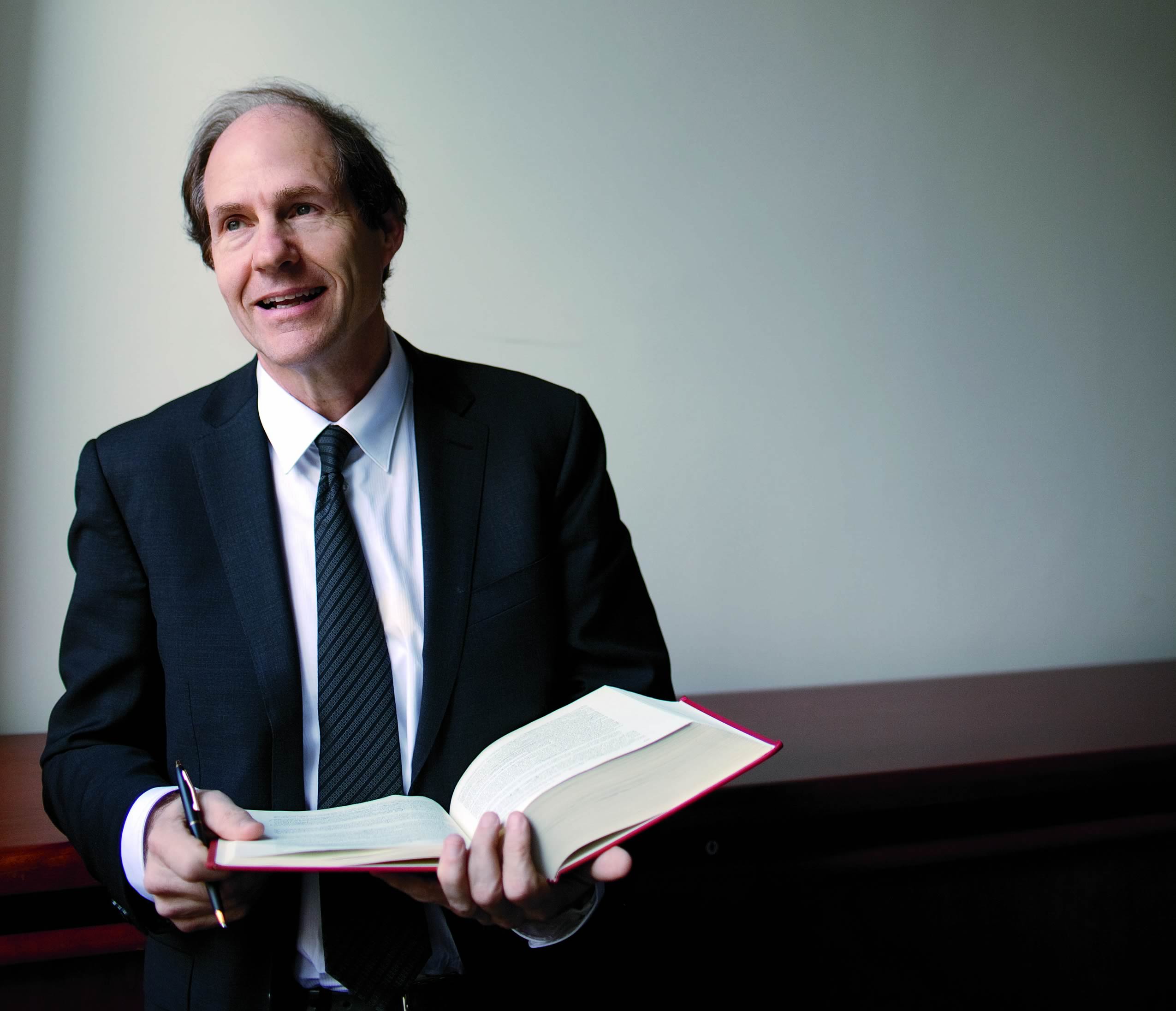

Cass Sunstein and the modern regulatory state

Cass Sunstein ’78, has been regarded as one of the country’s most influential and adventurous legal scholars for a generation. His scholarly articles have been cited more often than those of any of his peers ever since he was a young professor. At 60, now Walmsley University Professor at Harvard, he publishes significant books as often as many productive academics publish scholarly articles—three of them last year. In each, Sunstein comes across as a brainy and cheerful technocrat, practiced at thinking about the consequences of rules, regulations, and policies, with attention to the linkages between particular means and ends. Drawing on insights from cognitive psychology as well as behavioral economics, he is especially focused on mastering how people make significant choices that promote or undercut their own well-being and that of society, so government and other institutions can reinforce the good and correct for the bad in shaping policy.

