“Just Mercy,” the film based on the memoir of the same name by Harvard Law graduate Bryan Stevenson, ends with a sobering statistic: For every nine people executed in this country, one person on death row has been exonerated.

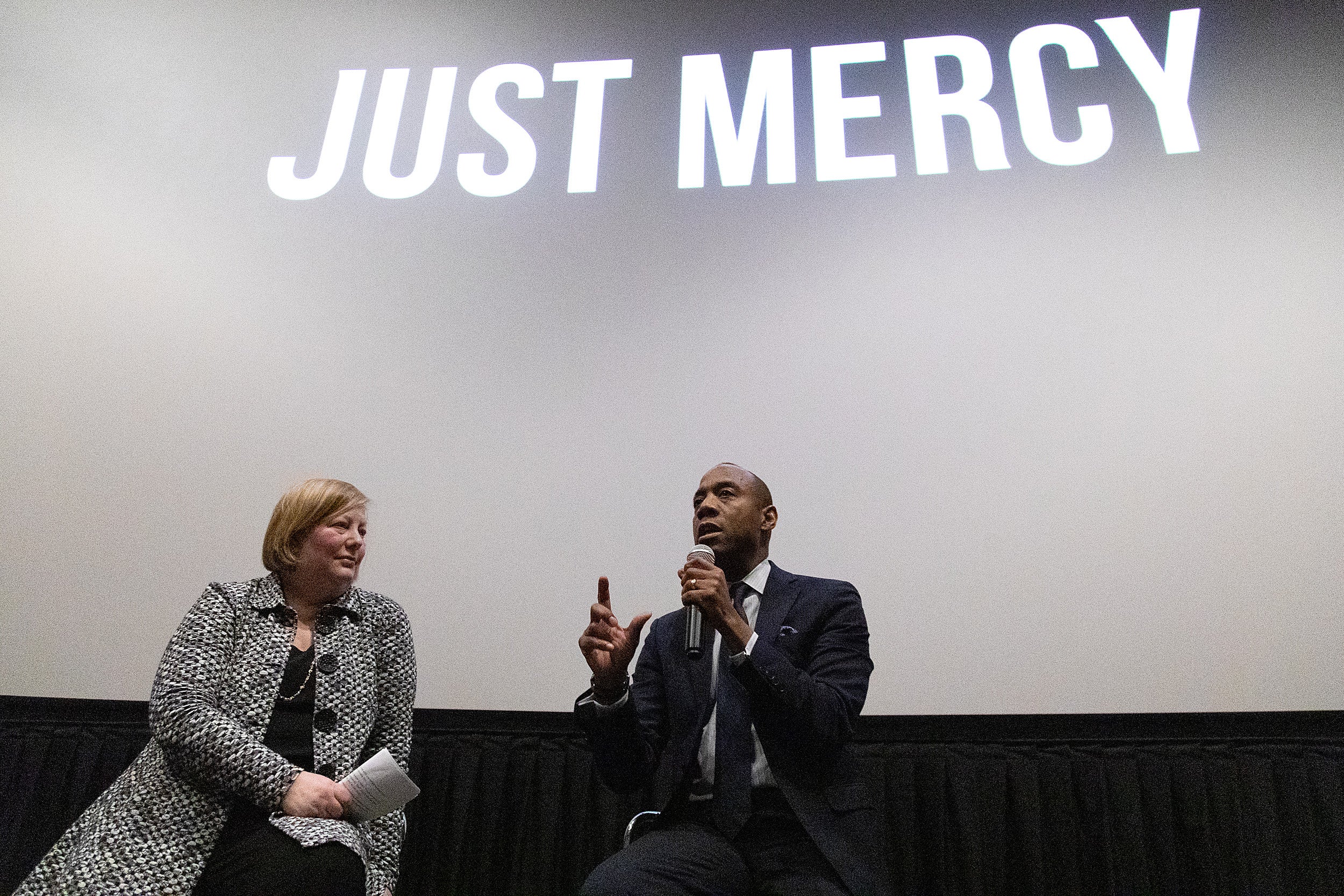

Yet, at a talk in Boston following a recent screening of the film — which stars Michael B. Jordan as a young Stevenson, M.P.P./J.D. ’85, working to free innocent death row inmate Walter McMillian, played by Jamie Foxx — Harvard Law School Professor Carol Steiker noted that makes the United States No. 1 in a problematic category.

“We remain today the only developed Western democracy that continues to retain the death penalty,” said Steiker, who directs the Criminal Justice Policy Program at the Law School and has written extensively on capital punishment. She called the U.S. practice something of a “historical accident” in light of the Supreme Court’s decision to declare it unconstitutional in 1972 because governing statutes “gave sentencers too much discretion that yielded arbitrary and discriminatory results.”

