In a season full of newsworthy Supreme Court decisions, the McGirt v. Oklahoma ruling was a landmark for Native American rights, reshaping the legal relation between the federal government and the tribes. In a 5-4 decision on July 9, the Court ruled that much of eastern Oklahoma remains a reservation, where Indian citizens are not subject to state jurisdiction.

Robert Anderson, the Oneida Indian Nation Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, says that this decision resolves decades’ worth of legal argument.

“It’s a huge victory for the tribes, and Justice [Neil] Gorsuch (who authored the decision) has emerged as a real champion of tribal rights. He is from the West and familiar with Indian reservations; he’s a conservative but he’s faithful to the law and longstanding precedent. So I think this bodes well for tribal interests going forward,” he said.

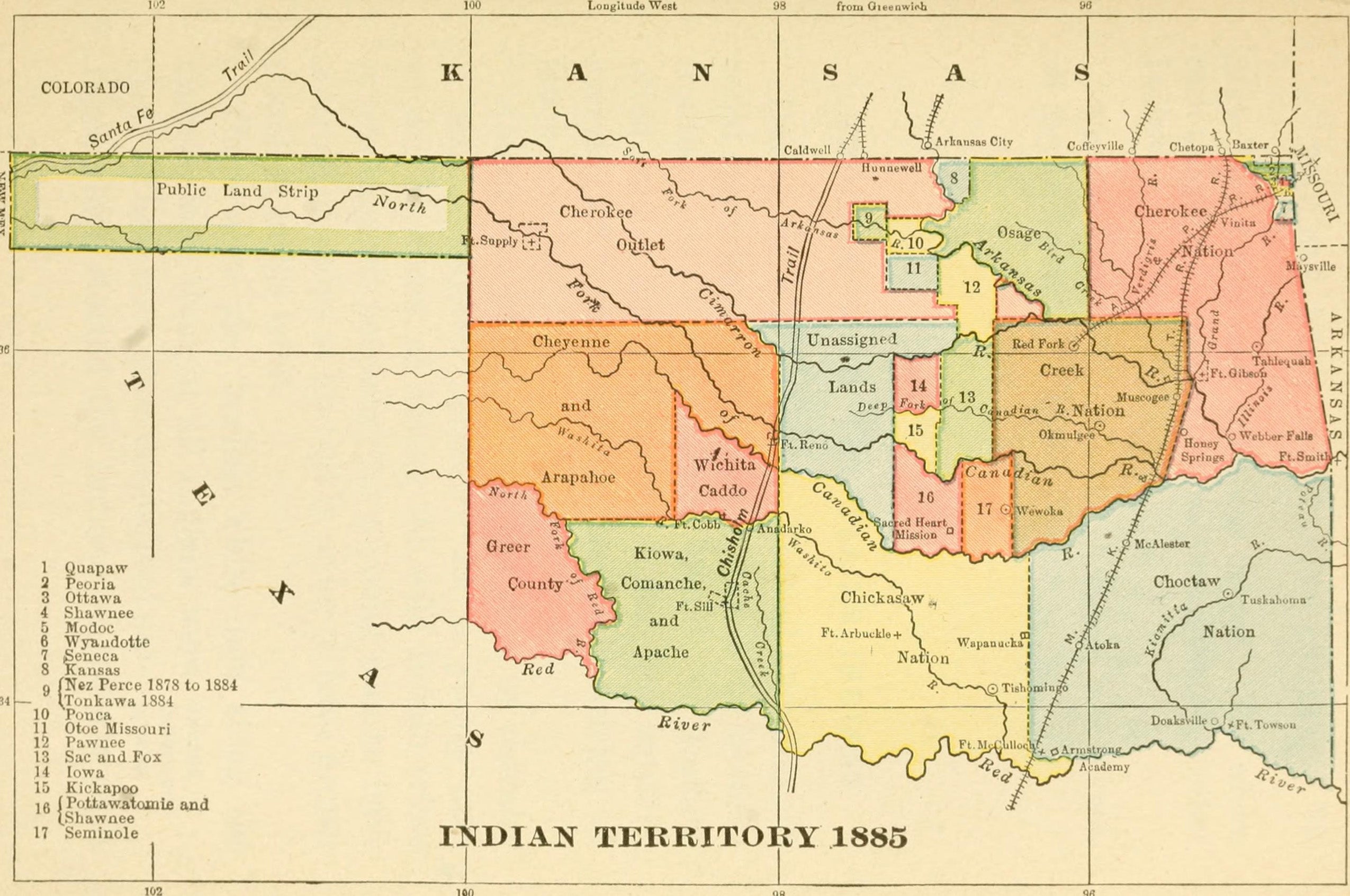

At issue was whether the Eastern half of Oklahoma, once designated as an Indian reservation, would remain such despite now having a largely non-native population. Two previous cases, Solem v. Bartlett (1984) and Nebraska v. Parker (2016) both established that Congress has the right to abolish (or in legal terms, to disestablish) a reservation if it chooses to do so. This however was never done in Oklahoma, instead the state began asserting criminal jurisdiction over the Eastern area more than a century ago, simply proceeding as if the reservation had been disestablished.

The current case was brought by Jimcy McGirt, a Creek Indian who was convicted by Oklahoma of a sex crime against a child. But it was a question of the state’s authority, not of McGirt’s guilt. The state argued that its longstanding authority would be hobbled by a decision against it; a view echoed by Justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. ’79.

But Gorsuch made the textualist argument that Oklahoma’s authority didn’t exist because Congress had never granted it. “Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law,” Gorsuch wrote.

“As Justice Gorsuch wrote, the reservation was established back in the 1850s, after the Creeks were removed from Alabama and the Southeast to what is now the state of Oklahoma, but it was promised as Indian territory,” Anderson said. “And that land was promised to them forever without having a state ever created to surround them. Then of course Oklahoma was occupied by non-Indians during the late 19th century and early 20th century, a huge influx of people onto the Creek reservation. And the question became what would happen to the Creek reservation where federal and tribal [but not state] law applied.

