As a young federal public defender in Baltimore, Alexandra Natapoff represented numerous cooperators. But it was teaching a civil rights class in a local community center that showed her the deeper impact of the government’s use of informants.

“I got a question,” said a young boy in her class, in a scene she recounts in her recently reissued book. “Police let dealers stay on the corner because they’re snitchin’. Is that legal? I mean, can the police do that?” Natapoff explained that yes, police do have discretion to make deals with active drug dealers. “That ain’t right,” he scowled. “They ain’t doing their jobs!” said another student. “So, all you gotta do is snitch,” a third said, “and you can keep on dealing.”

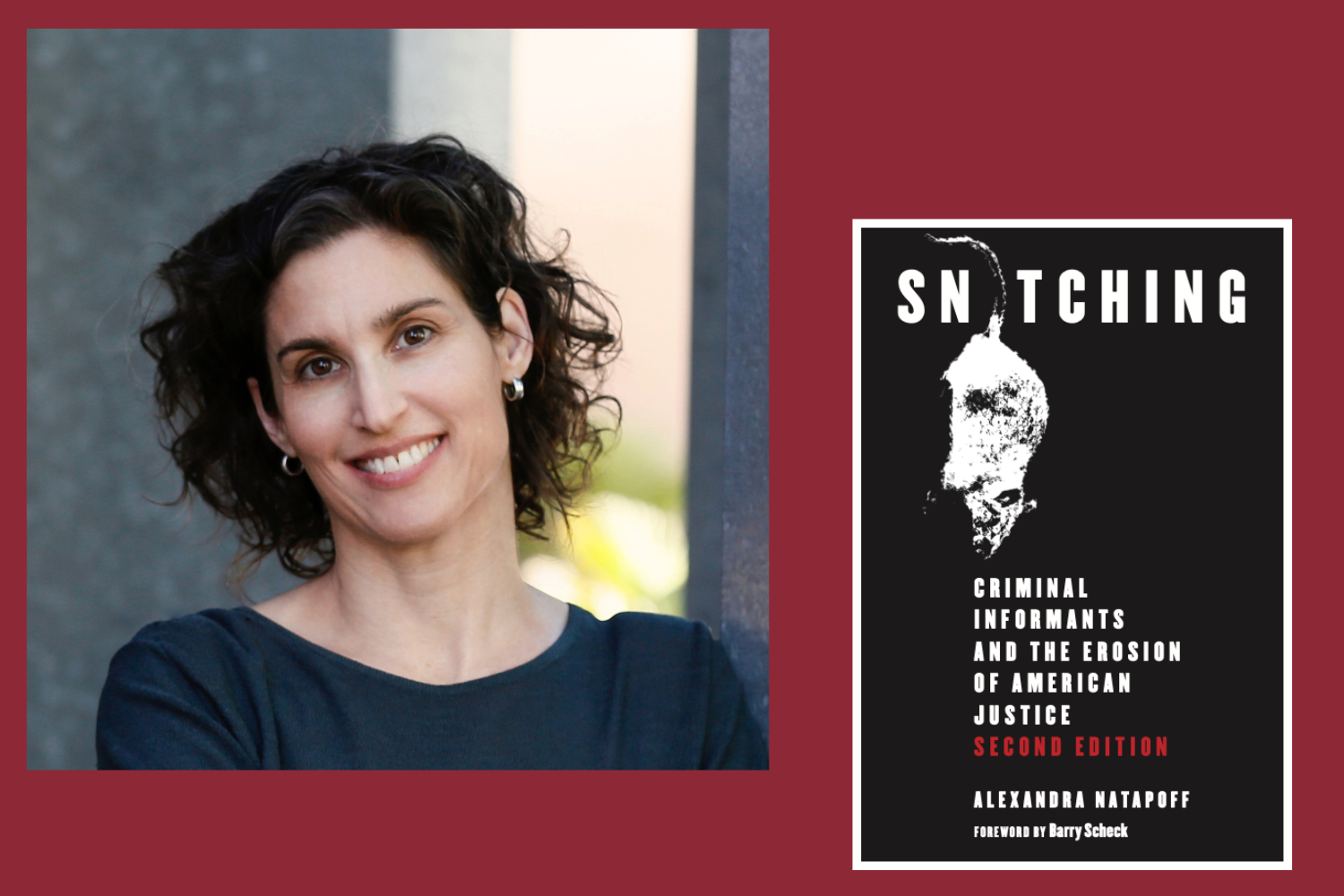

At that moment, Natapoff realized that children in heavily policed communities across America “understood that the justice system was being sold out in this very profound way on their very own streets.” It was also the genesis for her book, first published in 2009, “Snitching: Criminal Informants and the Erosion of American Justice.”

