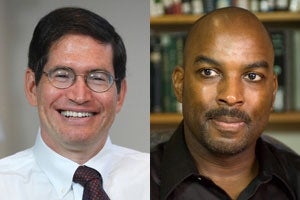

Harvard Law School Professors Michael Klarman and Kenneth Mack ’91 have both participated in the SCOTUS Blog’s commentary on Race and the Supreme Court. The Blog’s program is in celebration of Black History Month.

Klarman: Has the Supreme Court been mainly a friend or foe to African Americans?

Klarman is the Kirkland & Ellis Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. He has written extensively about the Court and racial equality, including three books: “Brown v. Board and the Civil Rights Movement” (2007), “Unfinished Business: Racial Equality in American History” (2007), and “From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality” (2004).

The conventional wisdom that the U.S. Supreme Court heroically defends racial minorities from majoritarian oppression is deeply flawed: Over the course of American history, the Court, more often than not, has been a regressive force on racial issues.

Before the Civil War, the Court sustained the constitutionality of federal fugitive slave laws, invalidated the laws of northern states that were designed to protect free blacks from kidnapping by slavecatchers, voided Congress’s effort to restrict the spread of slavery into federal territories, and denied that even free blacks possessed any rights “which the white man was bound to respect.” After the Civil War, the Court freed the perpetrators of white-on-black lynchings and racial massacres, and it invalidated a federal law designed to secure blacks equal access to public accommodations. Well into the twentieth century, the Court sustained the constitutionality of state-mandated racial segregation and various southern state measures for disenfranchising African Americans.

The romantic image of the Court as savior of African Americans derives largely from Brown v. Board of Education and its immediate progeny. To be sure, the Court’s epic 1954 ruling, which invalidated state-mandated segregation in public schools, was of enormous symbolic importance to blacks, and it helped catalyze the transformative racial change accomplished by the civil rights movement of the 1960s. In the fifteen years following Brown, moreover, the Justices not only significantly expanded the scope of that decision, but they also went to great lengths to overturn the criminal convictions of sit-in demonstrators, created new constitutional law to protect the NAACP from legal harassment by southern states, expanded the range of private actors subject to the Fourteenth Amendment’s antidiscrimination command, and upheld broad exercises of congressional power on behalf of civil rights.

But the civil rights movement disintegrated in the late 1960s, and Republican candidate Richard M. Nixon won the presidency in 1968 on a platform emphasizing law and order and opposition to court-ordered busing to desegregate schools. Ninety-seven percent of blacks voted for Democrat Hubert Humphrey that year, but only 35 percent of whites did so. Nixon’s victory at the polls translated directly into changes in the Court’s racial jurisprudence: He appointed four new justices during his first term.

Almost immediately, the new Nixon appointees began to exert tremendous influence on the Court’s racial jurisprudence. In 1974 in Milliken v. Bradley, by a five-to-four vote, the Justices barred the inclusion of largely white suburbs within an urban school desegregation decree, absent proof that school district lines had been racially gerrymandered. As a result, federal courts were disabled from accomplishing meaningful school desegregation in most cities. Nixon’s appointees comprised four of the five justices in the majority.

On another racial issue of critical importance, the Burger Court ruled in Washington v. Davis (1976) that laws making no racial classification would receive heightened judicial scrutiny only if they were illicitly motivated; showing that a law simply had a disproportionately burdensome impact on racial minorities was deemed insufficient to establish a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. As a result of that decision, federal sentencing guidelines that prescribe the same punishment for possession of five grams of crack cocaine as for five hundred grams of powder cocaine have survived constitutional challenge, even though 90 percent of crack defendants are black, while three quarters of powder defendants are white.

In the 1978 Bakke decision, the Burger Court narrowly ruled that race-based affirmative action policies would be subject to the same strict judicial scrutiny as had been applied to traditional Jim Crow legislation. Conservative justices, then and since, have read the Fourteenth Amendment, which was adopted in order to protect the newly freed slaves from racial discrimination with regard to civil rights, as a mandate of government color-blindness. The Court’s overall record on race-based affirmative action has been mixed since Bakke. The conservative justices have almost invariably voted to invalidate such programs, while the liberal justices have almost always voted to uphold them. Individual case outcomes have been determined by the votes of swing justices—first, Lewis Powell, and then Sandra Day O’Connor. But the Court has invalidated more affirmative action programs than it has sustained.

Continue reading Klarman’s article.

Mack: The Supreme Court as a Racially Representative Institution

A legal historian and expert on race and the law, Mack’s book, “Representing the Race: Creating the Civil Rights Lawer, 1920-1955,” will be published by Harvard University Press this year.

Although political scientists are fond of presenting it as a novel idea, the idea that the Supreme Court is a political institution has long been fairly obvious to African Americans and their constitutional advocates. The proposition that the Court is an institution embedded in the larger politics of the world around it was self-evident to those who had noticed the curious convergence between the narrowing of their constitutional rights and the onset of the Jim Crow era. Los Angeles civil rights lawyer Loren Miller stated a strong version of the thesis when he wrote, in the mid-1930s, that “I know that behind the scenes . . . public opinion exerts the determining role in law,” but he captured the general thrust of what had become conventional wisdom. Sometimes even the Justices have to be reminded of it, as the exchange between President Obama and Justice Alito during this year’s State of the Union attests, but to those who have had perhaps the largest stakes in the question, its answer has been clear for quite some time. The first two African Americans to sit on the Court, Justices Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas, were keenly aware of this issue. Each man approached it in a different way, as will, no doubt, the newest Justice, Sonia Sotomayor.

