In 2010, France adopted a law banning full-face coverings in public. Opposed by several human rights organizations, the law was challenged quickly in the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and later before the United Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC).

In bringing the cases, the applicants charged that the law discriminated against them indirectly. On the face of it, the law treated everyone the same, but it had disproportionate effects for Muslim women who wore niqabs. Notably, the ECtHr upheld the law, while the HRC found it to be a violation of human rights.

Cases like these, and differences between approaches, occupied much of the conversation at a recent Harvard Law School Human Rights Program (HRP) workshop focusing on indirect discrimination on the basis of religion.

Gerald Neuman ’80, the J. Sinclair Armstrong Professor of International, Foreign, and Comparative Law, convened the workshop on Saturday, April 18. HRP hosted the workshop in cooperation with the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, the Columbia Law School Human Rights Institute, and the Harvard Human Rights Journal.

What is the Right against Discriminatory Impact Based on Religion?

The pursuit of equality in international human rights law includes both prohibitions of intentional discrimination and prohibitions of practices with discriminatory impact. The latter category, often designated as “indirect discrimination,” raises numerous questions that have not been fully explored. One important subset of those questions relates to indirect discrimination on the basis of religion.

Gerald L. Neuman Symposium Introduction: Harvard Human Rights Journal »

Neuman’s interest in comparative approaches to indirect discrimination was first sparked by his experience as a member of the HRC from 2011 to 2014.

“It was clear to me then that the committee had a well-established general concept of indirect discrimination but that members disagreed on how it should be applied concretely,” he said. “That made me alert to similar uncertainties in other treaty bodies and international courts over the following years.”

Neuman, who is also co-director of the HRP, has been writing on the comparative constitutional law of discrimination and comparative approaches to freedom of religion since the 1990s. The April 2020 workshop is the first in a series on indirect discrimination and its intersection with other factors.

Participants included current and former members of the HRC, such as HRC Vice-Chair Yuval Shany, who is also Hersch Lauterpacht Chair in Public International Law at Hebrew University. Members of the Harvard community and experts from civil society were also in attendance, including Victor Madrigal-Borloz, the U.N. independent expert on sexual orientation and gender identity and HRP’s Eleanor Roosevelt Senior Visiting Researcher; Daniel Mach, director of the ACLU Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief; and Anna Batalla, human rights officer at the petitions and inquiries section of the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

Victor Madrigal Borloz, UN Independent Expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and HRP’s Eleanor Roosevelt Senior Visiting Researcher, attended in advance of a future thematic report, which will focus on religion and sexual orientation and gender identity.

“My hope is that these workshops will provide a forum for exploring the range of indirect discrimination and approaches to regulating it, leading to proposals for how human rights bodies could better protect subordinated groups while allowing justifiable government policies,” Neuman said.

Banning the Full-Face Veil

What is, or should be, the relationship between claims of violations of the right to manifest one’s religion as a result of a generally applicable law or policy, and claims of indirect discrimination on grounds of religion?

International human rights law strives for equality broadly, but antidiscrimination law plays out differently depending on the jurisdiction and the court. Over the course of the workshop, participants considered several cases from European, U.S., and international law and compared them in theory and practice.

Prior to the event, several participants also submitted essays to the Harvard Human Rights Journal, which published them in an online symposia section. Contributions from Christopher McCrudden, William W. Cook Global Law Professor at Michigan Law, and Sarah Cleveland, Louis B. Henkin Professor of Human and Constitutional Rights at Columbia Law School, helped frame the day.

A European perspective

In this brief note on legal measures addressing indirect religious discrimination, I draw from the experience of the development and use of indirect religious discrimination in several European jurisdictions: the United Kingdom (including the somewhat different legal position in Northern Ireland), the European Union, and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECtHR).