Now the Lee S. Kreindler Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, Natapoff has completely revised and updated her book; the second edition accounts for and responds to the many developments in American informant law and culture over the past decade, some of which she has been involved in generating herself. In a recent interview with Harvard Law Today, Natapoff explains how and why she believes “we have conferred on the government enormous unregulated power to leverage its extraordinary coercive criminal authority against almost anyone in exchange for almost anything.”

Why snitching?

HLT: How do people become criminal informants? And how and why do prosecutors use them?

Alexandra Natapoff: You can’t understand criminal informants in the American system if you don’t understand plea bargaining. Ninety-five percent of all criminal convictions in this country are the result of a plea deal, not of a trial. We almost never litigate guilt. Instead, in effect, we’ve created an enormous space for negotiation. That plea market is highly deregulated relative to the trial space. And the informant world is worse: it’s the under-the-table, black-market version of plea bargaining, where anything can be negotiated with anyone in exchange for almost anything. It is an all-bets-are-off space where the most serious crimes can be worked off. And conversely, where the most vulnerable people can be pressured into risking their lives.

Anyone can become an informant — the state can cut a deal with anyone. Which means informants can be the most serious criminal actors or the most vulnerable people. And we almost never constrain the state in what it can negotiate for. So, perhaps most famously, the state can pressure informants to risk their own lives in exchange for a deal, but it can also pressure informants to have sex with people who they don’t want to have sex with. It can pressure informants into exposing themselves to drugs and drug use, even when the informants themselves are at high risk because they have substance use disorders. It can even pressure children into doing such things. The range of leverage and coercion available to the state is almost unlimited.

At the same time, the state can dangle almost anything it wants. The most famous thing it can dangle is leniency. ‘We won’t arrest you. We won’t charge you. We will let you continue to commit criminal activities, even when it involves the victimization of others.’ It can also offer money, immigration benefits, or better conditions of confinement. It can also offer leniency for third parties. We call it a ‘wired plea’: you cooperate so that your mother, father, child, or partner can get a benefit. Basically anything you can think of that can be used to pressure or reward or benefit or induce is pretty much on the table.

HLT: What’s the benefit to the public?

Natapoff: That’s the million-dollar question: What’s the overall social good of this informant market? And the answer is, we don’t know. Because the government isn’t obligated to keep track either of the costs or of the benefits, and it is not obligated to tell us what those costs and benefits are. So, we are disabled, in a democratic sense, from having the public discourse and conversation around that all-important question: under what circumstances might it be worth cutting a deal with an informant who has harmed others or committed serious crimes in exchange for the state’s ability to prosecute someone else? And conversely, when is it too costly to let the government use this extraordinary coercive power against so many people under so many risky situations?

The conventional answer that law enforcement gives is that it needs to be able to cut a deal with the little fish to get the big fish. In other words, without the ability to flip low-level offenders, we can’t get to John Gotti, or Kenneth Lay, or Congressperson Fill-in-the-blank.

Sometimes we do see big fish stories. The FBI tells us that it could not have dismantled organized crime without relying on violent mafia informants. It’s worth remembering that those informants themselves killed dozens of people and continued to kill people while they were working for the FBI. Congress even issued a scathing report called “Everything Secret Degenerates,” about the FBI’s use of murderers as informants in connection with this multi-decade effort to take down organized crime. So, even the most famous, quote unquote, ‘success story’ was rife with very disturbing decisions by government officials.

But that story — that we need the little fish to get the big fish — is not actually how we run the informant market. It is much sloppier and less principled. Big fish have more information than little fish. So, it turns out, they’re more valuable to law enforcement than little fish. And time after time, we see the government cutting a deal with a relatively high-level operative, who then turns in their subordinates — the couriers, the runners, the people with substance use disorders, the low-level operatives. So, in effect, we often get it backwards. We’re cutting deals with the most culpable people at the expense of people who are not as culpable. And again, we don’t require the government to document either the costs or the benefits of these deals, so we don’t know how often this happens.

