According to President Ronald Reagan, “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’” The attorneys general of Missouri and Louisiana tend to agree, at least when it comes to federal government involvement in social media platforms’ content moderation policies. But what would the U.S. Constitution’s drafters, including Benjamin Franklin, think?

On March 18, the justices will hear oral arguments in a case, Murthy v. Missouri, in which the two states and several individuals claim that federal officials violated the First Amendment in their efforts to “help” social media companies combat mis- and disinformation about COVID-19 and other matters. In what they label a “sprawling ‘Censorship Enterprise,’” the parties that filed the suit contend that the Biden administration has effectively coerced the platforms into muzzling the voices of Americans, particularly conservatives, who question public health pronouncements about the pandemic or the efficacy of vaccines.

This is one of several landmark social media cases the Court is hearing this term, including Lindke v. Freed and O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier, in which they will decide if and when government officials may block private citizens from commenting on their personal social media accounts. The justices’ rulings in these and other cases could transform the way government may regulate the conduct of social media behemoths.

Former national security official and current Harvard Law lecturer, Timothy Edgar ’97, believes that both the states and the federal government have valid arguments, and argues that the justices should channel the spirit of that famous 18th century publisher and postmaster, Benjamin Franklin, who was a proponent of both neutrality and rational discourse. Harvard Law Today recently spoke to Edgar about the case, the arguments on both sides, the legal precedents, and what one of America’s most famous founders might do.

Harvard Law Today: What is this case about?

Timothy Edgar: This case is about whether the government can be involved in content moderation decisions. And it’s a very important case for social media because social media relies on content moderation. But when the government gets involved, there’s very serious issues about censorship and freedom of speech.

HLT: And what are the states and individuals that sued the federal government arguing?

Edgar: Missouri among other states and individuals are arguing that the Biden administration’s involvement in trying to suppress COVID-19 misinformation, especially about vaccines, crossed the line from being public health education to being censorship, by proxy. They argue that the administration was making very aggressive, specific suggestions to those social media companies, either to remove or to downgrade certain kinds of posts, and that by doing that, they transformed the private decisions that those companies made — principally Facebook and Twitter, now X — into public decisions, and that would amount to censorship.

HLT: How does the Biden administration respond?

Edgar: The federal government says this was a voluntary, cooperative effort between social media and the government to combat misinformation and improve public health. They also argue that the government has long engaged in public health education and that even if the government expresses its views bluntly, it has a responsibility to express those views. The First Amendment and concerns about censorship, they say, don’t prevent the government from expressing an opinion about what information is or isn’t truthful when it comes to public health, or to tell a social media platform, “We think that under your policies, you should be taking action to combat this misinformation.”

HLT: Who has the better argument, in your view?

Edgar: My opinion is that they’re both right and that we need to get some clarity from the courts about where that line is between engagement and public health or other issues as well, such as terrorism, online radicalization, efforts to remove child sexual abuse material, and a whole range of other public policy issues that involve content moderation on social media. We need guidance from the courts about what communications are okay, and what communications cross the line.

HLT: Is there existing tradition or jurisprudence on this question that the justices can turn to? I realize that Chief Justice John Marshall was not dealing with questions about social media content moderation in the first decades of the 19th century.

Edgar: Since you mentioned Marshall, I can’t resist telling you about my class, “Legal Problems in Cybersecurity” and our recent discussion on the topic of disinformation, which began with a quote from Benjamin Franklin. In his early days, Franklin was a printer in Philadelphia and a postmaster. When he was criticized by a number of the citizens of Philadelphia for publishing a controversial essay, Franklin wrote a famous response called “An Apology for Printers,” which is a defense of the idea that printers should be neutral. Here’s the quote: “Printers are educated in the Belief, that when Men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that when Truth and Error have fair Play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter: Hence they chearfully serve all contending Writers that pay them well, without regarding on which side they are of the Question in Dispute.”

Franklin was defending the idea that there’s a role for service providers — publishers, printers, platforms — to share information and arguing that, if we say that they must agree with everything that’s on their service, then we cut off debate. It is an argument grounded in an enlightenment faith in the idea of rational discourse. Of course, it doesn’t answer the question of whether we should print literally everything — which Franklin did not believe — or when and how platforms should moderate content. But it embodies a certain faith in the marketplace of ideas.

