The following article by Corydon Ireland appeared in the August 9 issue of the Harvard Gazette.

The rote notes of early U.S. law

In 1812, a Connecticut law student named Samuel Cheever summarized a lecture on “Baron and Feme,” which were the legal terms for husband and wife. Toward the top, in Cheever’s slanted script, is a sentence that seems chilling now: “The husband acquires an absolute right over all the property of the wife in possession, and her right is entirely destroyed.”

Such were the lessons taught 200 years ago to apprentice lawyers, points that are of interest to scholars of legal history or to anyone simply eager for an intimate glimpse into a vanished past.

Cheever’s jottings are among a collection of recently digitized student notebooks from the Litchfield Law School (1784-1833). The original holdings are from the Harvard Law School Library’s historical and special collections: 64 bound volumes of notebooks drafted by 17 students from 1803–1825.

Litchfield is generally regarded as the first formal private law school in the United States. It offered no degrees, and after a program of lectures its students still went on to apprenticeships. But instruction at Litchfield went beyond anything that had come before. The College of William and Mary had offered lectures in law earlier, but they were intended as a part of a general education.

Litchfield’s student body included a surprising number of college graduates. Their notebooks — typically fine copies of class notes — are today scattered throughout university and museum archives. Most are at the Litchfield Historical Society and at Yale Law School, said Karen S. Beck, Harvard Law Library rare books curator and manager of historical and special collections. But Harvard has some too, and now they are available for viewing by anyone online.

Notebooks of great value

Such notebooks are of great value to scholars, something Beck has written about for the Law Library Journal. (Her article also contains a summary of Litchfield’s history and significance.)

“They show the way people thought about the law,” said Beck of the notebooks, “how they learned it, and how they taught it.” Primary sources like these are especially revealing about law training in the early days of the United States, she said. For one, lawyers were struggling with how much English common law to teach, and how much American law.

Central to the Litchfield story is Tapping Reeve (1744-1823), the school’s euphoniously named founder. He was a young lawyer in Litchfield and, like many others, he accepted clerks and apprentices who would perform practical chores and study from books on the side. After the Revolutionary War, their numbers grew so large that Reeve started offering formal lectures, first in his parlor and later in a building on his property. Litchfield became a formal school, with a law library, weekly examinations, and even a moot court. Its nation-scale curriculum drew students from every state, a geographical reach unheard of in that era, even among established colleges.

Reeve was named to the Connecticut Supreme Court in 1798, so he began sharing teaching duties with James Gould, a former student. As the notebooks show, Reeve liked to veer into asides while reading his lectures. Gould, on the other hand, was known for reading his own lectures very slowly, usually twice in the 90 minutes allotted.

Studying at Litchfield required listening to 139 such lectures, which commonly took 14–18 months. After each lecture, students would make fine copies of what they heard. A typical day, as described by one student, involved the morning lecture, an afternoon of copying, an early evening of reading the law, and a late evening of writing.

The typical Litchfield student left with five bound notebooks of 2,500–3,000 pages or more of fervently taken notes. (In her article, Beck quoted from Dante’s “Divine Comedy”: “He listens well who takes notes.”) The resulting notebooks were not ephemera, she added, but leather-bound, encyclopedic references consulted over a lifetime of law practice. Because so many of the volumes were on tidy shelves and in practical use, many survived to find their way into libraries. Such notebooks are still so numerous, with many more yet to be discovered, that in the article Beck called her 60-page bibliography of such holdings “a narrow slice.”

Records indicate that the 64 bound volumes now digitized had been acquired over a century, dating back at least to 1859.

A bridge in teaching law

Litchfield was a bridge, said Beck. On one side was what had been typical legal training in the American colonies, the apprenticeship system that emphasized practical learning. On the other side are the formal U.S. law schools of today.

Reeve retired in 1820 because of poor health, and Litchfield closed in 1833. Competition had gotten intense from the law schools little Litchfield had inspired, such as those at Harvard, Yale, and Columbia.

Its legacy of formalized legal instruction remains, along with an impressive list of more than 1,000 students. The first was Reeve’s brother-in-law, Aaron Burr Jr., who went on to be a Revolutionary War hero, Thomas Jefferson’s vice president, and the man who killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Other graduates were reformist educator Horace Mann, painter George Catlin, and numerous senators, congressmen, governors, and Supreme Court justices.

Reeve left his own legal legacy. He was the author of “The Law of Baron and Femme,” a study of domestic law published in 1816 and reprinted in four editions. Some scholars say it is a proto-feminist attempt to free women’s property from the feudal bounds of marriage.

Reeve’s work also foreshadowed an American abolitionist movement that would not gain national momentum for another 50 years. In 1781, he helped to win freedom for Elizabeth “Bett” Freeman, the first slave to file a “freedom suit” after slavery was theoretically outlawed by the 1780 Massachusetts state constitution. Reeve and lawyer Theodore Sedgwick won the case, Brom & Bett v. Ashley, and two years later Massachusetts declared all slaves within its borders to be free.

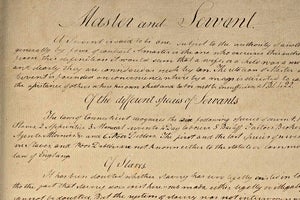

The student notebooks show what Reeve thought was worth teaching: municipal and mercantile law, as well as the laws governing marriage, parenthood, guardians, property, contracts, and the power of sheriffs. Students also listened to lectures on “Servant and Master,” which opened with a discussion of slavery.

Volume 1 of Lonson Nash’s student notebooks, from 1803, offers a contemporaneous look at what Reeve thought about slavery: three pages of notes that contain the lecturer’s opinionated asides. He outlines arguments on behalf of slavery, lines of reasoning that 60 years later were still being employed. But then Reeve’s voice breaks in: “Until there is a Charter given from Heaven to our Sea Captains,” the notebook entry reads, “I shall doubt their wright to separate father & mother brother & sister, bear them into foreign climes, there to linger out a miserable existence in servitude & despair.”

The same passage prefigures slavery’s effect on the nations that hew to it, including the devastation of the Civil War: “It destroys their own ground.”

—Corydon Ireland/Harvard Staff Writer