Though law and fashion may not initially seem like overlapping domains, given the central nature of each of these fields it is no surprise that they do have an impact on one another. Over the years, fashion has been important to decisions about how jurists visually demonstrate their expertise and law has served to circumscribe how fashion is created, distributed, and consumed.

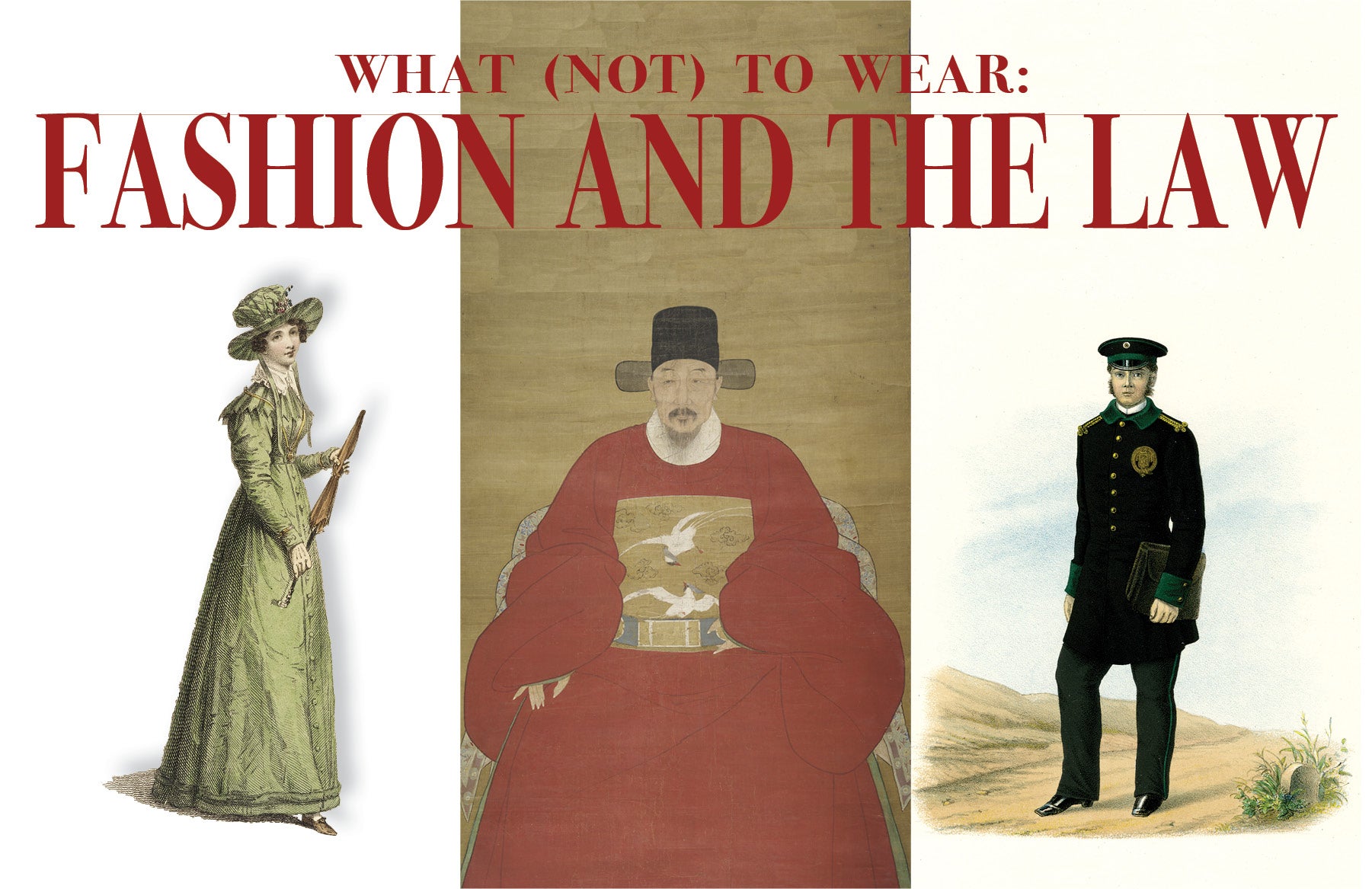

The latest exhibit from the Harvard Law School Library, “What Not to Wear: Fashion and the Law,” looks at some of these intersections of fashion and the law, from historic laws setting strict class distinctions for fashion, to modern intellectual property law’s approach to protecting those who design and create fashion.

Curated by Mindy Kent, Meg Kribble, and Carli Spina, “What Not to Wear” is on view in the HLS Library’s Caspersen Room daily from 9 am–5 pm through August 12, 2016.

You can also see an online addenda to the exhibit at http://exhibits.law.harvard.edu/current-exhibit (selected entries below).

You can find information about HLS Library online at https://hls.harvard.edu/library, or visit their blog, Et Seq. to learn more.

Sumptuous Origins

Over the millennia, sumptuary laws–those governing the consumption and display of luxury goods–have been used to reinforce social hierarchy, protect public morals, control trade, and identify those viewed as “other”—namely non-Christians and prostitutes. Sumptuary laws over the centuries, ranging from the humorous to the sinister are the focus of this section of the exhibit.

Although sumptuary laws may no longer restrict who can wear gold or lace, the law and regulations of many societies require specific uniforms and insignia to indicate position and authority. Other communities adopt ceremonial regalia to emphasize a connection with history or a sense of occasion. Uniforms demonstrate power and immediately identify role and rank, whether military or civil. Examples in this exhibit show how different governments and organizations choose to distinguish and represent their authority.

Rules and Regulations

Over the course of history, law has been called upon to regulate fashion in a number of ways. Often this regulation pertains to issues of public health. Though we may not frequently think about it, clothing does have the potential to be toxic, a fact that was driven home in the late 1800s by the health problems that arose from the use of arsenic in certain dyes. This may have been an early and dramatic example of laws being used to protect people from the chemicals in their clothing, but it is by no means that only example. In this way, fashion can intersect with even health and safety legislation.

As a creative field, those working in the fashion world also look to the law to protect their work and livelihood. Intellectual property law has long struggled with how fashion and its related innovations fit into the realms of patent, trademark, and copyright law. Though many of these questions have not been definitively answered, this is a fascinating area of ongoing legal debate and another way in which the law intersects with fashion. Read More

“What (not) to Wear: Fashion and the Law” is on display in the Harvard Law School Library’s Caspersen Room daily from 9 am — 5 pm through Friday (August 12). For more information about this and other Law Library exhibits, its digital collections, its historical and special collections and much more, visit http://hls.harvard.edu/library/