Does ChatGPT spell the end of English Lit 101, or an improvement to it? Could DALL-E make art class irrelevant, or more important than ever?

Since the 2022 debut of ChatGPT, a text generator powered by a large language model that uses artificial intelligence to generate responses, the world has been both giddy and apprehensive about the future of the technology. Generative AI tools capable of answering questions, responding to complex prompts, and even generating novel images, music, and prose have led many to fret about the ways in which the nascent tools could change the way we live, work, play — and learn.

Teachers, in particular, have expressed anxiety about how AI might transform education, from facilitating cheating, to preventing students from retaining information or practicing new skills, to introducing bias or misinformation. But while these are valid concerns, says Sarah Newman of metaLAB at Harvard, part of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, she adds that AI might also offer exciting new possibilities for learning, and that students should understand how it works, including the risks it poses.

MetaLAB’s latest initiative, called the AI Pedagogy Project, aims to demystify artificial intelligence for educators and help them think about how AI tools might be incorporated into their teaching. Newman began the project, which includes tutorials, resources, and live events, after she noticed that her students were increasingly curious about AI technology — an enthusiasm not always matched by their professors.

“One of the things I noticed from fellow educators here at Harvard, but also in conversations with educators elsewhere, was that people coming from non-technical fields seemed very concerned and self-reportedly ill-equipped to address AI,” says Newman, who is director of art and education at metaLAB.

Newman stresses that the project’s main goal is to empower educators who are interested in considering the implications of AI — not to force anyone to adopt it. “We want this to be a starting place, to use it as a way for educators to reflect on their own pedagogy and the goals of their teaching,” she says. “AI tools can also help us reflect on our own disciplines and see them in a new light.”

The project is aimed at all educators, with special attention to those in the liberal arts, Newman says, because of what those disciplines can in turn contribute to AI. “We want to examine not just what AI might teach us about history, but also what history can teach us about AI. Or, for example, where can philosophy contribute when we consider what it means to be human, and ask: What kind of future do we want to create, who is doing the creating, and who will participate in those conversations? How will AI change the way law is read, written, and taught, while the law is, in real time, a means for limiting the power of the very AI technologies that will change how it is practiced?”

“We want to examine not just what AI might teach us about history, but also what history can teach us about AI.”

Sarah Newman

Sebastian Rodriguez, a developer and researcher from the metaLAB team, who first joined the project as a 2023 intern at the Berkman Klein Center, agrees. “The humanities raise these critical questions, and our goal is to help educators facilitate these conversations in their classrooms,” he says. “It’s important for students to consider the potential use cases, risks, and ethical implications of AI before they go out and start their careers. And although our project is framed through a humanistic lens, educators from any field can use and find value in our resources.”

