In 1321, when Isabel of Bury stabbed a cleric to death in the London church All Hallows-on-the-Wall, she had a simple choice: flee the city, face justice, or attempt to claim sanctuary in the holy place where she’d committed her crime. She chose the latter.

In “Felony and the Guilty Mind in Medieval England,” Harvard Law School Assistant Professor Elizabeth Papp Kamali ’07 situates Isabel’s predicament in the context of 13th and 14th century notions of crime and punishment. Her recently published book explores how English courts considered a defendant’s state of mind in judging guilt or innocence, outlines the many factors that led to the relatively low conviction rates of the time, and explains the three essential elements of a felony crime: that it was reasoned; not committed by necessity; and wickedly intended.

Harvard Law Today recently sat down with Professor Kamali to discuss her research; trial by ordeal in medieval England; the genesis of its replacement, trial by jury; the use of torture in the criminal justice process; and what became of Isabel’s audacious attempt to avoid the gallows.

Harvard Law Today: Can you help set the stage by telling us a little bit about the criminal justice system in 12th and 13th century England?

Elizabeth Papp Kamali: One of the things that I find fascinating about medieval English law is the transition from a criminal justice system in the 12th century that relied on trial by ordeal, to a system dependent upon juries to issue final felony verdicts by the early 13th century. That’s a world that came into being after the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, when the Catholic Church withdrew priests from administering trial by ordeal. England was then forced to choose another method of proof.

HLT: Can you explain trial by ordeal?

