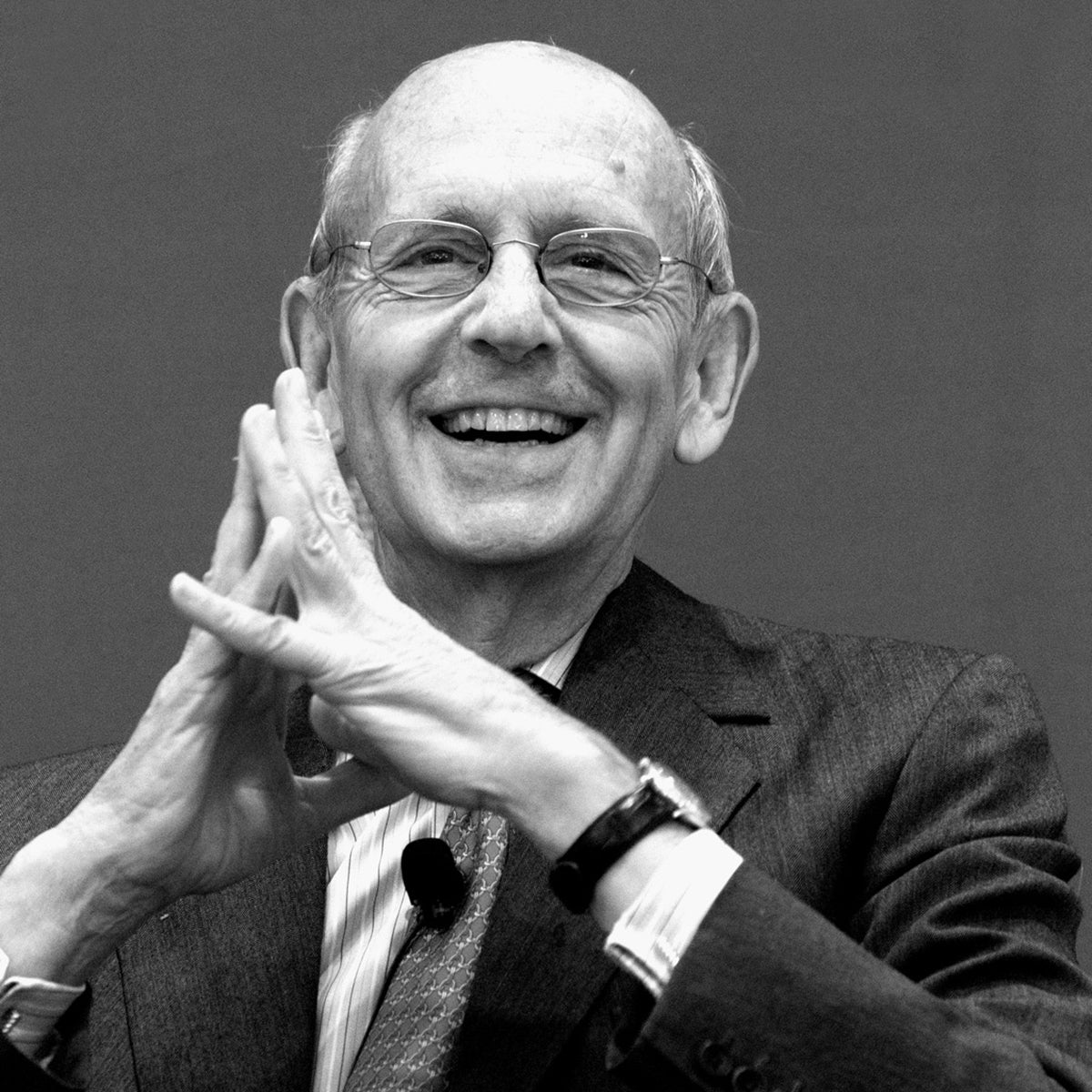

With the announcement of Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer’s retirement has come an outpouring of testaments to his transformative presence on the Court. Richard Lazarus ’79, the Howard and Katherine Aibel Professor of Law, who has represented the United States, state and local governments, and environmental groups in the United States Supreme Court in 40 cases and has presented oral argument in 14 of those cases, reflects on Justice Breyer’s “striking pragmatism” — and passion — during his judicial tenure.

Justice Stephen Breyer’s announcement earlier today that he will be departing the Court deserves far more than its principal immediate reception — an audible, collective sigh of relief from liberal activists understandably desperate to have President Biden name Breyer’s replacement while Democrats still control the Senate. Now is the time to reflect on what has made Breyer such a remarkable Justice during his twenty-eight years on the Court.

During Justice Breyer’s more than quarter century on the Court, commentators have routinely associated the Justice with the “liberal wing” of the Court. That is understandable. After all, it is easy to find major cases in which Breyer’s vote made the difference — that is what regularly happens on a Court, like the Court on which Breyer has sat since 1994, that has routinely decided most of its highest profile cases by five to four votes. In those Court rulings cheered by progressives, Breyer’s votes have made possible the Court’s curbing the death penalty, striking down restrictions on the availability of abortions, upholding affirmative action in university admissions policies, establishing the constitutional rights of gay persons to marry, and declaring that the Environmental Protection Agency has authority to regulate greenhouse gas to curb climate change.

