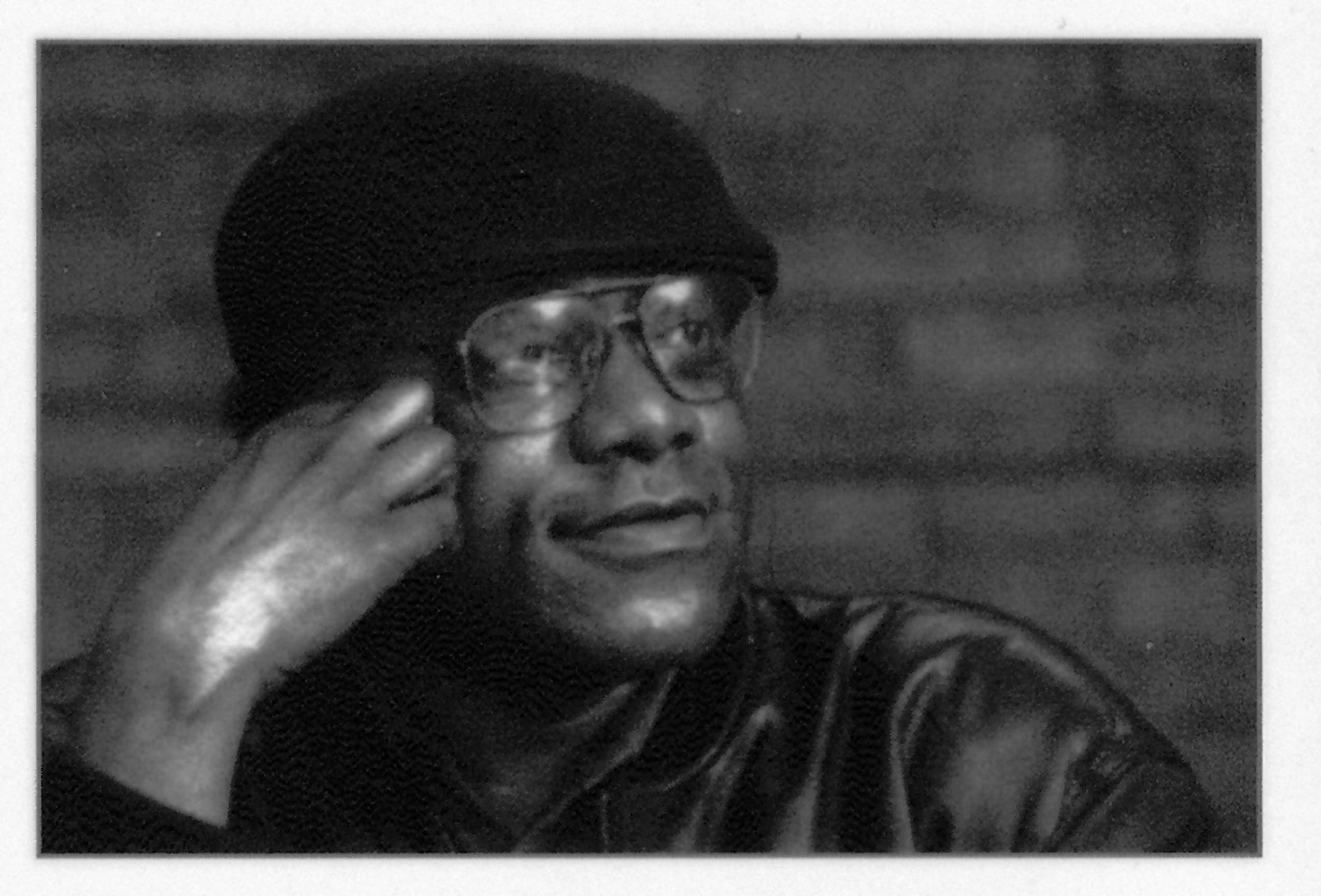

James Alan McPherson ’68 grew up in poverty in segregated Georgia, and went on to write short fiction and essays that deftly explore race, class and community and what it means to be human. He was the first black author to receive the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

McPherson graduated from Morris Brown College, a traditionally black institution in Atlanta. While he was a student at HLS, he wrote for the Record, and to make ends meet, worked as a janitor in a Cambridge apartment building, where he found “the solitude, and the encouragement, to begin writing seriously.”

Before he graduated, his short story “Gold Coast” about the relationship between a black aspiring writer supporting himself as a janitor and his older white supervisor was published in the Atlantic and launched his literary career.

During the following decade, his fiction and essays appeared in numerous journals and magazines. In 1970, for an issue of The Atlantic Monthly, McPherson did a cover interview with the novelist Ralph Ellison, who became a mentor and friend. McPherson has been called one of the “literary heirs” of Ellison.

I believe that if one can experience diversity, touch a variety of its people, laugh at its craziness, distill wisdom from its tragedies, and attempt to synthesize all this inside oneself without going crazy one will have earned the right to call oneself ‘citizen of the United States’.

James Mcpherson

In 1978, McPherson won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction for his collection “Elbow Room.” At the time, The New York Times Book Review wrote of McPherson, “He was able to look beneath skin color and clichés of attitude into the hearts of his characters. … a fairly rare ability in American fiction where even the most telling kind of perception seldom seems able to pass an invisible color line.”

The collection has continued to resonate. In 2004, the American fiction writer ZZ Packer cited “Elbow Room” among the books that had “changed” her. “It wasn’t trying to represent black America in a particular way,” Packer said in an interview with the Sun Herald of Sydney. “It’s a book of short stories about the lives of African-Americans and it’s very intimate, although it opens out and gives you a greater sense of what it means to be human.”

McPherson was not someone who sought the limelight. The Chicago Tribune once described him as “only slightly more gregarious than J.D. Salinger,” according to an obituary for McPherson in The Washington Post.

After winning the Pulitzer, he left the University of Virginia and joined the faculty at the Iowa Writers workshop, where he was a beloved teacher. He went on to receive many other honors including a MacArthur fellowship in 1981, the first year the “genius” awards were granted. By then he was divorced from his wife, and he said he used the money mostly for airfare to visit his daughter.

McPherson appeared again in the literary scene with the publication of his memoir “Crabcakes” in 1998. The book focused on his relationship with an elderly couple in Baltimore for whom he bought a house, when they faced eviction. It also explored his stay in Japan, where, he wrote, he went to lay down “the burden carried by all black Americans, especially the males.” Two years later his published his final book, “A Region Not Home: Reflections from Exile.”

McPherson is survived by his daughter and son as well as a sister and brother.

Although McPherson never practiced law, in his essays and fiction he came back to the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment he had studied in Paul Freund’s constitutional law class and to the principles of diversity argued for by Albion W. Tourgée in his brief in 1896 in Plessy v. Ferguson.

“What he was proposing in 1896, I think, was that each United States citizen would attempt to approximate the ideals of the nation, be on at least conversant terms with all its diversity, carry the mainstream of the culture inside himself,” McPherson wrote in an essay “On Becoming An American Writer” published in The Atlantic in 1978. “As an American, by trying to wear these clothes he would be a synthesis of high and low, black and white, city and country, provincial and universal. If he could live with these contradictions, he would be simply a representative American.”

“I believe that if one can experience diversity, touch a variety of its people, laugh at its craziness, distill wisdom from its tragedies, and attempt to synthesize all this inside oneself without going crazy,” he wrote, according to an obituary in The New York Times “one will have earned the right to call oneself ‘citizen of the United States.’”