Trust between informants and law enforcement

HLT: Given the coercive tools in the hands of police and prosecutors, how do they know the informants aren’t lying?

Natapoff: Police and prosecutors, when they speak frankly about the use of informants, tell us that they rarely have any way of knowing whether their informants are telling the truth. And the more reliant on informants they are, the less able they are to figure out whether their informants are reliable or not. One prosecutor calls it ‘falling in love with your rat.’ The way they describe it, you become dependent on an informant who is helping you make cases, and you adopt their version of events and become dependent on their evidence, because it is advancing your case and your career. This is, of course, an invitation to informants to invent or fabricate or manipulate. We know that informants, for example, target their rivals. They use the informational power that the state confers on them in ways that are helpful to themselves. Notice that this is a profound distortion of the penal power. We depend on government officials, police, and prosecutors to wield their selection power in pursuit of the public safety and the public good. But instead, we have created an arrangement in which that power is essentially outsourced to individual suspects to deploy in whatever way they can get away with.

HLT: What are the potential downsides for defendants who are pressured into becoming informants?

Natapoff: I think it’s important to recognize what a vast range of people get swept into the system and can become informants. Famous stories about informants that make it into Hollywood movies tend to be the high-level informants who are getting leniency while also running rampant. But then there are also informants for whom it is a terrible idea to become an informant because they’re getting little to no benefit. They acquiesce out of fear of coercion and lack of choice. They don’t know what their options are. But we permit the state to leverage that fear and uncertainty to get people to cooperate and to undergo very risky operations in cases where it is clearly not in the informant’s interest.

Let me share one example from the book. A young woman named Rachel Hoffman, who was a new college graduate, was caught with some marijuana and a few pills, and Florida police pressured her into becoming an informant by threatening her with jail. They sent her on a sting to sell drugs and a gun to two targets they were interested in. And during the sting, they lost track of her. The targets found the wire in Rachel’s purse, and they killed her. There is now a law in Florida called “Rachel’s Law,” which is named after her. Rachel Hoffman never should have become an informant. The benefits to her were too small and the risks were too high. And we see that over and over again, that vulnerable people enter into these deals because of fear and lack of information.

Informing inequities

HLT: You write that this system disproportionately impacts communities of color, underrepresented minorities, and heavily policed communities.

Natapoff: There’s a chapter in the book about the community cost of using informants in which I zero in on a phenomenon that I think has been almost entirely overlooked in our penal system. Because we over-police Black communities and low-income communities for drugs, we also overuse informants in those communities. We don’t have direct data because we don’t require police to tell us how many snitches they flip in any particular community. But we do know from police and prosecutors that the war on drugs involves the heavy use of informants. The result is that the people who live in those neighborhoods are overexposed to the crimes and the violence committed by informants.

And maybe just as insidiously, they’re exposed to the knowledge that justice is for sale. That this is not a principled endeavor; it’s a deal. We over-punish individuals in these communities in extraordinary and harmful ways when they commit a crime, and at the very same time we turn right around and say that their suffering is negotiable: “If you can be helpful, then everything is on the table.” That is a terrible, cynical, hypocritical message to send to communities that have been devastated by heavy law enforcement.

This is one of the stunning things I learned when I was a public defender in Baltimore, before I became a law professor. My neighbors, my friends, the young people who I worked with in the neighborhood knew that they were living in this unprincipled world in which police were cutting deals with drug dealers on their own street corners, even as they and their friends and their family members were being rounded up every Friday night and being arrested and taken to jail for the allegation of minor criminal activity. Of all the things I’ve learned about snitching over the years, I think that is the one that has been the most philosophically profound, that we have announced to the communities we punish the most that crime and punishment are morally negotiable.

HLT: How does this system work for white-collar crime?

Natapoff: There’s a whole world of informant use in white-collar crime, in political corruption, in corporate malfeasance. It works quite differently — that’s why the book chapter is called “How the Other Half Lives.” The deal is the same. The commodification of guilt is the same. But these are well-resourced defendants. They typically have some of the best attorneys. And the state handles them much more carefully with much more respect. These examples show that state actors know how to handle informant deals in a transparent and lawful way. They just appear to do it only when they are forced by the resources of the putative defendant to do so.

