An innovative education program piloted by the county jail of Flint, Michigan, not only appears to reduce recidivism and misconduct among incarcerated people, but may also bolster participants’ skillsets, improve relationships between the community and law enforcement, and save society money — says a new study co-authored by Crystal S. Yang ’13 of Harvard Law School, Marcella Alsan of Harvard Kennedy School, Peter Hull of Brown University, and Arkey Barnett of the University of Michigan.

The United States has the highest number of incarcerated people in the world, with nearly two million currently behind bars. More than 600,000 people are held in local jails, where most are awaiting sentencing. Recidivism rates are high, with one in four jailed individuals returning to jail within a year of release. Yet opportunities for rehabilitation are few and far between in the U.S., say the researchers.

“Alongside movements to end mass incarceration, as well as reduce existing bias within our system, we believe there needs to be a fundamental shift in how we should treat those who are incarcerated. Nearly all of those incarcerated in jails will eventually return to their communities,” says Yang, the Bennett Boskey Professor of Law at Harvard. Yang’s research focuses on uncovering evidence of the disparities that exist within the criminal justice system, the harms of incarceration to individuals and communities, and programs or policies that can reduce these harms.

“Alongside movements to end mass incarceration, we believe there needs to be a fundamental shift in how we treat those who are incarcerated.”