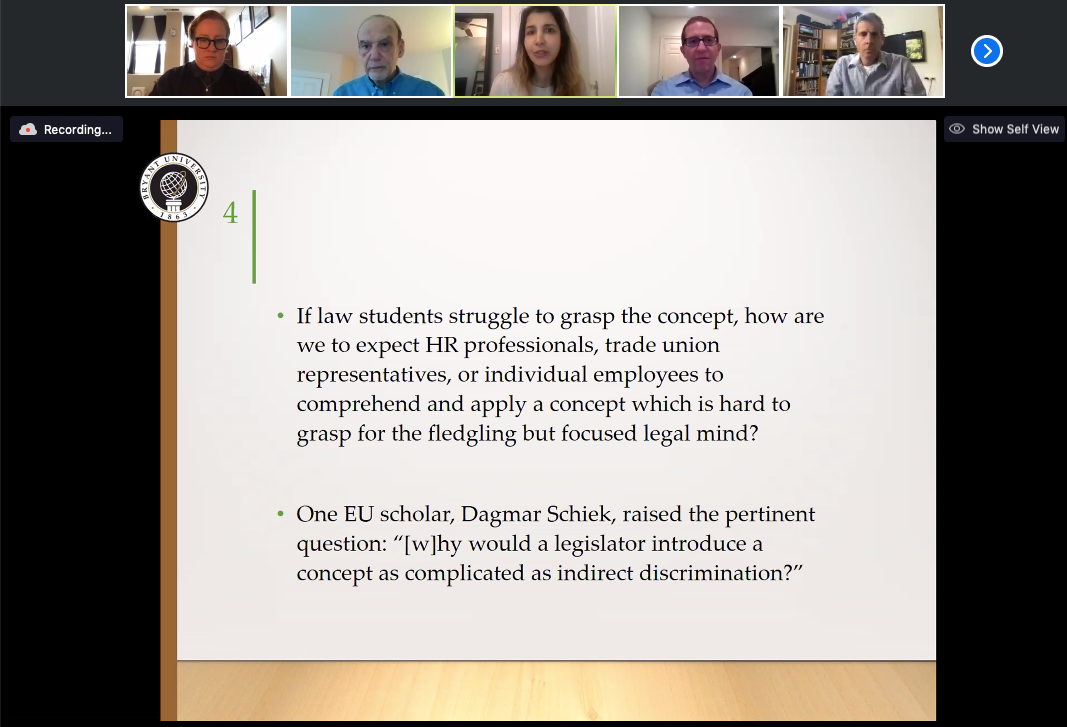

In one essay on employment, religion, and indirect discrimination presented early in the workshop, Katayoun Alidadi LL.M. ’05, assistant professor of legal studies at Bryant University, called indirect discrimination confusing for lawyers, much less the members of civil society who must comply with antidiscrimination law in an employment setting.

“How do we expect H.R. [human resources] professionals to comprehend what even the fledging legal mind cannot?,” she asked. In the European Union, she concluded, identifying and pursuing legal action on the basis of indirect discrimination has been “disappointing.” In her presentation, she argued that a more inclusive approach would be to address such cases by ensuring “reasonable accommodation” as is done in the U.S.

Adjudicating Religion

The right to religious freedom and the right against religious discrimination should be seen as two distinct human rights, with different normative purposes. I have argued elsewhere—with Dr. Jane Norton—that religious freedom is best understood as protecting our interest in our decisional autonomy in matters of religious adherence (and non-adherence). The right against religious discrimination, on the other hand, is a sub-species of the general right against discrimination on protected grounds, and is best understood as protecting our interest in the unsaddled membership of our religious group (akin to our race or tribe).

Tarun Khaitan, professor of public law & legal theory and the Hackney Fellow in Law at Wadham College, Oxford University, Future Fellow at the University of Melbourne, and visiting Global Professor of Law at New York University Law School, presented his essay, “Adjucating Religion,” during the course of the workshop.

“I came away [from the workshop] even more convinced than ever that the concepts of religious freedom and religious non-discrimination need to be distinguished clearly,” he said. He added that the workshop demonstrated a further “need to explore manageable doctrinal standards for uncovering pretextual discrimination by the state.” He believes it is possible for there to be intent in indirect discrimination cases, and whether or not someone pursues legal action on the basis of direct or indirect discrimination or religious freedom or freedom from discrimination on the basis of religion is largely a matter of legal strategy.

Khaitan, who spoke about how difficult it is for courts to assess religious discrimination when individual belief systems and practices are so personal, also identified algorithmic discrimination and implicit bias as emerging interests in discrimination law more broadly.

Many participants agreed that the issue of indirect discrimination required further parsing. Reflecting on the group’s discussion on the French law banning full-face coverings, for instance, Neuman noted that human rights bodies confront a dilemma when states make sophisticated efforts to conceal discriminatory motives.

“Even the Human Rights Committee, which took the step of finding the law discriminatory, avoided clear description of the violation as resting on intentional discrimination or indirect discrimination,” he said.

“There are still unanswered questions about how best to analyze laws that unintentionally restrict a practice favored by a small subset within a minority religion, whether by treating them as limiting the religious freedom of the relevant believers, or by examining them as possible instances of discrimination,” Neuman said.

Next fall, Neuman plans to convene a workshop on indirect discrimination and sexual orientation and gender identity.