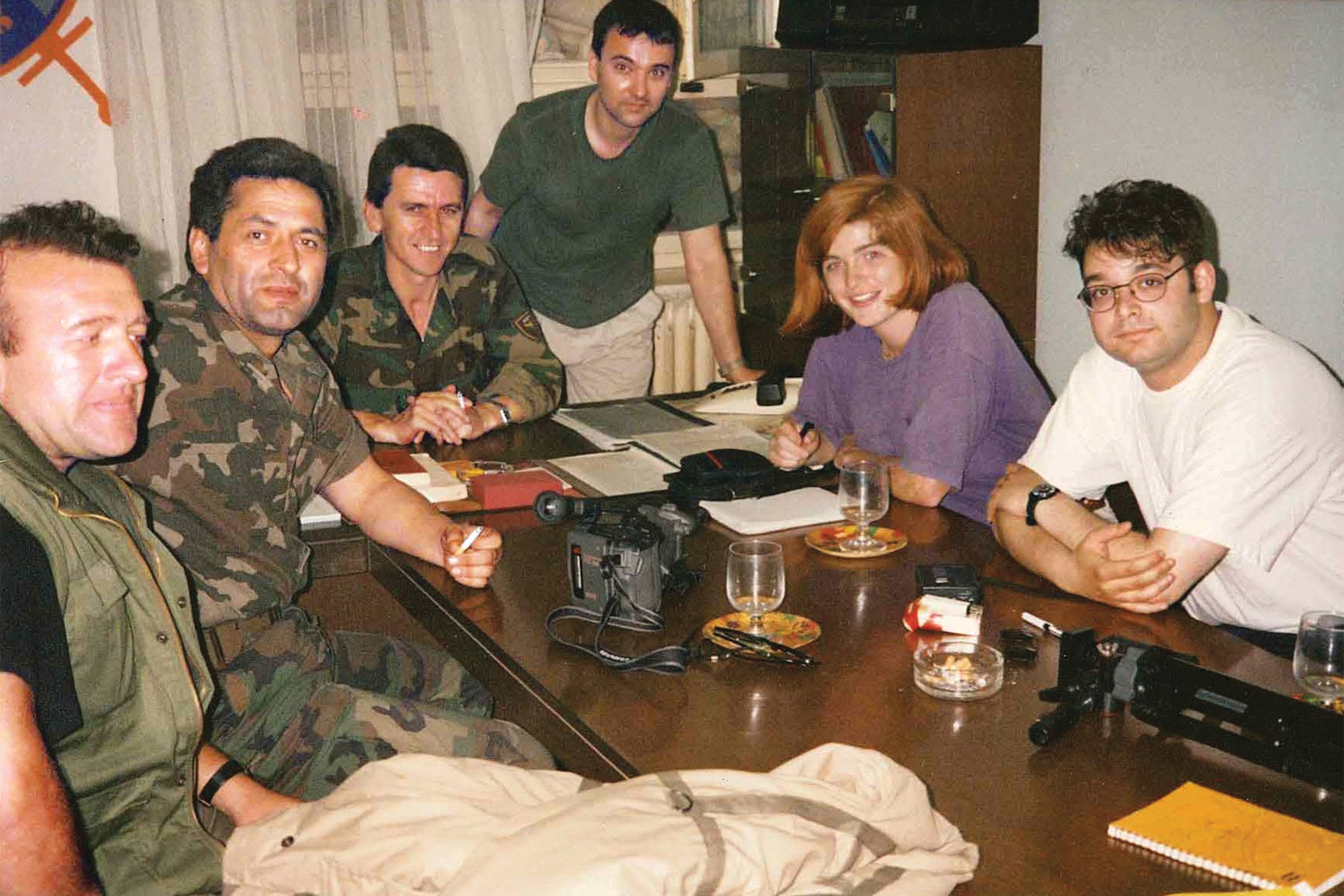

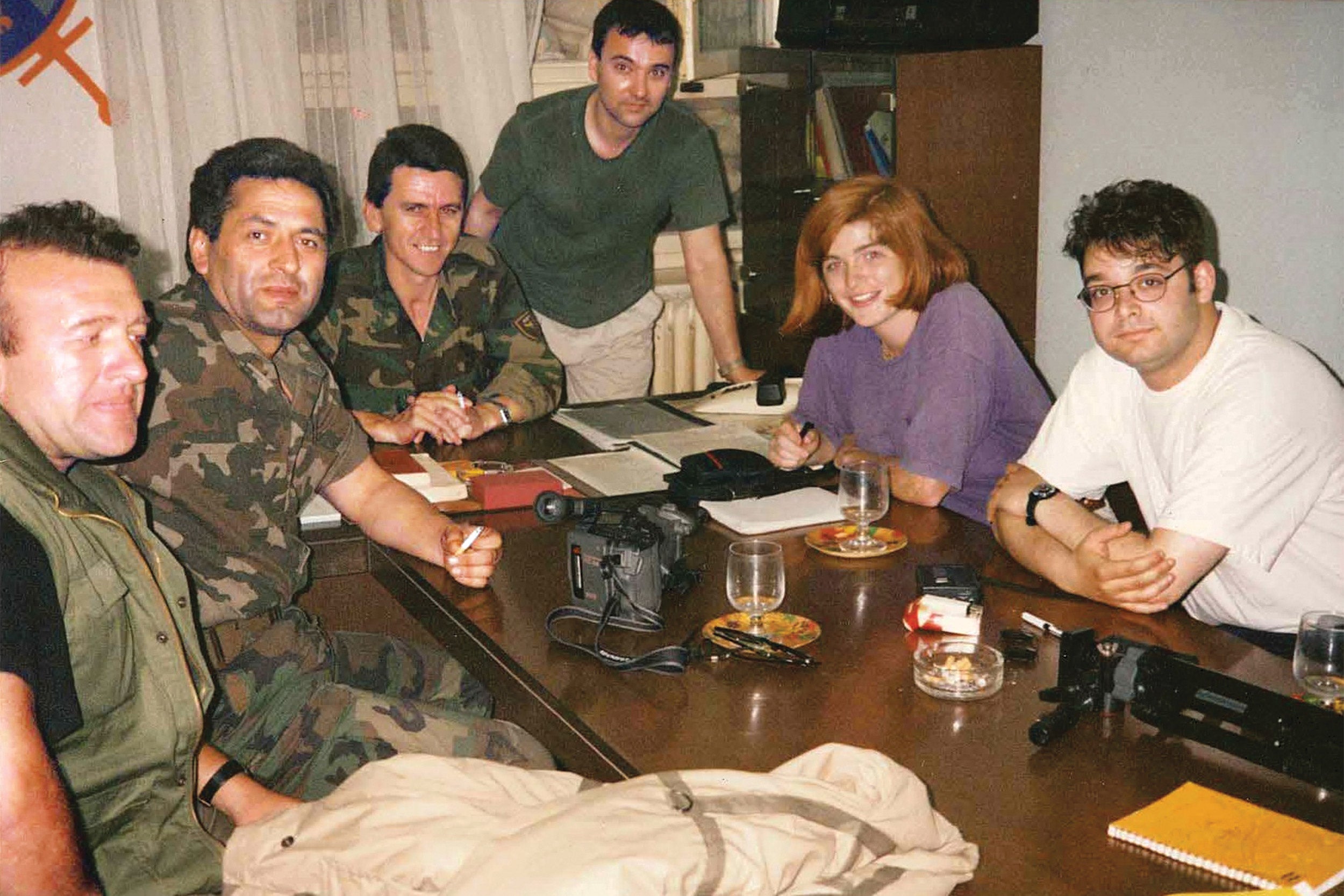

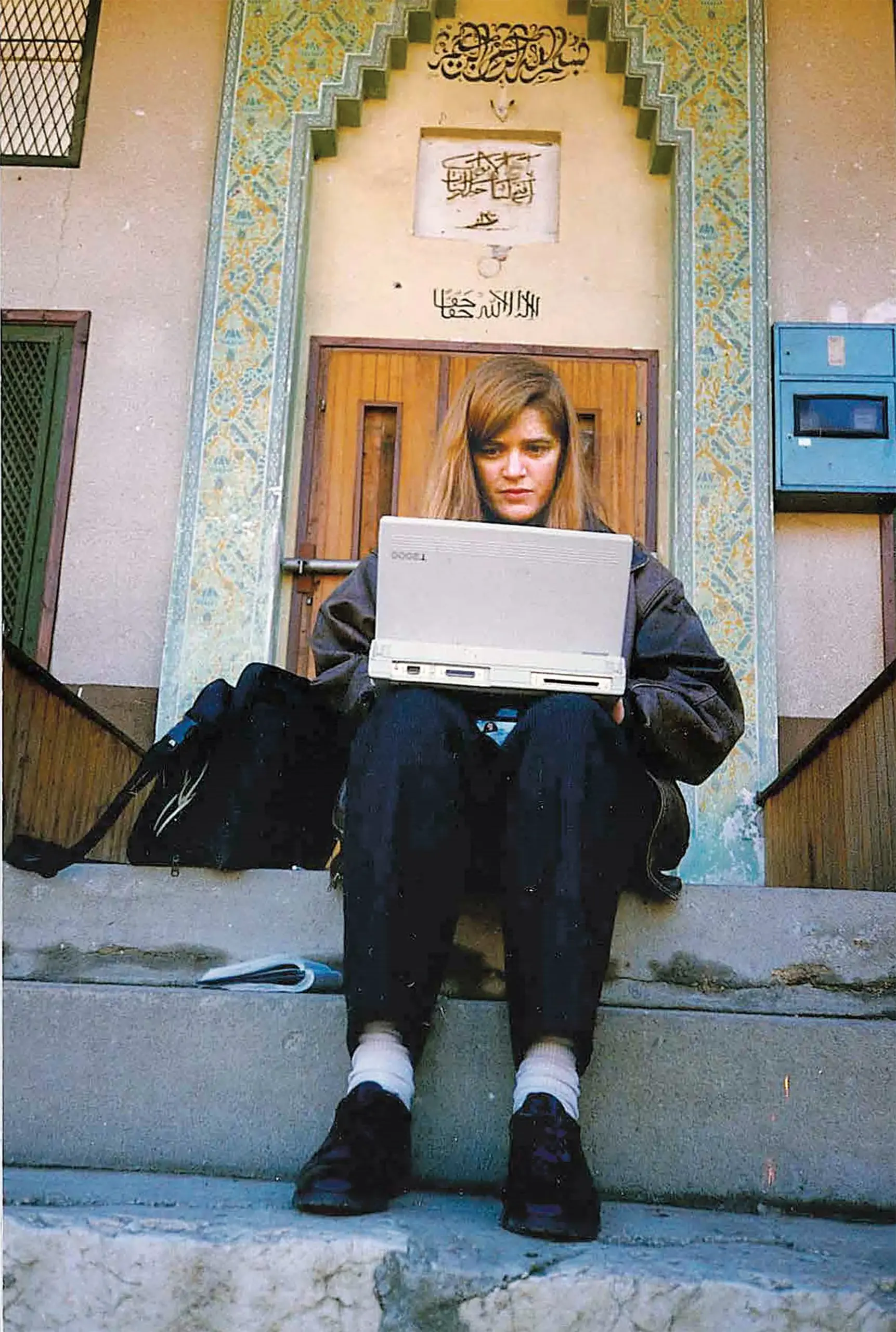

Photos courtesy of Samantha Power Credit: Courtesy of Samantha Power

In an excerpt from her just-released memoir, Samantha Power recalls her experience going from Balkans war correspondent to Law School student — and her stumbles along the way.