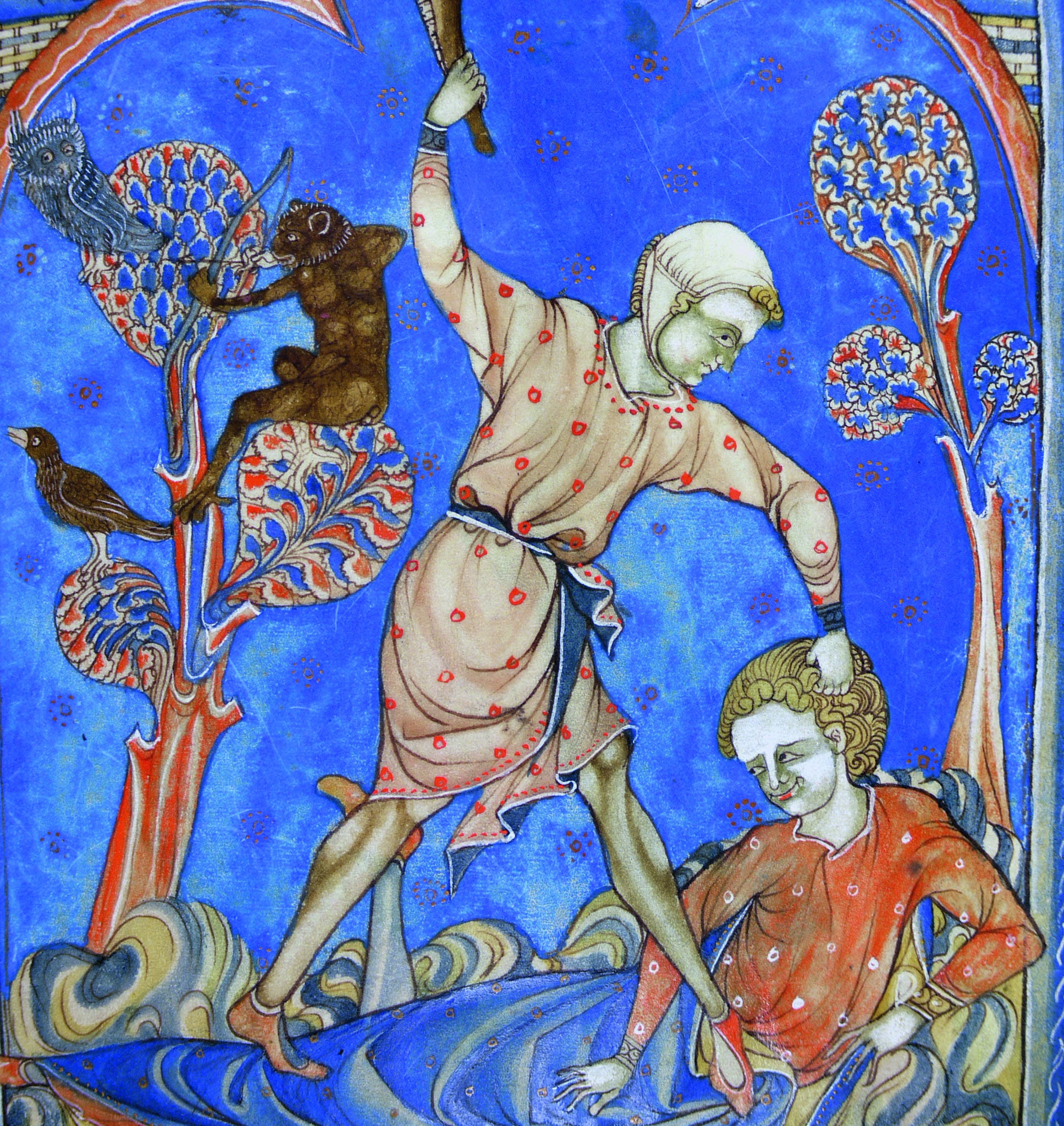

Kamali: In Latin, it’s referred to as the judicium Dei, the judgment of God. The two methods used most typically in England were trial by cold water and trial by hot iron. In trial by cold water, a person would be dunked into a cistern. If they sank, they would be declared innocent, because the water had accepted them. If they floated, they would be declared guilty.

In trial by hot iron, the priest would heat an iron, and at the appropriate point in the service, the accused would grasp the hot iron, walk a certain number of paces, and put it back down. The hand would be bandaged, and then three days later, the hand would be examined to see, not if the person had been burned or not burned, but whether the hand was healing or festering. If the hand appeared to be festering, they would be pronounced guilty. And if the hand seemed to be healing, they would be pronounced innocent.

Both of these ordeals were preceded by a solemn liturgy administered by priests.

HLT: Why did the Fourth Lateran Council end trial by ordeal?

Kamali: There was more than one impetus for change. The abolition of priestly involvement in the ordeal was one of several reforms made by the Fourth Lateran Council, which also banned priests from being barbers or surgeons. This reflected the idea that priests, who are entrusted with sacred functions, shouldn’t be involved in matters that could result in blood pollution. It was part of a broader desire for reform of the clergy, and for a clearer separation of the clerical orders from the non-clerical.

That said, the impetus for getting rid of the ordeal also came from influential theologians writing in the 12th century, Peter the Chanter being one that I deal with in my book. He expressed concern about the accuracy of trial by ordeal. For example, he shared a story about an English pilgrim who traveled abroad with a companion, returned alone, and fell under suspicion of having killed his companion. Because the pilgrim knew he was innocent, he agreed to undergo trial by ordeal. The pilgrim failed the ordeal and was executed. A short while later, his traveling companion returned home safe and sound.

Peter the Chanter used stories like this to argue that the ordeal didn’t work. He felt that, in judging serious matters, one should have proof as clear as the light of day. The ordeal, in his estimation, did not offer proof as clear as the light of day.

Other theologians expressed concerns that the ordeal was a tempting of God, that it was wrong to basically say, “God, come down and adjudicate this case.”

HLT: How did England adjust to the elimination of trial by ordeal?

Kamali: The interesting thing is that England already used a jury of presentment—the ancestor of a modern grand jury—to determine whether someone suspected of a crime ought to be tried by ordeal. This helps explain why England, not long after the Fourth Lateran Council, could make a swift transition to jury trial. With juries of presentment already involved in felony cases, it was a relatively small step to have juries issue final verdicts as well.

HLT: How did the new trial by jury system that emerged in the 13th century work?

Kamali: The records of felony cases tend to be very brief, giving a sense of a quick trial. The defendant had no counsel, and a jury of 12 men—in some instances 12 men who might have known the defendant, or the victim, or both—was given the task of deciding whether the man or woman before them was guilty or innocent.

If found guilty, a defendant typically faced capital punishment, a walk to the gallows. In actuality, most defendants who made it to trial were acquitted. And many who weren’t acquitted received pardons. Although a significant number of people were convicted and subject to the capital penalty, looking at the relatively low conviction rate puts things in a different light.

The other thing to know about the criminal justice system in the 13th century is that, while capital punishment was the penalty for most felonies, there were significant escape valves. In the case of an altercation where someone was wounded, very often the people involved might flee town and wait to hear more before returning. They might flee to a church and take sanctuary, at which point they had the option of confessing and then leaving England permanently.

In other instances, a man who was literate, or at least could feign literacy well, might claim benefit of clergy, which would take the case out of the royal courts and into the church courts, where the death penalty was off the table. These mechanisms winnowed down the number of potential defendants who actually ended up facing trial.