Franklin is making two arguments in his essay. One is the enlightenment idea of rational debate: that the truth will win out. But it also has this very pragmatic point, which is that neutrality is good for business. Printers were natural monopolies in a way that social media platforms can be as well. Printers had expensive equipment, and the market couldn’t support many printers of differing beliefs, even in a relatively large city or town like Philadelphia. So, to serve the public, you need a platform — a printing shop and now a digital platform — that maintains some level of neutrality in order to have a democratic system of government.

“Franklin was defending the idea that there’s a role for service providers — publishers, printers, platforms — to share information and arguing that, if we say that they must agree with everything that’s on their service, then we cut off debate.”

HLT: How about legal precedents?

Edgar: There are precedents from the pre-digital era. The most important is a case called Bantam Books v. Sullivan, from 1963, which involved government communications to book publishers that were selling what state officials considered “objectionable” books because they were inappropriate for minors. The state urged “cooperation” and reminded booksellers of the potential for prosecution if the books were later found to be obscene. The publishers sued and won on the argument that those communications were a form of censorship, not voluntary cooperation. They crossed a line. So, we know that there is a line. When the government communicates with distributors of information, in that case, book publishers, if they do it in a way that makes those businesses feel like they have no choice but to comply, then those actions will be seen as government actions. And they will be seen as a form of censorship that is prohibited by the First Amendment unless there’s some legal basis for censorship, in other words, unless the content is illegal. So, that’s a good precedent to apply here. But it doesn’t answer a lot of questions about where that line actually is. Attempts by lower courts to apply the Bantam Books standard in the digital age have been a bit messy.