Crystal S. Yang

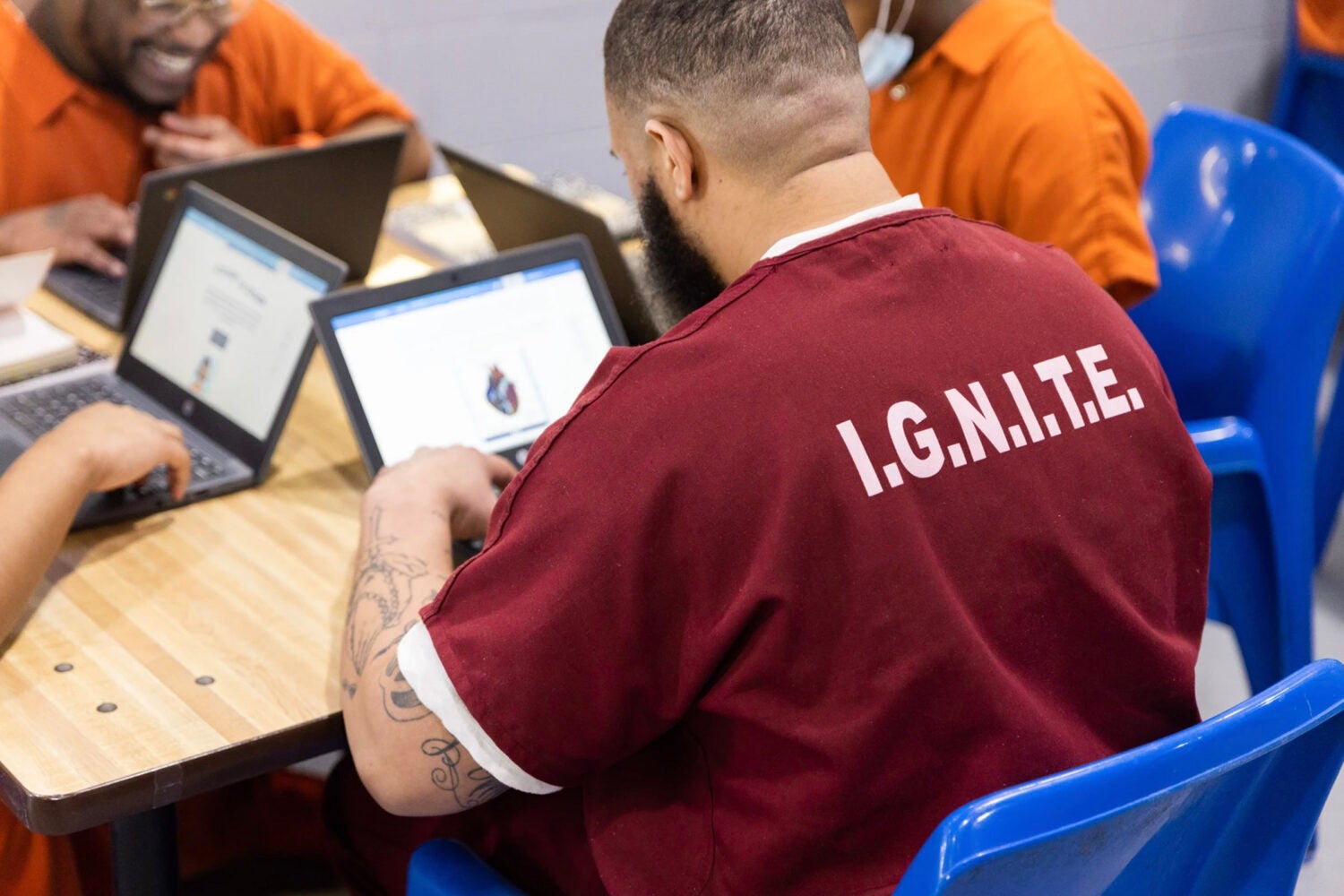

The Michigan initiative is part of a growing number of programs hoping to lead that shift. The initiative, called Inmate Growth Naturally and Intentionally Through Education (IGNITE), was launched by Genesee County Sheriff Christopher R. Swanson in 2020, and offers daily and individually tailored educational programming to nearly everyone in the jail. The program — which operates with negligible added cost — was endorsed by the National Sheriffs’ Association and has started rolling out in other facilities across the United States.

“People can learn to read, take courses for their GED, or do post-graduate work,” says Alsan, the Angelopoulos Professor of Public Policy at Harvard. “In addition, there are courses teaching practical skills in finance, nutrition, and even courses that teach trades such as welding and masonry, facilitated through the use of virtual reality stations. By 2022, the curriculum expanded to include classes like art, creative writing, mental health, mindfulness, and music.”

Alsan first learned about the program three years ago while attending the National Sheriffs Association conference, hoping to recruit jails for another project. Eventually, she and a few of her co-authors visited the Flint, Michigan facility to witness an IGNITE graduation ceremony and learn more about it.

“We have a terrific working relationship with the administration, who trust us and have provided us unprecedented access to their administrative data with the understanding that we would report whatever we found on IGNITE,” says Alsan.

Using novel research methods, which took advantage of random court delays to study the impact of IGNITE, the authors found that one month of program participation decreases recidivism after release by 18 percent over three months and 23 percent over a year. Participants gained a full grade level of improvement in reading and math scores, which likely contributed to the recidivism reductions. These additional skills can provide new possibilities to participants, says Peter Hull, a Professor of Economics at Brown.

“Some incarcerated individuals seem able to break through the cycle of recidivism, which affords them more opportunity to further the education they started in IGNITE and secure employment,” he adds.

The program seems to not only reduce recidivism after release, but also dramatically cuts misconduct within the jail. The researchers found that one additional month in jail reduced major misconduct incidents each week by 49 percent, including reductions in violence or threats of bodily harm.

The researchers say IGNITE is unique because it requires very few additional resources, and because the program is led by law enforcement officers in existing spaces within the jail. According to Yang, these positive interactions between jail officials and incarcerated people may also have other benefits.

“We conducted a community survey in Flint County and found some suggestive evidence that those exposed to the IGNITE program were more likely to be engaged in ‘positive activities’ such as caregiving in their own families or working in the formal labor market,” she says. “More broadly, we find clear evidence that community members have more positive views of law enforcement if they or their family members had been exposed to the IGNITE. This is a true spillover effect, since the custody staff at Genesee County Jail are different from the arresting police in the community. These findings indicate that IGNITE may have improved perceptions of procedural justice and trust in police.”

All these results — the reduced recidivism and misconduct, additional life skills for incarcerated people, and improved views of law enforcement — add up to savings for society. The researchers estimate that one month of program exposure saves around $5,600 per person per year.

Alsan says she is excited to see how the program fares as it expands beyond Flint into jails across the U.S.

“In addition to an educational program, IGNITE represents a substantial cultural shift, with incarcerated individuals more aware of opportunities and deputies more acclimated to providing education,” she says. “Currently, the NSA is trying to scale the program to other jails across the country, and we hope to continue our work to study whether these efforts are successful.”

If they are, it could be a giant leap forward for those who envision a different kind of criminal justice system, says Yang.

“We have much to learn from countries like Norway, where the correctional system is guided by the simple question: What kind of neighbors do you want? Not offering programming such as IGNITE to all incarcerated individuals seems like a hugely significant missed opportunity for our society.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.