The first book, Valuing Life: Humanizing the Regulatory State, answers a question about him posed by Eric Posner, a professor of law, a friend of Sunstein’s, and a former colleague at the University of Chicago: “What happens when the world’s leading academic expert on regulation is plunked into the real world of government?”

In “the cockpit of the regulatory state,” as Sunstein describes the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which he led from 2009 to 2012, he oversaw the process of approving regulations for everything from food and financial services to healthcare and national security. As the law requires, he was also responsible for ensuring that a regulation’s benefits generally exceed its costs. By doing so, his office helped the Obama administration achieve net benefits of about $150 billion in its first term—more than double what the Bush and Clinton administrations achieved in theirs. He especially tried to humanize cost-benefit analysis, by focusing on the human consequences of regulations—including what can’t be quantified.

The second book, Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism, is about the type of policy or rule that Sunstein is especially eager to see government and other institutions use regularly: nudging in one direction, with little or no cost to those who decline nudges and go their own way. Little he did in the White House involved nudges, but his job gave him the chance to see many areas of American life where they could make a large difference.

He developed the concept with Richard Thaler, a professor of behavioral science and economics at the University of Chicago. Sunstein defines nudges as “simple, low-cost, freedom-preserving approaches, drawing directly from behavioral economics, that promise to save money, to improve people’s health, and to lengthen their lives”—small pushes in the right direction, like a restaurant disclosing the calorie count of each dish so patrons are more likely to order healthy food, or a company setting up its 401(k) plan so employees are automatically enrolled in the savings program and must choose to opt out.

In recent decades, behavioral economists have shown that, out of impulse, impatience, or ignorance, people often make choices that are not the best or even good for them: we are not the rational self-interest maximizers that conventional economists have long assumed [see “The Marketplace of Perceptions,” March-April 2006]. In response, “choice architecture” (a term Sunstein and Thaler coined) refers to the design of environments in which people make choices—a school cafeteria, say—and to the reality that there’s no such thing as a neutral design. Whether the cafeteria puts apples or Fritos at the front of the line, the placement will affect which snack is more popular. In Sunstein’s view, the cafeteria ought to put apples first. Nobody is forced to take one: the nudge is “freedom-preserving” because a student can choose not to grab an apple.

The third book, Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas, was published to take advantage of his intellectual celebrity. In the run-up to the 2008 presidential election, The New York Times reported that Sunstein was one of the few friends Barack Obama made when both were teaching at the University of Chicago Law School in the 1990s: the friendship elevated Sunstein’s profile when Obama became president. His status as a policy luminary was confirmed by his marriage to Samantha Power, J.D. ’99, who is as close to being a real celebrity (read a profile of Power in the New Yorker) as a policy wonk can be. (“A Problem from Hell,” her Pulitzer Prize-winning 2002 bestseller, is a vivid polemic about U.S. government inaction in the face of genocides [see “An End to Evasion,” September-October 2002]. Obama, still in the Senate, hired her first as a foreign-policy aide and then as an adviser during the 2008 presidential campaign, where she and Sunstein met. She is now the U.S. permanent representative to the United Nations and a cabinet member. Sunstein introduced her at his confirmation hearing before the Senate as “my remarkable wife, brave Samantha Power….”)

The dust jacket of Conspiracy Theories quotes denunciations of Sunstein so extreme it’s hard to imagine what he could have said or done as a government official to trigger such vitriol. Glenn Beck, the conservative commentator, repeatedly called him “the most dangerous man in America”—“Sunstein wants to control you,” he declared, mistaking nudges for edicts of the nanny state: “He’s helping the government control you.”