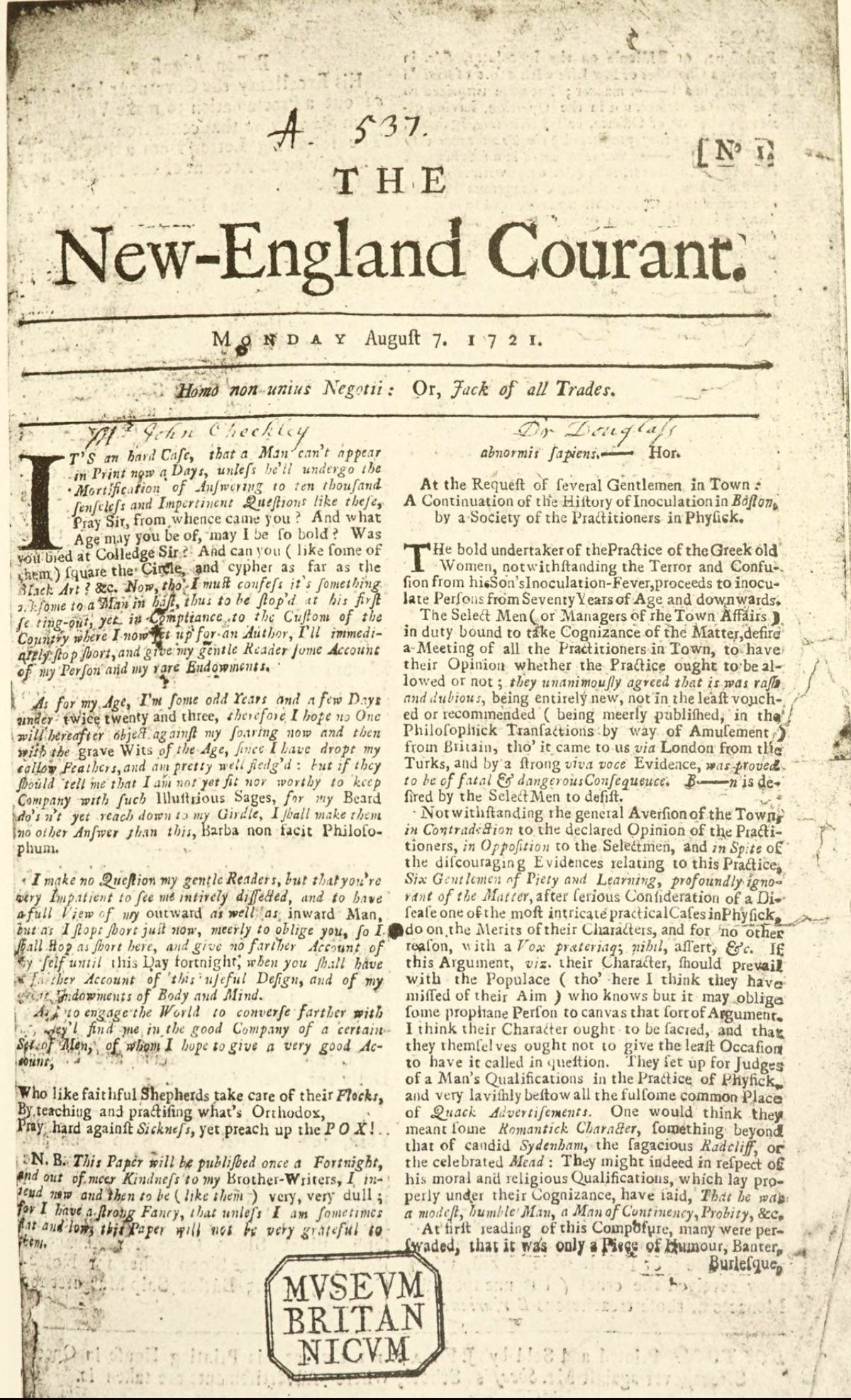

HLT: The essay you cited from Ben Franklin seems particularly apt because, if I remember the history correctly, it was a very young Franklin who helped his older brother publish arguments against the idea of smallpox vaccinations, which Cotton Mather was urging but many in the Boston establishment opposed.

Edgar: You got it exactly right. It was very early in Franklin’s career. Franklin was born in Boston and very famously he skipped out on his apprenticeship before it was done and hightailed it to Philadelphia, where he made his way. During his time in Boston, he apprenticed at his brother’s newspaper, which had taken a strong anti-inoculation stance. We know now that it was bad for public health. And Franklin, as a man of science, became a huge champion of inoculation later in life. We have writings where he deeply regretted being involved in the campaign against inoculation in Boston. That doesn’t necessarily mean that he would want the government to suppress anti-inoculation printers, but it shows you again that there’s a role for content moderation.

HLT: So, what can we learn today from Ben Franklin about where the line might be?

Edgar: You can look at this example from Franklin’s life and see some of both sides of what the justices will be deciding in this case. The platform should be neutral. In general, they should aspire to further public debate and that, even when they think something they allow to remain posted to the platform is wrong, they should have some faith in rational discourse. But there is a line, and the platforms or the printers can draw that line where they choose. The problem is when the government gets involved in telling those platforms where and how to draw that line. And even there, it’s more complicated because the government has the obligation to inform the public on matters where they’re the most authoritative source. And they often are the main source of reliable information, including on matters of public health.

The government has a responsibility to inform the public and to engage with digital platforms. They may even criticize digital platforms if they feel that their moderation decisions are being driven by private profits at the expense of the public interest. In such cases, the government can call out platforms and say, “We think you’re permitting this kind of information in order to generate private profit and not because you’re trying to encourage a well-informed discussion about public health.” The government can make rational arguments. What it cannot do is to invoke its power — even implicitly — in a way that makes platforms feel they have no good option but to do what the government says.

“[T]here’s a difference between X and Facebook and the New York Times. Platforms make content moderation decisions. The New York Times makes editorial decisions. Both are protected by the First Amendment, but they are different decisions, and different considerations apply when deciding when government pressure crosses the line.”

HLT: Right, so how does a court decide what crosses that line? Is there an established test?

Edgar: The amicus brief filed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, EFF, and the Center for Democracy and Technology, CDT, had a good recommendation: In deciding whether government has crossed the line, courts should look to the standard in Bantam Books. Lower courts have looked at several factors. One of those is transparency; are the government’s views freely accessible to the public? Or are they being privately communicated to the platforms? If the government’s views are transparent — allowing those who disagree to push back — its actions are less likely to seem coercive. Second, what kind of language did the government use? Did they say, “Hey, we want to point out there are some posts about vaccines that are misinformation, and we think they don’t comply with your community guidelines.” Or, did they say, “Take this post by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. down by tomorrow. If you don’t do it, we’re going to call you.” That is more directive language that might cross the line. Third, is the government using persuasive arguments? “Here are the reasons why this post violates your guidelines.” Or did they refer to their statutory authority, directly or indirectly, as the head of the CDC, or another public health agency? “The law gives me the responsibility to ensure public health, including through certain enforcement powers” might sound like “I’m ordering you to do this.” Fourth, are they really getting into the nitty gritty of exactly which posts they say are objectionable versus those that aren’t? Or are they giving more general guidance about what the platforms should know about the issue as they consider content moderation decisions? Finally, did the platform ask for this? Did they say, “Hey, we’d like your expertise in as we identify things that violate our guidelines? Let’s have some periodic meetings and discussions and have a channel.” Or did the government reach out and say, “We want to clean up this platform.” None of those are dispositive — they provide a multifactor balancing test — which can, of course, be fuzzy.