But any such simple classification of Justice Breyer as a “liberal” does not remotely do the Justice justice. Justice Breyer is much better understood as the Court’s residential intellectual — what was once described in more gendered times “a man of letters.” Breyer is more law professor than lawyer and more pragmatist than activist. His eighty-three years understate the generational difference between Breyer and his colleagues on the bench, whose median age is sixty-six and whose youngest member is thirty-three years his junior. Justice Breyer is a throwback to a nineteenth century Justice with little in common in manner, temperament or style to his new millennium colleagues.

Breyer’s chambers at the Court provides the picture that speaks louder than any words. His chambers is unlike any other. The massive book shelves that line its walls are overflowing with ancient, dusty tomes, reminiscent of the early seventeenth century Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford where Breyer studied as a Marshall Scholar after college. Much of Breyer’s collection is in French, though one would not be surprised to learn that many of the books are written in ancient Latin or Greek. Antique prints hang high above on the walls.

For Breyer’s young law clerks, what most likely springs to mind upon first entering Breyer’s chambers is they have somehow landed in the office of Dumbledore — Hogwarts celebrated Headmaster in the Harry Potter series they all read as young children. It is no mere happenstance that Breyer is one of the few Americans, since Thomas Jefferson, admitted to France’s Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques. Or that he serves as chair of the jury that selects the prestigious international Pritzer Architecture Prize.

What is even more striking about Justice Breyer is that such a highly erudite scholar is at bottom the Court’s most pragmatic Justice. He is the first of his colleagues to eschew overarching jurisprudential philosophies in favor of practical, commonsense solutions consonant with basic notions of social justice. His votes and opinions over the past twenty-eight years underscore the Justice’s belief in courts not so much as lawmakers but as problem solvers. Although Breyer plainly revels in the intellectual feast presented by the Court’s work, his actual decision making in individual cases is far more practical than philosophical.

A former law professor, Justice Breyer’s professorial bent has been most evident during the Court’s oral arguments. He never displayed former Justice Scalia’s penchant for launching an avalanche of questions designed to do no less than destroy, while often mocking, the legal arguments he opposed. Nor could Breyer, like former Justice John Paul Stevens pack into the fewest words an unanticipated zinger that, notwithstanding Stevens’ unfailing politeness, held the potential to completely unravel an arguing attorney’s case.

Breyer’s unique signature at oral argument — which challenged and often befuddled lawyers appearing before the Bench — was the sheer length of his questions. Like a law professor teaching a large law school class, Breyer would make invariably make long-winded statements, many pages long in the Courts official transcripts, only then to stop abruptly and elliptically ask something like “Well, what do you think?” Sometimes that question would never even be formally stated and the advocate would accordingly have to be listening to the Justice’s every word, knowing that at any second he might end with a slight inflection in his voice that approximated an implicit question mark.

The median number of total words spoken by a Justice in asking questions during an oral argument in recent decades has been as low as 400 and no more than 500 words. Justice Breyer, by contrast, has spoken almost twice that — approaching 900 words per argument. His closest competitor was, not surprisingly, Justice Scalia, who asked the most questions. But even Scalia’s total words spoken per argument were far less than Breyer’s, topping off at only about 660.

The best Supreme Court advocates learned, however, to welcome Justice Breyer’s questions precisely because they were so differently pitched from those of his colleagues. Breyer’s clear purpose was to explain (at length) his current thinking about the case and then allow the advocate to respond. His goal has not been to trap the lawyer into making a concession or otherwise expose a weakness in the lawyer’s case. It has instead been to allow the lawyer to learn what Justice Breyer was thinking so the lawyer could let Breyer in turn learn if there were flaws in the Justice’s own, tentative legal analysis. In short, the questions were designed to ensure the best possible judicial decision making.

Finally, Breyer’s striking pragmatism should not be mistaken for a lack of passion, even though his reported “bloodlessness” torpedoed his prospects for the Court when President Clinton first considered him in June 1993 and picked Ruth Bader Ginsburg instead. His decades of service on the Court make clear his deep commitment to social justice and the fundamental role of the judiciary in its pursuit. He makes that philosophy clear in both his judicial opinions and in his writings outside of the Court, especially his 2005 book Active Liberty, in which the Justice contends that judges should not merely attend to the need to ensure that individuals are free from governmental coercion but also ensure they enjoy freedom to participate fully in government itself, including the right to vote.

The Justice’s passion for social justice, however, may be best reflected in the number of times he has chosen to read his dissent from a Court ruling from the Bench immediately after the Justice who has written the majority opinion of the Court has summarized that ruling. An oral dissent is rarely done and is intended to underscore the depth of the dissenting Justice’s disagreement with the majority and concern that the Court has gone astray.

Justice Breyer, by his pragmatic nature often reflected in a willingness to compromise, is likely the last Justice one would expect to read an oral dissent from the Bench. It is instead the kind of symbolic, highly public gesture one might fairly anticipate would be embraced by a liberal icon like Justice Ginsburg or her conservative counterpart Justice Scalia. Certainly, neither shied away from making clear what they perceived as flaws in a majority ruling with which they disagreed. But, in fact, Justice Breyer read more oral dissents from the Bench (twenty-two) during his tenure than either Ginsburg or Scalia, during their service together, even including the eight years Scalia was on the Bench before Breyer joined the Court.

At his confirmation hearing in 1994, Justice Breyer made a promise to the American people: “I will work hard. I will listen. I will try to interpret the law carefully, in accordance with its basic purposes.” Justice Breyer has served this nation well. And, his announced resignation deserves far more than a collective sigh of relief. He has earned the nation’s enormous gratitude for a life dedicated to service and justice.