Harvard Law School was founded with a bequest from Isaac Royall, a brutal slave owner. Two centuries later, the first black President of the U.S. and first black First Lady are HLS alumni.

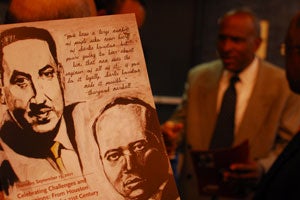

Examining that arc was the subject of “Celebrating Challenges and Champions: From Houston to Marshall to the 21stCentury,” an event sponsored by the HLS Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice and Amherst College’s Charles Hamilton Houston Forum on Law and Social Science. Moderated by Charles Ogletree ’78, HLS Jesse Climenko Professor of Law and Director of the Institute, the event kicked off the 3rd Celebration of Black Alumni, which brought more than 700 alumni from around the country to campus over the weekend of September 16-18. Speakers included the son of Charles Hamilton Houston ’23, considered the architect of the legal strategy behind the modern civil rights movement, as well as Dean Martha Minow and other former clerks of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

The history of HLS includes both disturbing and inspiring aspects, said Daniel Coquillette ’71, J. Donald Monan Society of Jesus University Professor at Boston College and the HLS Charles Warren Visiting Professor of American Legal History, who is writing a two-volume history of the school and spoke on the history of African Americans at HLS.

“The founder of this school burned 70 slaves at the stake,” said Coquillette, noting that the HLS shield depicts three wheat sheaves that were part of the Royall family’s coat of arms. Yet when Coquillette visited Antigua recently as part of his research, he found the locals proud of their connection to HLS. “It’s a matter of great pride to the people of Antigua that the labor of enslaved Antiguans helped found the school where Barack Obama graduated,” a local historian told him.

Except for West Point, no single national school contributed as many leaders to the Confederacy, Coquillette said, including 11 generals and 18 members of Jefferson Davis’ government. Because of a major recruiting effort to establish HLS as a national school by then-Professor Joseph Story, who simultaneously served on the U.S. Supreme Court, 30 percent of students in the 1850s came from the Deep South. Charles Sumner 1834, a lecturer at HLS, found his promising career at HLS cut short after he became a passionate abolitionist. George Lewis Ruffin 1869 and Archibald H. Grimke 1874, the first two blacks to graduate from HLS, entered a school that was still a “stronghold of anti-black feeling,” Coquillette said.

Ruffin served as a Massachusetts court judge until his death 1886, and Grimke, an escaped slave from South Carolina, became national vice president of the NAACP. Both men, whom Coquillette described as “deeply courageous,” are completely ignored in Charles Warren’s 1907 treatise, “History of the Harvard Law School and of Early Legal Conditions in America.” Arthur Sutherland’s “The Law at Harvard: A History of Ideas and Men,” published in 1967, mentions neither man nor Charles Hamilton Houston.

“We’re not asking for a special place in history, we’re just asking to be remembered,” said Ogletree.

The event, which began and ended with a slide presentation highlighting the civil rights movement and featuring a live vocal performance by Lawrence Watson, an associate professor at Berklee College of Music and the Houston Institute’s Artist in Residence, examined the civil rights movement through the work of many of HLS’ most influential alumni, including Houston, Marshall, and others.

Nancy Gertner, who has joined the HLS faculty as a professor of practice after retiring last month from 17 years on the federal bench in Boston, said the overt racism in the society of 50 years ago has been replaced by subtle and implicit bias. Civil rights laws haven’t been overturned, she said, but their spirit has been undermined by judges who believe the battle is over and are hostile to claims of discrimination. The challenge for both the Houston Institute and HLS “is to begin to surface ways in which discrimination has continued even if unrecognizable to many of the judges on the bench,” Gertner said.

John Payton, president and director-counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, said that it’s a myth that courts were ever widely receptive to the civil rights movement and he urged maintaining perspective on the current courts. When Charles Hamilton Houston appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1938 to argue the landmark case Gaines v. Missouri, first in a line of cases culminating in Brown v. Board of Education, Associate Justice James McReynolds “turned his chair around rather than face a black man,” Payton said, adding, “There are hostile courts, and then there are hostile courts.”

The concept of an anti-discrimination principle, so widely embraced today, didn’t exist even as an aspiration until Charles Hamilton Houston suggested it as essential to the civil rights movement, Payton said. “The most astonishing thing about him was his ability to see past his time,” Payton said. To the audience of lawyers, Payton said, “We are a very empowered profession … we can challenge injustice. That’s what Charles Hamilton Houston saw.”

Three graduates of HLS shared anecdotes about their famous parents, including the dangers they faced during the civil rights movement: Joel Motley III ’78, son of Constance Baker Motley, a legendary civil rights lawyer who won 9 of her 10 U.S. Supreme Court cases and wrote the original complaint in Brown; Charles Hamilton Houston Jr., an assistant professor at Morgan State University; and Thurgood Marshall Jr., a partner at Bingham McCutchen. Justice Marshall was remembered as a brilliant attorney, passionate advocate for social justice, and witty practical jokester by his former clerks, who, in addition to Minow included HLS Professors Scott Brewer, Randall Kennedy, Vicki Jackson, and Mark Tushnet. They noted that Marshall was a “stickler for procedure,” as Tushnet put it, and suggested this was due in part to his realization that, as a black lawyer in the 1940s and ’50s, he must strictly adhere to court rules to avoid his cases being tossed on technicalities. Minow called Marshall’s work “a jurisprudence of speaking truth to power,” and said his devotion to procedure inspired her to make civil procedure her area of professional study.

While widely regarded as a superb advocate even among his detractors, in some circles Marshall is seen as an indifferent justice, a notion that Randall Kennedy dismantled. “On things that mattered the most, he voted the right way—and yes, he was an activist judge,” said Kennedy, noting Marshall’s dedication to issues of life and death, equality, and social justice. ”And for these reasons, he was a great judge.”