HLT: Is there a way for the Court to make that multifactor balancing test less fuzzy?

Edgar: In their amicus brief, EFF and CDT suggest that the Court should put the burden on the government to show that they didn’t cross the line. So, the government has to make sure that its communications with platforms are staying on the side of information, recommendation, education, and even criticism, but don’t cross into coercion, pressure, implied threats, or invoking authority. And if you put that burden on the government, I think that gives more teeth to this multifactor balancing test and maybe makes it a little clearer.

In the Murthy v. Missouri case, the states describe a host of contacts between federal officials and the platforms, many of which probably fall on one side of the line and some of which on the other. And I think part of the problem is that the lower courts took a very blunderbuss approach, saying this is all unconstitutional censorship, which I think is wrong. The government has an important role and responsibility here to be engaging with private platforms, and not just on public health, but on issues of terrorism, and extremism and violence, on issues of taking down illegal content like child sexual abuse material. When there are foreign, state sponsored disinformation campaigns, the government is uniquely positioned to let the platforms know about them. So, they need to be involved with Facebook, X, Google, YouTube, all the big social media companies. It must be voluntary, but it makes a good deal of sense for the public to expect those companies to have good and productive, voluntary cooperative relationships with relevant government agencies that have expertise in these areas. But it must be very carefully done. And it must be transparent. And it must be done in a way that doesn’t cross that that important line.

HLT: Does the type of content matter? Does the government have more or less leeway when it is an urgent matter of public health or national security compared to when the risks to health, safety, or even democracy are less obvious? I’m thinking about social media posts related to Hunter Biden’s laptop, for example.

Edgar: Obviously, there are hot button political issues where any government involvement will raise real questions in the minds of any average American about whether this is genuinely fulfilling some important national security or other interest or whether this is protecting the president’s son, in the case you mentioned. That said, there may be legitimate national security interests involved even — or perhaps especially — in highly fraught political issues. The Russian government is going for the jugular. They’re going after the issues that affect the political debate in their efforts to influence political action with misinformation or disinformation. So, it’s heavily fact dependent on what happened in the case of, say, Hunter Biden’s laptop. If there is information about Russian involvement in promoting a story, I think that’s relevant for social media companies to know about. But you don’t want these kinds of initiatives used for political purposes, where politically damaging information or stories are flagged by the government on some pretextual ground. If it were Hunter Smith’s laptop, what approach would the government take? So again, it’s a context-based question about what happened in that case and what the government’s interest is. But I don’t think you can shy away from having this kind of involvement by the government involving foreign disinformation threats just because it’s politically fraught, because then you’d be tying your hands behind your back. Obviously, foreign based political disinformation is going to be about politically fraught issues, or else it wouldn’t be very effective.

HLT: How about different types of platforms? Government officials and PR people jawbone journalists all the time, trying to influence what they write and publish. Newspaper op-ed pages regularly decide which opinion pieces by outside actors to print, and which not to. Is there a difference between Facebook and X and the New York Times op-ed page in the way government officials can interact with them?

Edgar: Yes, there’s a difference between X and Facebook and the New York Times. Platforms make content moderation decisions. The New York Times makes editorial decisions. Both are protected by the First Amendment, but they are different decisions, and different considerations apply when deciding when government pressure crosses the line. And this gets back to our discussion of Benjamin Franklin. In the social media space, content moderation may deprive a speaker of the practical ability to have access to digital public square. That’s different than, say, the White House press secretary yelling at the editor of the New York Times because she doesn’t like the tenor of the paper’s editorials, or she thinks that they shouldn’t have run a particular story. Of course, if such contacts get into coercion and threat, then they do violate the First Amendment. But just in terms of the overall context, people expect government press officers to be yelling about that kind of stuff. It’s part of the editorial process. Whereas if you’re talking about the Department of Homeland Security or the intelligence community or the CDC or the Surgeon General making official statements about information that shouldn’t be out there because it’s harmful to the public, that is a different kind of pressure and could well cross the line.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.