,” said Steiker, who was drawn to capital cases when she clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

“As a law clerk, you see the whole landscape of capital punishment in the U.S. laid out before you, and you see it’s concentrated substantially, almost exclusively, in the states of the former confederacy,” she said. “You see its roots in slavery, racism, and its current practice today reflects that.”

Nineteen states have abolished the death penalty. Of the 31 that retained it, 10 states have carried out executions since 2016, including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. But just 10 counties, in California, Texas, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Nevada and Florida, account for over a quarter of all recent death sentences in the country. Texas executes more prisoners than any other state.

Steiker’s “Capital Punishment in America” is a required course. After taking that and working in the clinic, many students end up questioning the death penalty’s effectiveness as a deterrent, which reflects the national attitude. Across the country, popular support for the death penalty is at its lowest point in four decades. Death sentences and executions have decreased, and that gives Steiker hope.

“The death penalty has fallen off the cliff in the last 10 or 15 years, in terms of its use and acceptability,” said Steiker. “It’s more fragile and questioned today than at any point in history since the 1960s. If you look at the states where the death penalty happens, you see a new fragility, one that, if it’s sustained, will lead to a new constitutional abolition.”

This fall, Steiker will be on leave. Her brother, Jordan Steiker, a law professor at the University of Texas School of Law, with whom she wrote “Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment,” will teach the course.

For Milo Inglehart, J.D. ’19, an internship with the Federal Community Defender Office in Philadelphia left him righteously indignant at how the death penalty is applied, comparing it to a legacy of lynching. Statistics show that 54 percent of death row inmates are black or Hispanic, and that they’re likelier to be sentenced to death when the victims are white.

“The main takeaways for me are first the overwhelming injustice of how the death penalty is meted out, and the importance of working to remedy that,” said Inglehart.

After interning with the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, Eliza McDuffie, J.D. ’19, felt such urgency that she’s contemplating a legal career in capital cases and or working in the South.

“I always knew the death penalty was really important,” said McDuffie, “but this experience solidified that for me. Not only is capital punishment wrong, but it’s not sustainable under the Constitution.”

Even when students don’t meet the prisoners they’re working to help, they still play a part in their legal representation. A snow storm canceled Caroline Darmody’s prison visit in New Orleans, but the 2019 J.D. candidate drafted an amicus brief for the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that her client was sentenced by a procedure that has been since held unconstitutional.

“The question was, while the procedures may have been constitutional at the time of his sentence, can we still sentence him to death?” Darmody said. “My brief argued that was a violation of the Sixth and the Eighth Amendments, and that he shouldn’t be executed today.”

On rare occasions, students meet prisoners who end up being executed. On average, inmates spend more than a decade on death row. Dana Or, J.D. ’18, met an inmate in the Polunsky Unit through her internship with the Texas Defender Service in Houston in January of last year. They met twice and in both occasions, they had a nice chat, she recalled.

“When we ended our last conversation, I told him that we weren’t going to say goodbye, that instead we were going to cross our fingers for his petition to stay his execution to be granted,” said Or. “This just shows how cruel this whole thing is.”

The clinic leaves students with a legal, social, and historical understanding of the death penalty, but what they say they remember most is the humanity of the prisoners, who are often portrayed as “beyond the pale of humanity,” said Steiker. Megan Barnes, J.D. ’19, recalled talks with inmates in which they exchanged childhood stories and chitchatted about the Kardashians.

“If more people would educate themselves about what’s truly happening in capital punishment in America, how fundamentally unfair and unjust is, it would be abolished tomorrow,” said Barnes. “If people understood that death row prisoners are not monsters, and that quite often they’re poor and lack adequate lawyers, there’d be calls for massive reforms.”

Steiker said that after grappling with the clinic’s weighty, life-or-death lessons, some students become capital defense lawyers, others work pro bono in capital cases, and many of those who don’t nonetheless become ardent opponents of the death penalty. Meiseles, whose interest in the death penalty goes back to his undergraduate years at Cornell University, plans to become involved in capital cases after his graduation.

“Many of the men sentenced to death ended up there due to prosecutorial misconduct, inadequate lawyers, and terrible racial undercurrents in the criminal justice system, and some are innocent,” he said. “It’s a terrible injustice that we as a society should not be tolerating.”

This article was originally published in the Harvard Gazette on September 5, 2018.