From the moment I arrived at Harvard Law School in late August of 1995, I feared I wouldn’t last. During the nearly two years I had just spent as a war correspondent in the Balkans, I found myself imagining how gratifying it would be to learn the law and pursue the arrest of Balkan war criminals as a prosecutor at The Hague. But as I struggled to adjust to my new life back in the United States, all I could think about was the place I had left behind.

The day before law school began, I had loaded up a Ryder truck in Brooklyn with two suitcases, a bicycle, and my laptop, and driven toward Boston. Just as I reached the city, NPR cut into its radio program with a breaking news bulletin: “NATO air action around Sarajevo is under way.” By my second week at HLS, U.S. air strikes had broken the siege of Sarajevo and brought the Bosnian war to an end.

From my new, shared apartment in Somerville, I amassed a steep phone bill, frantically calling my reporter friends in Bosnia and making them hold their phones in the air so I could hear the background sounds of honking horns and celebratory music being played by people finally freed from more than three years of horrific violence. I surrounded myself with reminders of what I had left behind, placing on the living room mantel a 40-millimeter shell that had been engraved and turned into a decorative sculpture.

My instincts continued to reflect the fact that I had spent the better part of the summer living in a city under fire: the loud scrape of a desk being moved or a library cart being pushed sent me ducking for cover. Meanwhile, simple conveniences — like a light switch — suddenly delighted me. When I visited the local supermarket, I was now paralyzed by all the options. In Sarajevo, I had counted myself fortunate to find a carton of juice priced like a bottle of Bordeaux, but in Cambridge, I was confronted by more than a dozen flavors of Snapple alone. For two years, my journal reflections had been decidedly grim, but trivial discoveries now passed for big news: “We have cantaloupe Snapple!” I marveled in one entry soon after school started.

My reacclimation to America happened slowly, and when Mort Abramowitz, my mentor from my first post-college job, questioned “why the hell you’re in law school,” I admitted I was wondering the same thing.

I didn’t lack the ability to focus — I could bury myself in the library for hours without noticing the setting sun. But I just couldn’t make myself care about the topics we were studying. In “One L,” Scott Turow’s memoir of his first year at Harvard Law School, he compares studying case law to “stirring concrete” with his eyelashes; this description seemed a perfect encapsulation of how I felt reading Civil Procedure cases late into the night.

I was also not that quick a study. I became flustered when called upon in class, stammering answers that other students quickly tore apart while a hundred pairs of eyes drilled into my back. When my professors interrogated me, I tried to keep my composure by making an insistent mental note that featured one of the Bosnian Serb war criminals I had hoped to eventually help bring to justice: “This professor is not Ratko Mladić, he’s not Ratko Mladić, he’s not …” But hours after class ended, my cheeks often still felt flushed with embarrassment.

On Oct. 29, nearly two months into law school, I picked up The Sunday New York Times at the bottom of my Somerville stoop. There, in the upper left-hand corner, was a huge headline: SREBRENICA: THE DAYS OF SLAUGHTER. A reporting team had spent weeks preparing a special investigation that contained previously unpublished details of the systematic murder of Srebrenica’s men and boys.

As I sat reading, I understood what writers reflecting on the Holocaust meant when they described the human capacity to “know without knowing.” I had covered the fall of Srebrenica and had read all of my friend David Rohde’s articles in The Christian Science Monitor about it. Yet my reaction to the Times exposé confirmed how wide the chasm can be between holding out hope that something is not true and actually absorbing devastating facts in all of their finality.

I looked back at my own actions and wondered why I hadn’t done more. “I don’t know how that could have been me there,” I wrote in my journal. “I was the correspondent in Munich while the bodies burned in Dachau … I had power and I failed to use it.” In beating myself up, I was clearly exaggerating my actual power back in Sarajevo. I had been a freelance journalist, running my laptop off of a jury-rigged car battery. President Bill Clinton led the most formidable superpower in the history of the world. The president of the United States had not needed my help if he was to be spurred to action.