But snitching is still snitching. We see familiar concerns about crime on Wall Street that, because we have sent this message that guilt is negotiable, corporate wrongdoers understand that they can work off their liability. The prevalence of cooperation tells the hedge fund inside trader that they will not go to jail. If they get caught, they will have the opportunity to cooperate and work off their crime. And that’s a caustic, corrosive message to send. Many corporate law scholars complain that corporations have gotten the message that the law lacks teeth, because of the omnipresent cooperation loophole.

Abolish or reform?

HLT: Should we just get rid of this system altogether?

Natapoff: Years ago, I was asked to testify before the House Judiciary Committee about the informant problem. It was in connection with the murder of Kathryn Johnston, a 92-year-old grandmother in Atlanta who was killed by police based on a bad informant tip. As I was testifying, Congressman Jerry Nadler turned to me and said: “Professor Natapoff, why don’t we just ban informant use? Is that what you’re saying?” And I must admit that it took me off guard, because I did not expect a sitting congressperson to float the idea that we should just get rid of the institution altogether. So, here’s what I said and what I still think. There are two reasons — one small and instrumental and one large and principled — that I don’t advocate for getting rid of informants.

The small, instrumental reason is that we can imagine certain kinds of situations — political corruption, corporate crime, Wall Street corruption — in which the social costs of using informants might be relatively low, but the benefits of being able to go after high-level, powerful, well-insulated defendants is extremely high. You can imagine a public democratic conversation about the costs and benefits of those deals, especially since this is the most transparent space of informant use where we tend to find out afterwards what actually happened. If we really knew the full costs and benefits, we might, as a democratic community, decide that it’s worth letting the occasional inside trader off if they can net us a more responsible, accountable Wall Street. We don’t in fact run most of the informant market in this careful, transparent, lawyer-regulated way, but there’s certainly a space in which we might. So that’s the instrumental answer.

The more principled and structural answer is that, as long as we have plea bargaining, we are going to have informant deals. You cannot excise the dysfunctions of the informant market from the larger fact that we are running our entire criminal system as an enormous kind of negotiation. But we do not need to tolerate the radical deregulation of the informant deal. We do not have to tolerate its violence and its inequalities. We do not have to tolerate its opacity and lack of transparency. We don’t have to tolerate the fact that Congress has no idea how many serious crimes are committed by informants run by federal agencies. And so, my recommendation is not to abolish the practice; not because I think the practice is a good idea but because it’s endemic to a larger systemic choice that is beyond the scope of informant reform and this book. Instead, my recommendation is that we should stop tolerating the violence, the disparity, the unfairness, and the opacity of the current system.

HLT: In the last chapter of your book, you suggest a comprehensive set of recommendations for reforming the system. Can you touch on the biggest one?

Natapoff: One of the reasons I decided to write a second edition of this book is because so much has happened since I first wrote it 13 years ago. There’s been so much change in our understanding of and critical acuity about the use of informants. Some of it has been litigation. Some of it has been legislation. Some of it has been media attention. Some of it has been cultural change. There are many proposals for reform, but I think there are a few that we should focus on.

The most important is a general rejection of the culture of secrecy that we have permitted the informant world to take advantage of. For so long, law enforcement has told us without proof, without demonstration, that they need utmost secrecy to create and reward and run informants, and that this is the only way that they’ll be able to use informants to catch the big fish. And we know that not to be true. We know that more transparency, supervision, regulation, accountability does not defeat the government’s ability to use informants. Indeed, for all its flaws, the FBI has quite substantial internal and external regulations, and they run informants just fine. So, once we let go of the mythology of secrecy, then we can make sensible decisions about the kinds of data that the public and legislators and courts need to know.

We should also reject the omnipresent availability of the informant deal. Basically, the informant market is an enormous loophole to every criminal law passed by the legislature. The legislature says: “Don’t commit this crime. If you do, you’ll be sentenced to five years.” And the informant market says: “Unless you cooperate, in which case, all bets are off.” Legislatures have a strong incentive to understand which laws that they pass are being negotiated away. That calls for more data and more regulation.

We are still unable to have a meaningful cost-benefit conversation because the government doesn’t share with us the data regarding its informant practices. But we know more than we used to. When I first wrote this book, only a handful of states had engaged in reform in this space at all. Now over half of all states have either considered or passed informant reform, whether it’s greater disclosure, or tracking, or protections for vulnerable informants. In the same way that the nation is rethinking mass incarceration, we are rethinking the many tools of mass incarceration, and informant use is one of those especially problematic tools.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.