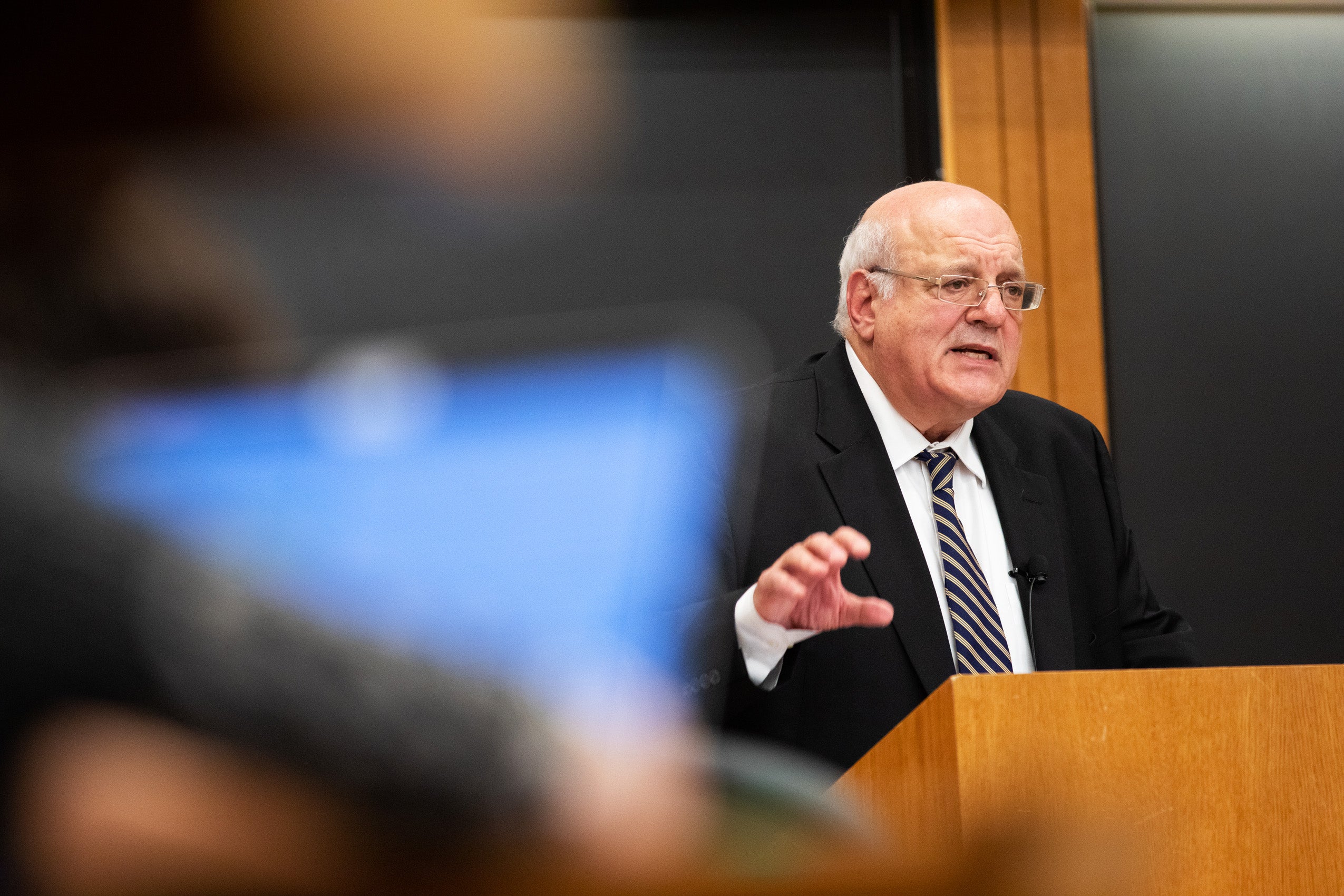

In recent years, there has been much talk about how social-media intrusions—bots, trolls and propaganda—affected the last U.S. presidential election, and may affect the next one. But this is increasingly a worldwide phenomenon, and on Oct. 23 at Harvard Law School, Deputy Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Israel Hanan Melcer described how his country has dealt with it.