Nonetheless, I felt at sea. I was sure very few of my Law School classmates were actually aware of The Times investigation that had sent me spiraling, and even those who had seen it would probably have considered it “too depressing” to read. Powerless to affect the fate of men already killed, I decided that I could at least raise awareness on campus.

In a move that at the time felt as bold as choosing to live under siege in Sarajevo, I asked my Contracts professor for permission to make an announcement before class. “I apologize for using this forum,” I said nervously after taking the floor. “But I just wanted to draw your attention to something that will be in your mailbox later.” I previewed the article, which documented “the largest single massacre in Europe in fifty years.” My lips quivered as I rushed to try to finish. “So please read it. Thanks.”

After class I met up with a new friend, Sharon Dolovich, who had done her Ph.D. in political theory at Cambridge University and seemed genuinely moved by the revelations about Srebrenica. Sharon and I dropped by the Law School copy room to collect the 500 Xeroxes I had ordered earlier in the day. Together, we solemnly stuffed a stapled copy of the article into the mailbox of each first-year law student. A few of my classmates approached me later to thank me for alerting them to what had happened. But I got the feeling that most found me off-puttingly intense.

After saying goodbye to Sharon, I made my way to the law library. After a restless hour in a carrel, I wandered to the nearest phone to collect my answering machine messages. I heard the voice of my friend, the journalist Elizabeth Rubin, who had just returned to New York from Sarajevo.

“Power, I don’t know if you’ve heard,” she said. There was a pause, and then what sounded like muffled crying. “It’s David.”

Another pause. “Um … he’s been abducted.”

I flashed back to all that my friend David Rohde had written, doing more than any reporter to uncover Ratko Mladić’s summary executions. “No! No! No!” I said, holding back tears as I raced to the bike rack and began fumbling with my lock so I could get home.

When I reached my apartment, I stood in the kitchen with no idea what to do. What more could I contribute to finding David that the U.S. government, the U.N., and the press corps weren’t already doing? I defaulted to what I usually did when I was in a bind, calling Mort.

He was constructive and typically specific. He told me to call President Clinton’s Bosnia envoy Richard Holbrooke — who, in a fortunate coincidence of timing, had just arrived in Dayton, Ohio, for peace talks with the warring factions. He also told me to call Steve Rosenfeld, who edited The Washington Post’s editorial page.

Unable to get through to Holbrooke, I (somewhat absurdly) asked the hotel receptionist in Dayton to pass on a message — verbatim:

“David Rohde has been abducted in Serb territory.

Please make him the lead item in the peace talks.”

When I connected with Rosenfeld, I begged him to write an editorial demanding that the U.S. government secure David’s release before proceeding with the Dayton talks. “He’s the only Western eyewitness to the mass graves,” I implored. “He’s in profound danger.”

Rosenfeld explained that the next day’s paper had already gone to press. “Well, if we don’t do something quickly, it will be too late,” I warned. “You have to understand: people don’t just disappear in Bosnia. We have a short window to shame David’s captors into not harming him, but it is closing.”

Rosenfeld gave me an opening. “If you want to write something,” he offered, “we will run it.”

Less than 36 hours after I heard Elizabeth’s message, The Washington Post ran my op-ed. The essay, printed Nov. 3, 1995, concluded: “I relay David’s odyssey because he is my colleague and my dear friend. American officials claim they can do no more than ‘raise the issue at the highest levels.’ David did more. Why can’t they?”

By nightfall, the Serb authorities acknowledged that David was in their custody. Had they planned to kill him, they would never have admitted to detaining him. I now believed that his family, who had staged a protest outside of the Dayton airbase where the Bosnia peace talks were taking place, would get him back.