HLT: What did the king think of the idea of someone who might have taken, perhaps, minor holy orders—often referred to as a clerk—escaping the state’s criminal justice system by having their case tried by Church Court instead? Wasn’t that a big loophole?

Kamali: In the reign of Henry II, there was the famous controversy with Thomas Becket over who gets to punish ‘criminous clerks’, as the history books tend to refer to clergy accused of committing serious crimes. The compromise that was eventually worked out involved an initial appearance before royal justices by a person accused of felony who wished to claim benefit of clergy. A jury would decide whether they believed he was guilty or innocent before handing him over to the church authorities.

Typically, a church official or representative of the local bishop would be called into the courtroom and be asked, “Is this one of your men? Do you claim him as a cleric?” Most often, the answer was yes. And the defendant was then handed over as either guilty or innocent to the church authorities, who might prescribe some kind of punishment or purgation, but not the death penalty.

HLT: In your book, you write of crimes as “felonies committed feloniously.” What did medieval English people think about what that meant?

Kamali: The word “felony” itself in this period sometimes indicated a category of crimes, such as homicide, theft, or arson. But the fact that we could also then tack on the adverb “feloniously” to this phrase suggests that there was some further meaning.

Felony was a word in widespread usage, in a way that is not true today. When you watch “Law and Order,” you might hear about a felony. But when we talk about people who have treated us wrongly, or wicked characters in a movie, we don’t say, “Oh, they’re so felonious”. We have dropped that usage.

But in the 13th and 14th century, words of felony were more widely used. An adaptation of a biblical tale, for instance, might refer to Herod as a felon or describe Judas as having acted feloniously. Words of felony were a mark of opprobrium, signaling that a person had acted in a truly evil or wicked or unforgivable manner.

HLT: What would be an example of a felony committed feloniously, as opposed to just a felony?

Kamali: In my book, I primarily illustrate alleged crimes that were not considered felonious. When people were convicted in medieval courts, very often the trial record doesn’t give historians a lot to work with in terms of explanation. More typically, a trial record provides a bit more insight into what jurors were thinking when they decided that a defendant had not acted feloniously.

Examples of cases that weren’t considered felonious include alleged crimes committed by youth or by persons afflicted with a mental illness, sometimes described in Latin as a “lunatic” (lunaticus), “frenzied” (phreneticus), or “out of [their] mind” (extra mentem).

An alleged crime was also not felonious when a person had acted under severe duress. For instance, a woman who committed a crime with her husband might be granted a reprieve, while her husband faced the gallows, if she could persuasively argue that she could do no otherwise than obey her husband’s command and therefore hadn’t exercised her own free will.

It’s through these cases that are explicitly described as not felonious that one can piece together a paradigm of felony. I argue in the book that the paradigm of felony was an act involving rational thought or deliberation, the exercise of a person’s will in the absence of necessity, and sometimes the additional factor of evil or wickedness, which gets at the heart of the understanding of felony found in imaginative literature.

That aspect appears most clearly in self-defense narratives, where the legal record often describes the person who ended up dead as having attacked the self-defender in a vicious, relentless manner, sometimes driven by anger. The self-defender, by contrast, has his back up against a wall, or against a dike, in these trial narratives crafted with the goal of securing a pardon. He has no alternative to save his own life but to strike out with deadly force against the person attacking him.

HLT: Professor Martha Minow’s new book, “When Should Law Forgive?” explores how forgiveness can be an integral aspect of achieving justice. Hearing about how thoughtfully medieval English juries approached the work of judging felony crimes, I wonder what role forgiveness played in their deliberations. Can we draw any parallels?

Kamali: I’m often asked whether there are lessons for today that can be drawn from my book. One of those lessons is not that we should adopt the medieval system of felony adjudication with the gallows for all who are convicted!

But perhaps we can learn something from our common-law ancestors. Medieval English texts emphasize the redemptive potential of humanity and the idea that it’s very hard to judge another person’s mind. In fact, we can really get that wrong. Only God, they believed, could fully judge a person’s mind and heart. Moreover, a person who is truly wicked today could become a saint tomorrow, and the converse of that.

Saint Augustine would be an incredible example. He had his mother Monica pestering him relentlessly to get him on the path towards sanctity, a path he describes in his famous “Confessions.” Another example would be Saint Paul, who started off as a persecutor of Christians, and then became one of the pillars of the church. On the flipside, you have someone like Judas, who began as an apostle of Jesus, and then took a path that carried him away from redemption.

