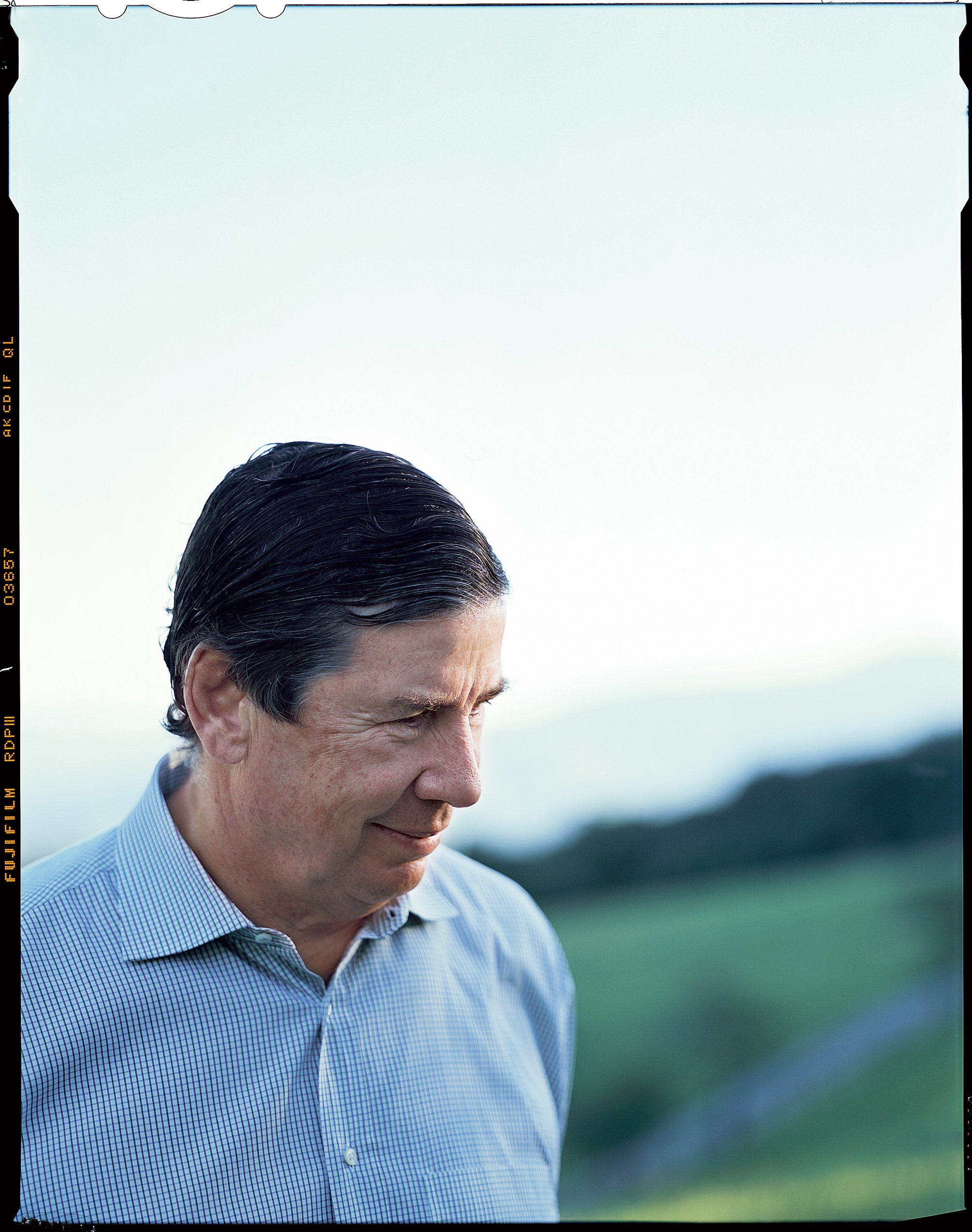

Frederick P. Hitz ’64 Writes the Book on the Fact and Fiction of Espionage

In his recent book, “The Great Game: The Myth and Reality of Espionage,” Frederick P. Hitz ’64 gives credence to the saying that truth can be stranger than fiction. A veteran of the CIA who worked at the agency on and off for more than 30 years, Hitz offers an insider’s perspective on the real-life cases of spies such as Kim Philby and Aldrich Ames, contrasting their exploits with the spy fiction of John le Carré, Graham Greene and others.

Fiction has the advantage when it comes to gadgetry, Hitz concedes, but it can’t completely encompass the psychological complexity of human motivation. Robert Hanssen, for example, was an FBI agent who lived frugally throughout the 15-year period he spied for the Russians. A conservative Catholic with six children, he lavished gifts on a stripper and was politically and philosophically opposed to Communism. “It’s that decoupling of reality from a spy’s beliefs that’s so difficult to portray in fiction,” Hitz said.

In his first post at the CIA, Hitz worked as a spy himself, keeping tabs on Soviet and Chinese influence in the newly independent nations of West Africa. He tells of swimming with his wife in Togo’s capital port of Lomé as a way to meet the Soviet ambassador and his entourage. “There weren’t many areas for recreation, but that was one place where people gathered,” he recalled. “We were making our way through grapefruit rinds and a slick of diesel fuel. It’s pretty absurd when you think of the lengths one goes to in order to pursue the target. But we did it, and we were successful.”

The war against terrorism has changed all the old rules of espionage, Hitz says. “Spies today operate in an environment where there is no structure, no official diplomatic entity to penetrate–these are renegade groups.” One fact that remains unchanged, he observes, is the need for a deep knowledge of the language and culture in which one operates. But finding people with the necessary background is no easy task.

“Out of the 1.5 million college graduates in 2003, only 22 majored in Arabic,” said Hitz, who is currently a lecturer at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. “We’re not getting it done in terms of languages.”

In addition to serving as a spy, Hitz worked in the departments of State, Defense and Energy before returning to the CIA from 1978 to 1982 as legislative counsel to the director of central intelligence and deputy chief of operations for Europe. In the wake of the Iran-Contra scandal, President George H.W. Bush appointed him inspector general of the agency in 1990 to investigate allegations that it had participated in drug trafficking in Central America.

“I was someone who knew the business of espionage but had not been involved in more recent activities,” Hitz noted. While he found no direct involvement, his report criticized the lack of guidelines provided to field operatives in the event that they encountered illegal activity. “The CIA had become a bureaucracy at that point,” he recalled. “Any new leader is going to have to work very hard to curb that tendency.”

Despite these concerns–and public criticism that the CIA has become bloated and self-satisfied–Hitz believes that the agency’s staff members are motivated and hardworking, as depicted in the 9/11 Commission’s report. “The question is,” he asked, “are they being led properly and are the skills being assembled to meet the challenges that currently exist?” It’s leadership, he says, combined with expertise in language and culture, that’s needed in today’s great game.