Blowback from the court of public opinion, a crime wave, and the administrations of two Republican presidents who appointed five justices to the court soon led to another pendulum swing. Four years later, the “American death penalty was back in business with a vengeance, as we might say. And for the next 25 years — the 25 years that included the story of Walter McMillian’s conviction and death sentence — American death sentences soared,” said Steiker. “So from 1976 to about 2000, the U.S. quickly went to being one of the world’s leading executors every year.”

But then things changed again. Beginning in 2000, the death penalty began a “free fall” spurred by the use of DNA evidence, said Steiker. “The public discovered that in fact many people, not just Walter McMillian, had been tried and wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death for crimes that they didn’t commit … That fact, more than anything else, has moved the views of many people in the American public against the death penalty.”

Thirty states still have the death penalty, but its use is at record lows. According to a report by the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center, 2018 marked the fourth consecutive year with fewer than 30 executions and 50 death sentences, reflecting a long-term decline of capital punishment.

The film follows Stevenson’s earliest days with the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama, and his struggles to fight for McMillian in the face of racism, intimidation, and malfeasance. Stevenson joined the nonprofit organization that counsels those who have been illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced, or abused in state jails and prisons, those unable to pay for effective representation, and those who have been denied a fair trial, in 1989, a year after he met McMillian. Stevenson proved that prosecution witnesses had been pressured to lie on the stand, and McMillian’s conviction was overturned and he was released in 1993, after six years on death row for a crime he had not committed.

But not all of Stevenson’s clients are innocent. In the movie, he also fights for the life of Herbert Richardson, a Vietnam veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder who was charged with murder after planting a bomb on the porch of a woman who had broken up with him. Richardson was executed in 1989. Teaching other lawyers “how to advocate on behalf of guilty defendants, how to advocate for their lives, how to put on what’s called a mitigating case, how to basically show a jury … the humanity of a person, about how a person is more than the worst thing they have ever done, and how to plead to a jury for mercy, for just mercy,” is another of Stevenson’s lasting legacies, said Steiker.

“The eloquence of [Stevenson’s] example is that hope is morally chosen, not empirically demonstrated. We have to choose to be hopeful, we have to choose to believe.”

— Cornell Williams Brooks

Cornell Williams Brooks, who took part in the discussion with Steiker, said the film should “be studied like a casebook and a point of meditation.”

Brooks, professor of the practice of public leadership and social justice at Harvard Kennedy School, sees lessons for aspiring lawyers and policymakers in Stevenson’s embrace of proximity, the notion of getting as close as possible to the suffering and despair of those in need. “Bryan doesn’t interview his client from across the room; he is proximate, he is close, he is in touch with his client,” said Brooks. And he is in touch with his client’s “story as a human being.”

Brooks also highlighted the importance of storytelling in the film and the ways in which Stevenson brings multiple voices to McMillian’s defense, adding a “moral gravitas” to the narrative and allowing his “humanity to come to the fore.”

For Brooks, the film also delivers on hope.

“The eloquence of [Stevenson’s] example is that hope is morally chosen, not empirically demonstrated,” Brooks said. “We have to choose to be hopeful, we have to choose to believe.”

Steiker and Brooks urged students to think about the broad range of approaches available to them to work against the death penalty, including arguing for someone’s innocence and humanity, the skyrocketing costs from administering the death penalty, and the idea of forming coalitions with unlikely advocates such as prison wardens, guards, and police officers.

“Lots of things appeal to different people,” said Steiker. “You’ve got to study your target audience and you have to know what’s going to appeal to them.”

More broadly, Brooks encouraged his listeners to consider a historical framing when confronting institutional racism in the criminal justice system and beyond. “Talking about lynching, talking about the new Jim Crow, talking about stop-and-frisk being a digitized 21st-century version of slave captures and slave patrollers” is key, he said. “Simply telling the truth about racism [is] necessary but not always sufficient.”

“It’s time for us to take a step back … it’s a question of reflecting on what our moral values are as a society,” said Lina Iddisah, who is pursuing a master’s degree in public policy at the Kennedy School.

Stevenson has pushed the historical narrative forward in Alabama with his most recent efforts, including the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, and the nearby National Memorial for Peace and Justice dedicated to thousands of victims of racial injustice and lynching. Though not in attendance for the talk, which was sponsored by the Law School and Kennedy School, he made a brief appearance, introducing the film in a three-minute video.

“I think we are living at a time when we have to be resolute in combatting the politics of fear and anger,” said Stevenson. “Fear and anger is what gave rise to the wrongful conviction of William McMillian. It’s what allowed institutions to turn their back on fair and just treatment. We are living at a time where in too many communities our system treats you better if you are rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent. There is a presumption of dangerousness and guilt that gets assigned to some people — black people, brown people, people who are different — and to combat this we need a community of people who are just willing to talk about what justice requires.”