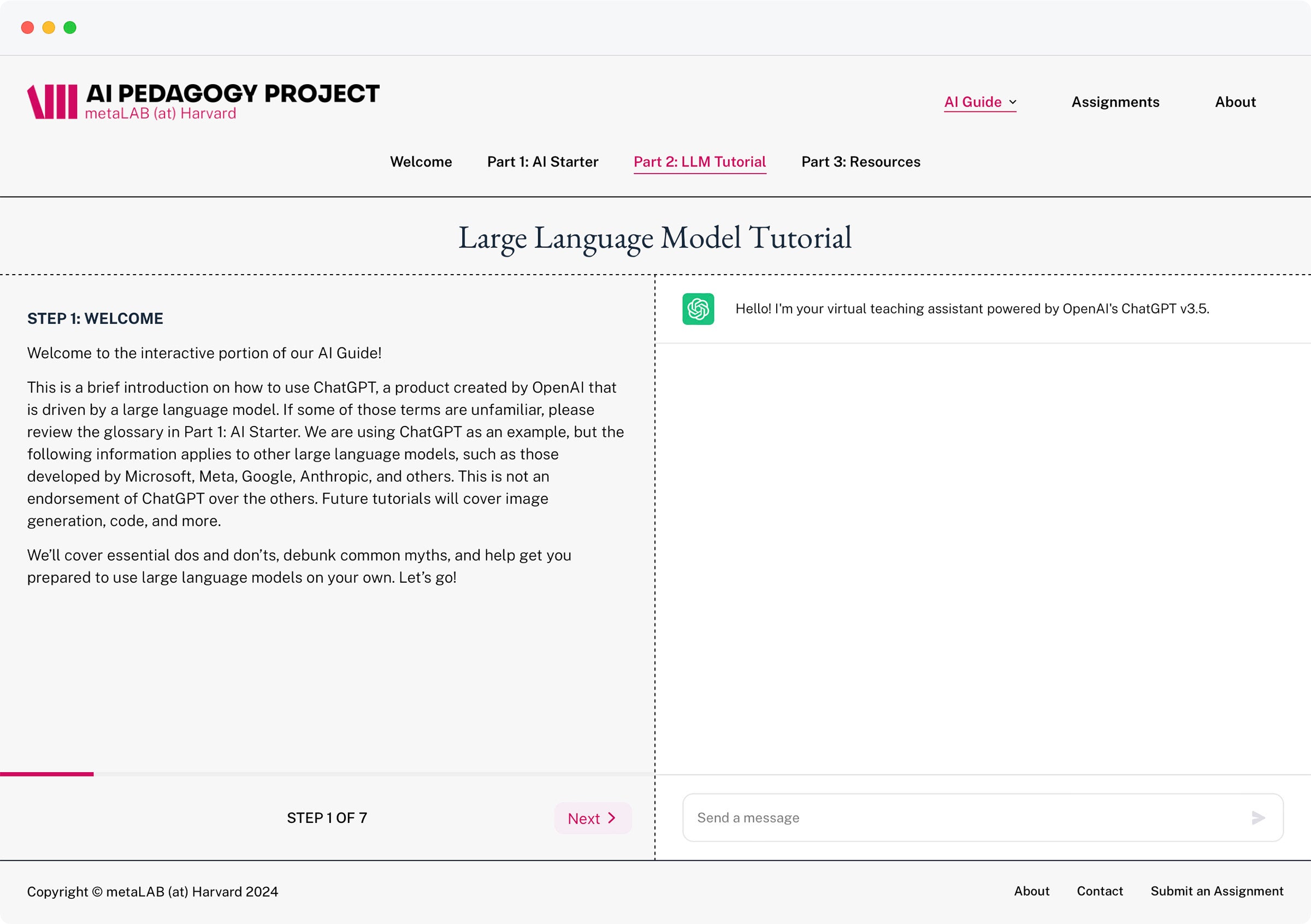

To that end, the AI Pedagogy Project’s website explains — in accessible terms — what AI tools are and how they work. A set of additional resources point teachers to more information about how AI functions, sample codes of conduct for the use of AI in the classroom, and online communities dedicated to discussing the use of AI in education.

The team, which is composed of students and educators, as well as a lineup of terrific advisors, also created an interactive ChatGPT tutorial to walk users through the chatbot’s interface, outlining what it can and cannot do, and offering ideas for how the model might be deployed in everyday lessons. For example, Rodriguez says the tool can be a useful resource to learn more about a topic of interest. “It isn’t always going to be accurate,” he cautions. “But it can give you a good starting place to explore a topic, which you can use to search for other sources and form your own ideas.”

Newman admits that it is hard to predict all of the ways in which educators might use AI. But that’s part of what makes it interesting, she says. “For some people, AI tools are useful in brainstorming or thinking outside the box, because you can get large language models to perform as randomness generators, in a way. For others, they can serve as starting places from which to iterate. Different people learn in different ways, and these tools will serve people differently.”