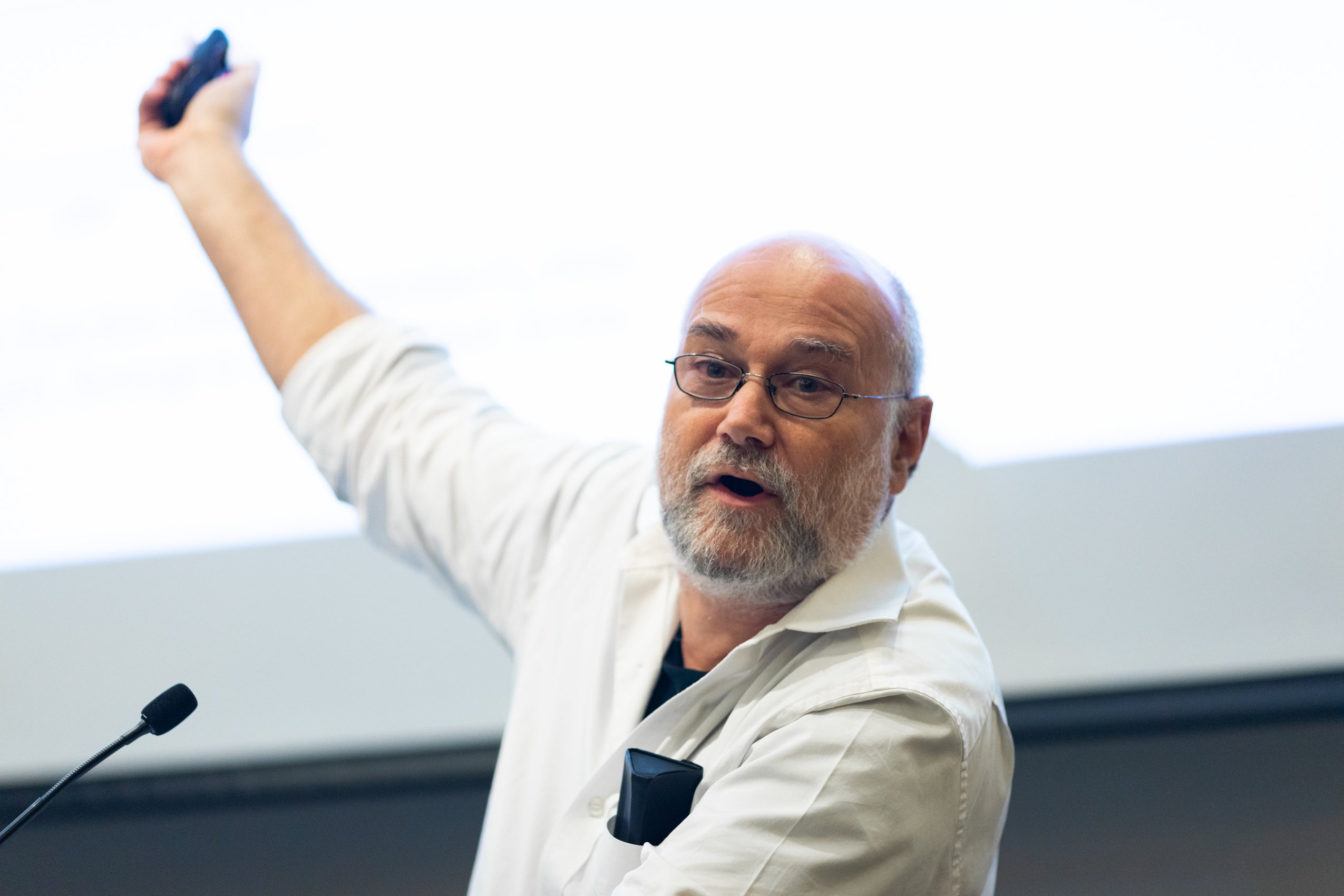

Israel’s cyberattacks didn’t come from Russia or another outside country, but from political parties spreading propaganda against each other. Moderated by Harvard Law School Professor Yochai Benkler ’94 and sponsored by the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, the talk outlined measures the Israeli Supreme Court took to shut down deceptive election posts. As Benkler, the author of “Network Propaganda Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics” noted, “(Israel) saw everything we saw in our last election cycle, and much that we will likely see in the next two years.”

Melcer began by noting that the nature of his work changed during Israel’s two elections in 2019: For the first time, working against propaganda and cyberattacks took up a substantial part of his time as election committee chairman. “This was something that hadn’t occurred in the past, and it was a new challenge. At night I sat with security and intelligence agencies, and at first I couldn’t even tell anyone I was working on it.”

He outlined a few specific instances of cyberattacks, which at times put him in direct conflict with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party. Israel, he noted, has a propaganda law dating from 1959 that forbids anonymous election advertising; an ad’s sponsor needs to be clearly visible. During the two 2019 elections, the question was whether this law could be applied to modern social media.

He threatened to take away immunity from the cell companies. And he ended up enjoining the sitting Prime Minister from using a chatbot. That’s all worth keeping in mind.

Yochai Benkler

Just when the court was pondering this question, he said, a billboard appeared that targeted four journalists who had been critical of the government, and the same ad was posted on Facebook. Both were anonymous, and the connection to the 1959 law was stronger since the ad had originated on a billboard. Melcer noted that Israeli law also allows referring to ancient Jewish law when there is no clear modern precedent, so he also took this avenue. “I was afraid that the party would attack my decision, so I covered myself with all alternatives.”