When Marshall joined the Court in 1967, the nature of that institution’s relationship to the politics of race changed irrevocably. For all of its previous history, African Americans and their advocates had petitioned the Court, literally and figuratively, for redress of their grievances, so much so that Loren Miller gave his exhaustive history of black Americans and the Supreme Court, published one year before Marshall took his seat, a simple title: The Petitioners. Marshall’s confirmation changed the nature of the Court from an institution that black Americans petitioned to one where they had political representation. Indeed, politics of the most conventional sort lay behind that historic moment. When President Kennedy elevated Marshall to the Second Circuit in 1961 and Johnson cleared the way for him to ascend to the Court six years later, both Presidents understood that black voters remained dissatisfied with the pace of executive action on civil rights. Musing to Doris Kearns, Johnson confessed that Marshall’s nomination was one of his last chances to do something for African Americans who had made so much effort to “register and vote for the people who’d do a good job for them” but continued to be frustrated by barriers to equality. Marshall evidently had reciprocal sentiments. He called Johnson “my President,” while Nixon was “your President,” in speaking to his early clerks.

Throughout his tenure on the Court, Justice Marshall seems to have regarded himself as a political representative of those who had never participated in its deliberations. In a 1973 case involving the permissibility of a $50 fee for a bankruptcy filing, for instance, Marshall invoked his unique experience, writing that “no one who has had close contact with poor people can fail to understand how close to the margin of survival many of them are.” More significant was his draft opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, where he observed, acidly, that the Court had never had a black “Officer of the Court” and only had “three Negro law clerks.” His biographer Mark Tushnet credits the draft, after it was reshaped a bit, with convincing Blackmun to join the Justices who voted to uphold some forms of affirmative action. One of his last acts as a Justice was to ask a lawyer arguing a search and seizure case: “Was the defendant in this case by any chance a Negro?”, producing an embarrassed answer in the affirmative. Within the Court’s deliberations, Marshall’s stories of his experiences as a black man who had grown up under Jim Crow were one of the things that his colleagues remembered most about him. It was not self-evident that a black Justice should act this way. Marshall’s mentor, for instance, William Hastie, the first black federal Circuit judge, adopted a pose of studious non-racialism of word and deed after he ascended the bench in 1949. Marshall consciously chose to blaze a different path.

For Justice Clarence Thomas too, the politics of racial representation shaped both how he got to the Court and what he did once he arrived there. Indeed, the only thing that would have produced more controversy than nominating a black conservative to fill Marshall’s seat would have been to have nominated a white lawyer of any political orientation. The idea that there was now a “black seat” was now so embedded that it led President Bush and then-judge Thomas, both critics of race-conscious governmental decisionmaking, to go forward with a nomination that few could convincingly contend was anything other than that. Conventional racial politics also played a role in his confirmation. After charges surfaced that he had sexually harassed Anita Hill, a black subordinate, polling data showed that his support among black voters actually rose rather fell. That support was one of the key factors that led a Democratic-controlled Senate to confirm him.

Once ensconced on the Court, Justice Thomas sat uncomfortably in the shadow of his predecessor. “These people are mad because I’m in Thurgood Marshall’s seat,” he reportedly said of his critics. At the same time, Thomas seems to share his predecessor’s view that a significant part of his role is to speak for those whom the politics of race have marginalized within the institution. Although an ardent critic of race-based government practices, Thomas, for instance, took the time to write separately in a ruling on school desegregation early in his tenure. Lauding state-sponsored historically black colleges as representing “the highest attainments of black culture,” he made clear his caution about a ruling that would endanger them. In the context of pre-college education, too, Thomas has gone on record to distinguish himself from his conservative allies in emphasizing that black schools “can function as the symbol and center of black communities.” More than any other Justice in the Court’s history, including Marshall, Thomas makes a point to cite black writers such as Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois to ensure that their thoughts are made part of the record of the Court’s deliberations. As scholars such as Randall Kennedy and Angela Onwuachi-Willig have argued, Justice Thomas undoubtedly views himself as a “race man” on the Court, to put it in terms that Marshall himself would have understood, whether or not one agrees with the uses to which Thomas has put that racial politics.

In nominating Sonia Sotomayor as the newest member of the Court, President Obama made clear that her experiences as the daughter of Puerto Rican migrants to New York were part of the reason for her selection. In doing so, he merely followed in the tradition of the first President Bush, differing only in making explicit what everyone already knew. As a court of appeals judge, Sotomayor famously went on record on the subject of minority group status and judicial voice. Although she disavowed those specific observations, it seems clear that she will eventually find her unique role within the Court as a representative of those who had no place there before. In doing so, she will be following the path that Justices Marshall and Thomas, each in differing ways, marked out before her.