“The assumptions were at the time the reservation would be abolished. But Congress never said that. They may have intended that in 1901 or 1906, but they never actually took that step. And that’s basically what the Court said today, that once a reservation is established by treaty or act of Congress, only Congress can revoke it. And Congress never did that, clearly and expressly. It took Justice Gorsuch 25 pages to say that, but that’s the gist of his opinion. And so that means that the state has no jurisdiction over criminal actions involving people like Mr. McGirt who is an Indian tribal member who committed a crime against a non-Indian,” he said.

According to Anderson, this decision doesn’t mean that McGirt is likely to walk free, as he can be convicted by the tribe or by federal law. Nor does it portend a change for the state’s non-Indian population, who are still subject to state law.

“The federal government has jurisdiction over major crimes whenever the defendant is an Indian —murder, sexual assault, robbery and so on. The tribe has jurisdiction over crimes committed by Indians within the reservation, and the state retains jurisdiction over non-Indian v. non-Indian crimes. In cases where the perpetrator or victim is an Indian, the federal government will have jurisdiction instead of the state. What this decision changes is the assumption that people in Oklahoma had for many years, which is that the state has full jurisdiction over that territory, to the exclusion of the federal government on criminal matters.”

This also doesn’t mean that most Oklahoma citizens will find themselves living under different laws, said Anderson.

“It’s going to mean a change in the practical enforcement of criminal laws,” he said. “The federal government will now have to assume more jurisdiction over cases involving Indians as the victims of a crime, or as defendants in a crime. But beyond that I don’t see a lot of [practical] difference, because the Creeks and other tribes have made a lot of jurisdictional agreements with the state in terms of how they’re going to help each other out with emergency services, police protection and the like. So I don’t think there’ll be that big a change [in everyday Oklahoma life], beyond the matters of criminal law enforcement.”

Anderson says he wasn’t surprised to see Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, siding with the Court’s more liberal wing. “Frankly I was more surprised that Justice Thomas abandoned his opinion in Nebraska v. Parker [where he came down on the side of tribal rights]. Meanwhile Gorsuch kept asking ‘Where’s the text, where’s the text?’,” he said. “It’s very much like his decision on gay and lesbian rights where he said, ‘Hey, this statute says that you can’t discriminate based on sex, and that’s what it means.’”