David was released 10 days after he was seized. Once free, he revealed that he had doctored the date on his expired press pass and driven into Serb territory, where he found the first of the gravesites and evidence of murder: piles of coats, abandoned shoes, Muslim identity documents, even canes and shattered eyeglasses.

But as was David’s wont, he had pushed his luck, trying to find even more. He had been arrested at rifle-point at the second grave, just as he was preparing to photograph two human femurs he had discovered. Because he was carrying a camera, a map with suspected gravesites circled, and film stuffed into his socks, the Bosnian Serbs labeled him a spy.

His captors forced him to stand through the night, denying him sleep. They threatened him with a lengthy stay in a Bosnian Serb prison camp, and even with execution. After three days of threats, fearful that he would be shot if he continued to hold out, David considered telling the interrogators whatever they wanted. But a friendly guard whispered in his ear that he knew David was a journalist. He urged him to stand firm. This gave U.S. diplomacy and public advocacy time to succeed.

I was thrilled by David’s release and rushed to Logan Airport to be part of the crowd that welcomed him. After the dark discoveries of the previous months, the sight of David being reunited with his family felt like a sudden burst of light.

Close to midnight on the day of his return, I heard a knock on the front door of my Somerville apartment and saw David outside. We stayed up until daybreak, talking about what he had seen and gone through. We also began a debate, which we continue to this day, about when journalism is most effective in prodding change.

Credit: Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The evidence David gathered was a factor in helping convince the Clinton administration to launch the U.N.-authorized bombing raids that so quickly ended the war. Even though I was now stuck in law school, I told him that he had single-handedly given me a new appreciation for the power of the pen.

I returned to Sarajevo twice during my first year in law school, once over Christmas and then again for summer break. I loved being back among my friends, seeing the universities reopened, and watching the markets and cafes bustling with life. Witnessing even a flawed peace gave me a sense of closure, which I had craved.

Unfortunately, almost as soon as I arrived back in Cambridge for my second year of law school, I found myself struggling to breathe properly. The ailment that my college boyfriend had called “lungers” was back with a vengeance. In college, these bouts of constricted breathing were a nuisance, an inconvenient background occurrence that never interfered with my life. But now I was unable to concentrate on anything other than whether I would be able to take a proper breath.

For the first time, I grew so rattled by this mystery ailment that I could not sleep. Even when I managed to doze off for a few hours, when I awoke, I would experience a split second of deep, regular breathing before recalling the debilitating constriction of my lungs, which would promptly return.

After several weeks of mounting torment, I took a long run along the Charles River in the hopes that it would necessitate inhaling large amounts of air. Still running after an hour, I maneuvered along the paved roads near MIT to head back to my apartment. I was so focused on my breathing that I didn’t look where I was running and tripped on an uneven sidewalk slab and landed in a pile of shattered glass. Both of my knees were lacerated and began bleeding profusely.

I hobbled as quickly as I could to the University Health Services. When the doctor asked what had happened, I told him I had been struggling to breathe and had not paid proper attention to where I was stepping. He asked if I was experiencing anxiety.

“No,” I said, “the complete opposite. I was a journalist in Bosnia, and I think I find the lack of stress here on campus very hard to get used to.”

He asked if I would like to be prescribed something to settle my nerves. I told him I was completely fine and needed nothing other than a good knee cleaning so as to avoid an infection. As I was speaking, I glanced down and saw that my knees bore shards of gravel and glass and my white running socks had turned crimson with blood.

“On second thought,” I said sheepishly, “I’ll take whatever you recommend.”

Within 48 hours, the antianxiety medicine worked wonders; once I started breathing normally and focusing on my classwork, I pushed the incident — and my lungers — to the back of my mind. It would be years before I would begin to explore their source.

Ambassador Samantha Power is the Anna Lindh Professor of the Practice of Global Leadership and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and William D. Zabel ’61 Professor of Practice in Human Rights at Harvard Law School. This piece is excerpted from her new book, “The Education of an Idealist,” published by Dey Street Books. Copyright © 2019 Samantha Power. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.