In addition, the Catholic sacrament of confession is based on the idea that a person might commit sins that could send them to hell. However, if the person were truly contrite and made a clean breast of it, confessed fully, vowed to make penance, and received absolution, they walked out of that church a new person, and with a clean slate to start again.

That way of thinking is something we could use a little more of today in our secular society—the idea of second chances, and of not writing people off when we perceive that they have done something very harmful. There is redemptive potential in everyone.

HLT: What was the role of torture in medieval England? Were accused felons being thrown in the dungeon and interrogated by brutal means?

Kamali: The standard story about what happened when the church withdrew the ordeal is that England took a path toward jury trials, while continental Europe took a path toward inquisition and a heavy reliance on defendants’ confessions. And sometimes in order to get that confession, they used torture. What I demonstrate in my book, first of all, is that confession was widely used in English procedure as well. I also suggest that England was no stranger to torture, arguing that this is an apt word to describe the mechanism by which consent to jury trial was sometimes secured.

After trial by ordeal was withdrawn by the Fourth Lateran Council, the defendant had to consent to its replacement, the jury trial. In the earliest days of jury trial for felony, the 1220s, when someone refused to agree to a jury trial, the trial might proceed regardless. The jury would issue a verdict. Then a second jury, a super jury of knights, would issue a verdict, confirming the initial one. The idea was that extra process would rectify the lack of consent.

Within decades, the royal courts developed the procedure of peine forte et dure. If a defendant refused to consent to jury trial, they would be placed in prison on a severe bread and water diet. Weights would be placed on the defendant’s body until they either agreed to jury trial or died.

For a person who feared they would be convicted at trial, the path of peine forte et dure offered a potential benefit. If they died without having been convicted at trial, their property was not forfeited. Some defendants might choose this route to save their families’ livelihood.

HLT: Can you give us an example of a case that you found particularly interesting or illustrative?

Kamali: In an early fourteenth-century case, a woman named Isabel of Bury was in the London church of All Hallows on the Wall chatting loudly with another woman. A clerk scolded them and ordered them to leave. Angered by this, Isabel responded by stabbing the clerk in the chest, killing him. That alone is interesting. But, what’s most interesting is what comes next.

Isabel appears to have known something about sanctuary procedure. Rather than leaving church to face trial, Isabel tried to claim sanctuary. The king’s authorities were initially at a loss about what to do. They had never had a case in which somebody committed their felony in a sanctuary space, and then said, “I’m not leaving.” They sought an opinion from the church authorities. A representative of the bishop of London produced a decretal, an official letter, saying that a person who committed a crime within a church could not then avail themselves of sanctuary. Slippery-slope concerns likely inspired the church’s response, the fear being that otherwise felons would routinely try to commit their felonies within a sanctuary space in order to take advantage of that protection.

As for Isabel, after a time in Newgate prison, she was hauled before the royal justices. Again demonstrating some familiarity with felony procedure, Isabel at first stood mute rather than stating her plea and consenting to jury trial. The justices then warned her that if she was found to be standing mute deliberately (which was likely given the fact that she had no difficulty speaking earlier in church), she would face severe consequences. She then claimed self-defense, arguing that the deceased clerk had struck her first. Finally, Isabel chose to plead not guilty and consented to jury trial. She was convicted.

HLT: What got you interested in the field of Medieval English Law?

Kamali: During my freshman year at Harvard College, I took a class with Charlie Donahue, who is on the law faculty here. I knew nothing about law, so I remember confronting words like “torts” with some confusion. Is that a cake? I came in with zero knowledge of the law.

But I found that trying to parse medieval legal texts—we started with early English texts, Ǣthelred’s Code from approximately 603—was tremendously fun and challenging and wonderful. I took a second class with Charlie my sophomore year on continental European legal history. By junior year, with the encouragement of Charlie and then-graduate students Carol Symes and Claire Valente, I began working with manuscript material. The Law School Library had a collection of 14th-century manor court rolls, which are records of local, manorial courts handling land transactions, disputes between peasants, and other matters. I spent the summer between junior and senior year learning how to read the heavily abbreviated Latin script.

I ended up writing a senior thesis on the effects of the mid-14th-century Black Death on the operation of a manor court in Norfolk County, England. By the time I graduated college, I wanted to pursue medieval English legal history. I ultimately returned to Harvard to get my J.D. By the end of my J.D. studies, I still had the history bug. So I applied to do a Ph.D., which took me to the University of Michigan to work with Tom Green, an expert on the history of the English criminal trial jury. And the rest, we might say, is legal history.