Before he joined the government, Sunstein explains in this book, his job as an academic was to “say something novel or illuminating,” because today’s “wild academic speculation” could become tomorrow’s solution. Conspiracy Theoriespresents some of those speculations, using the alarums from Glenn Beck and others to draw a wider audience. The title essay, written in the wake of 9/11, is about the proliferation of conspiracy theories then (“49 percent of New York City residents believed that officials of the U.S. government ‘knew in advance that attacks were planned on or around September 11, 2001, and that they consciously failed to act’ ”) and why the theories spread. His purpose is “to shed light on the formation of political beliefs in general and on why some of those beliefs go wrong.”

Believers in conspiracy theories, Sunstein emphasizes, are often ill informed: they believe what they hear—and they hear only from people with extreme views. The scholar Russell Hardin named this problem “a crippled epistemology,” the kind of two-word moniker that Sunstein favors. People who move in and out of such groups make the problem worse. Those who leave tend to be skeptics: when they go, so does their moderating influence. Those who join and stay tend to become fanatics. When a theory attracts fanatics who act on their views, like terrorists, one possible governmental response could be what Sunstein calls “cognitive infiltration”: i.e., challenging the theory’s counterfactual foundations. Some civil libertarians ignored the “cognitive,” read “infiltration” literally, and went crazy denouncing the idea.

The dangerous ideas that most concern him are errors in thinking akin to crippled epistemology that lead to foolish or damaging behavior. They include misfearing, “when people are afraid of trivial risks and neglectful of serious ones,” so public funding is misallocated to combat the former instead of the latter, and the availability heuristic, a mental shortcut in thinking about risk that is influenced by heavily publicized events (floods, forest fires) so people worry about the wrong perils.

These concerns of Sunstein’s are weighty. They also seem narrow, leaving out of the picture the scope of the social purposes that they are designed to serve.

The second essay in Conspiracy Theories, “The Second Bill of Rights,” puts these current preoccupations in crucial perspective. A distillation of a book he published a decade ago subtitled FDR’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More Than Ever, it reveals Sunstein in a very different mood: strongly patriotic and adamantly visionary. He writes about “the only time a State of the Union address was also a fireside chat,” in January 1944, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, only 15 months before his death, spoke to the nation by radio from the White House. To Sunstein, the address “has a strong claim to being the greatest speech of the twentieth century.”

FDR used it to propose a Second Bill of Rights, to redress what he described as the Constitution’s inadequacies. He recommended rights to “a useful and remunerative job”; for “every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies”; to “a decent home”; to “adequate medical care”; to “adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment”; and to “a good education.” They “spell security,” the president said: “For unless there is security here at home, there cannot be lasting peace in the world.”

Roosevelt could make his proposal, Sunstein explains, because in that era “no one really opposes government intervention.” (The italics are his.) The address came only a few years after the end of the Great Depression, when it was all but universally accepted that “markets and wealth depend on government”—to prevent monopolies, promote economic growth, and preserve the system of free enterprise, but also to create “a floor below which human lives are not supposed to fall.”

To Roosevelt, the Second Bill of Rights was like the Declaration of Independence: “a statement of the fundamental aspirations of the United States,” in Sunstein’s words. The president argued not for a change in the Constitution, but for incorporating the rights he championed in “the nation’s deepest commitments.”

Sunstein’s enduring admiration for the proposed Second Bill of Rights helps bring into focus the overarching concern of his career as a legal scholar: to understand and explain how “the modern regulatory state” has changed America’s “constitutional democracy,” and how to reform the workings of government and society to promote “the central goals of the constitutional system—freedom and welfare.”

He has pursued these aims as a preeminent scholar in constitutional law, administrative law, and environmental law, and in related fields. He has also written about animal rights, gay rights, gun rights, the death penalty, feminist theory, labor law, securities regulation, and an almanac of other topics. The span from his microscopic focus on nudges to his panoramic interest in the constitutional system, with nudges carrying out the moral purposes of the Republic, helps explain why his standing in the legal world of ideas is, more or less, Olympian.

Read the full feature, originally published in the January-February 2015 issue of Harvard Magazine.