He also took a step that was highly ambitious by U.S. standards: He met with Facebook executives and pressured them to drop the anonymous ads. “I called them for meetings and they came over from the United States. At first they were very polite, but not responsive. So I told them there was another alternative: We could go by the legal path, but I don’t know if that is advisable from their point of view. After that, about 70 percent of anonymous material on their networks went down.”

In two related cases, he even went up against cell phone carriers. During the first of two Israeli elections in 2019, one political party distributed a cell-phone poll to thousands of customers. Recipients were polled on how they planned to vote, but one of the sponsor party’s main rivals was not listed among the choices. “By not including that party in their poll, they gave the impression that the party was not past the threshold percentage of the vote [which it was]. We issued an injunction and the company was not allowed to distribute messages without telling who stood behind the poll.” The irony, he noted, was that the sponsor was a political party whose claim to fame was a “clean” way of doing politics.

In the most recent case Melcer cited, the court went directly up against Prime Minister Netanyahu. Israel has a law against circulating polls within three days of an election, and Netanyahu’s Likud party violated that in the most recent election. They used a chatbot on Facebook Messenger to cite dubious poll results claiming “that the liberals and leftists, as they called them, were going to win if Likud supporters didn’t go to the polls.” The court issued an injunction against both Facebook and the party, and Likud came up with a novel defense: Because they had in fact made up the statistics, they argued that a fake poll shouldn’t be subject to the same restrictions as a real one.

When that didn’t work, Likud offered to pay contempt-of-court fines if the poll remained up; this too was rejected. The bot was reinstated after negotiation between the court, Likud and Facebook, but the illegal material was removed and the bot was disabled during nine crucial pre-election hours.

At this point Benkler underlined the significance of Melcer’s work. “He threatened to take away immunity from the cell companies. And he ended up enjoining the sitting prime minister from using a chatbot. That’s all worth keeping in mind.” Melcer agreed that aggressive measures were called for. “You have to make it clear that the final decision is not theirs [the sitting government’s or the social media company’s]. And if an injunction is issued against them, they understand it even better.”