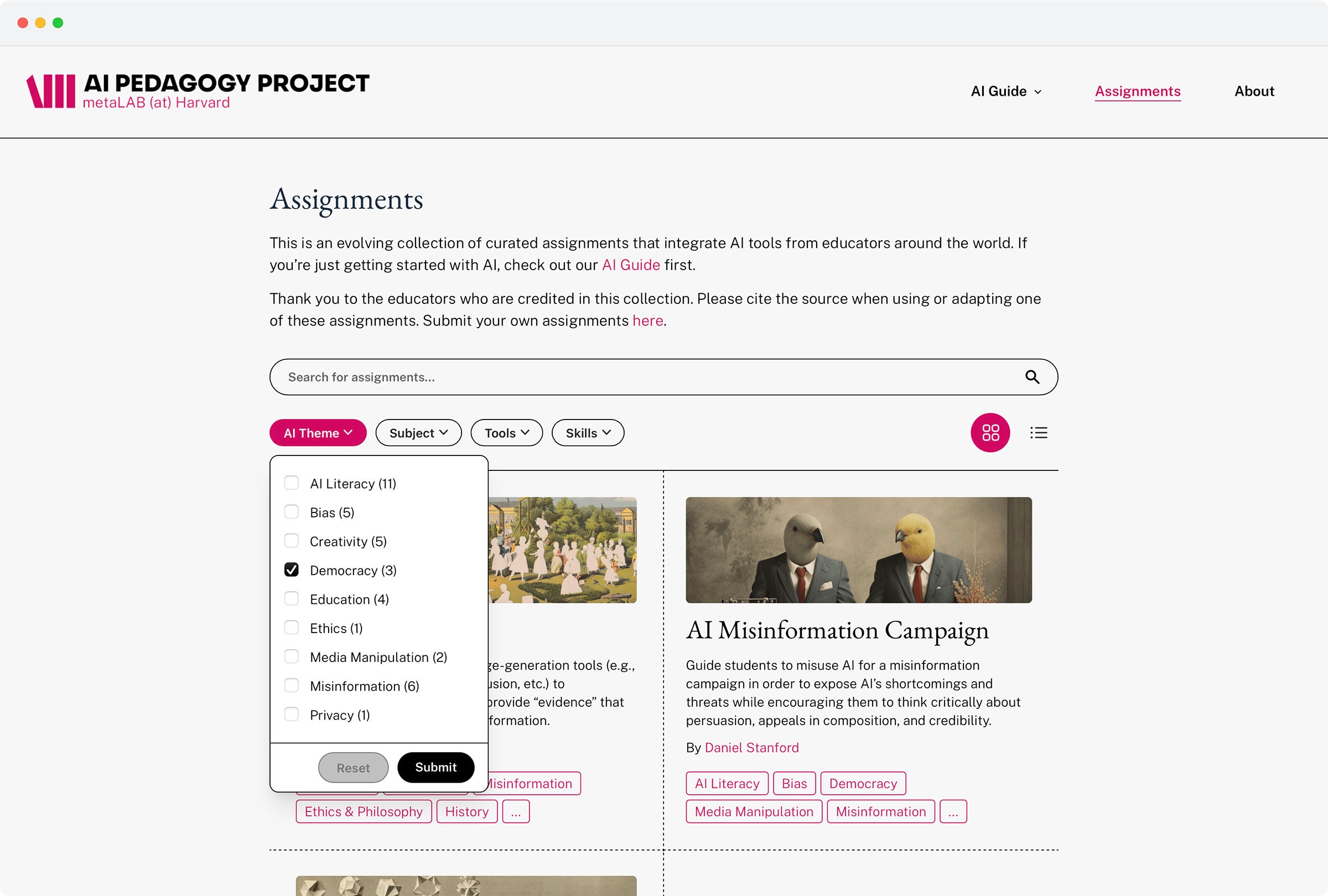

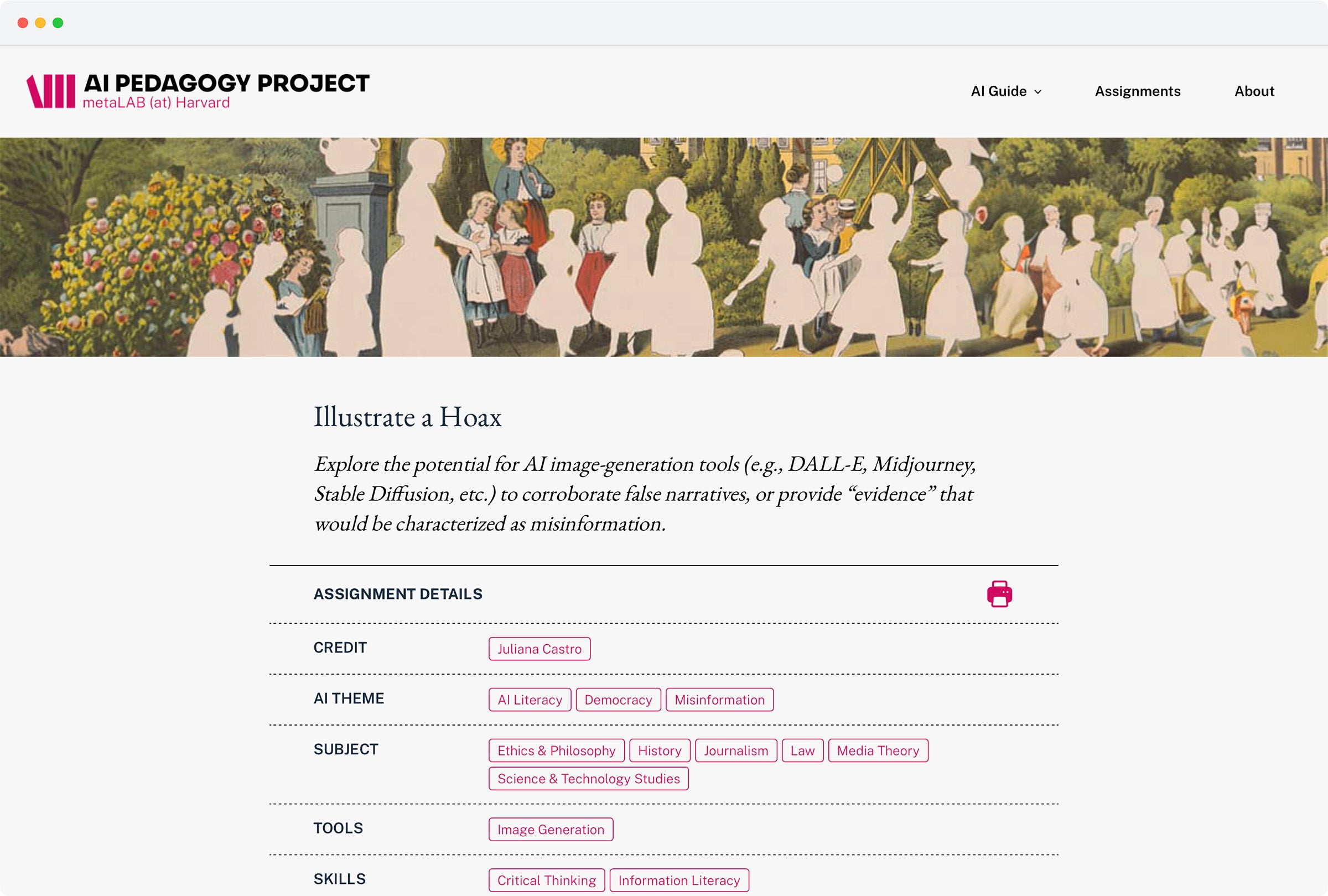

The AI Pedagogy Project’s website also features a growing collection of classroom assignments that integrate AI into a lesson plan or learning module, says Rodriguez. “Our assignments are designed to help students reflect on the capabilities and limitations of AI. Some are really hands-on, having students input a prompt and critically analyze the response. But other assignments are meant to provoke discussion and critical thinking about AI without necessarily using the tools themselves.”

The assignments come from educators across the world who are starting to experiment with AI in the classroom, says Newman. “We wanted to create a searchable repository of assignments, so that educators whose specialty is, say, biomedical ethics or Russian literature, can bring their subject material into dialogue with AI technologies.”

The team hopes that educators come away not only with a better understanding of AI tools, but also where they can fall short.

“A creative and critical approach is really important for us — we’re not just celebrating this stuff,” Newman says. “Any use of it should include a critical lens that considers bias, labor practices (used in training and tuning the models), what are the environmental impacts, media manipulation, and other potential harms.”

Ultimately, says Newman, AI is likely to transform education in unexpected ways — and teachers could be on the forefront of that change. “Education has always evolved alongside technologies,” she says. “The way people now write is different than the way they wrote before there were word processors or typewriters. The way people now learn to spell is different because we have spell checkers. These AI technologies are different, but not so different that we can’t see this as part of a historical evolution of education too.”

The AI Pedagogy Project will hold a virtual workshop for educators and others on February 14. Learn more on the metaLAB website, and visit the AI Pedagogy Project here.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.