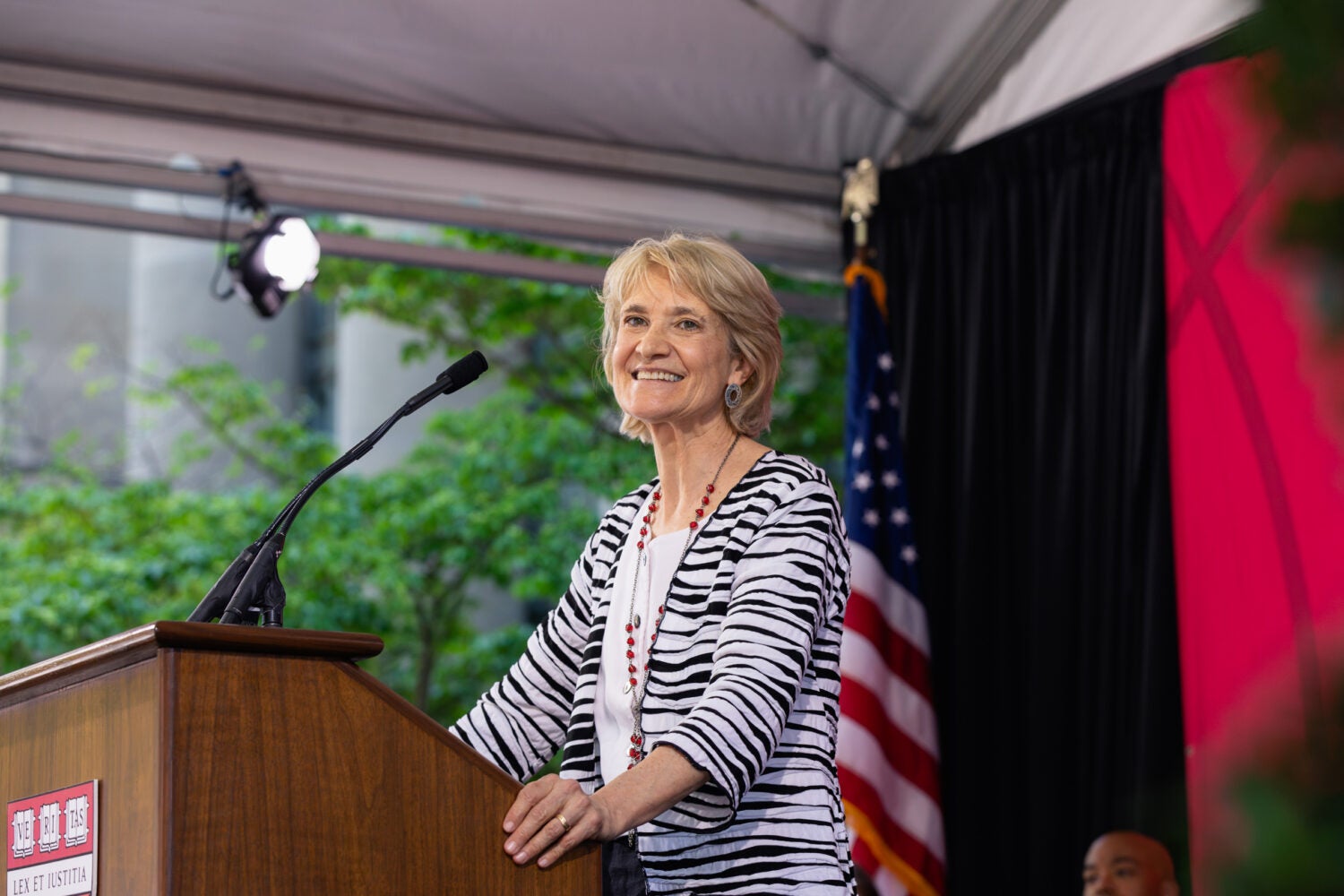

Christine Desan, the 2024 recipient of Harvard Law School’s Albert M. Sacks-Paul A. Freund Award for Teaching Excellence, congratulated the nearly 800 graduating students and thanked them from the bottom of her heart for the honor. Desan, the Leo Gottlieb Professor of Law, told the audience that the award was especially meaningful as it had come after having taught law for 30 years.

“You could say I didn’t peak early,” she joked. “But some projects are worth a lifetime effort,” she added, “and teaching has been that project for me.”

The Sacks-Freund Award, which is given to a faculty member each year for teaching ability, attentiveness to student concerns, and general contributions to student life at the law school, was established in 1992 and is named in honor of the late Harvard Law School Professors Albert Sacks ’48 and Paul Freund S.J.D. ’32. Looking out at the thousands of students, family, friends, faculty, and others assembled under the canopy of foliage across Holmes Field, Desan shared the three main takeaways she’s drawn from a lifetime of teaching.

First: “Build knowledge like a river.”

Information flows in many forms, said Desan. “We seem to take it in sequentially and cumulatively and weave it together. And we can do that deliberately in the classroom, but also in the courtroom in the conference room in organizing efforts. We can integrate streams of material over time,” she said, noting that in her classes, the streams often involve history, theory, and doctrine, and it often comes in many forms.

“So, we build in streams of material that we take in as background,” Desan explained. “And as we take in other kinds of sources, cases, texts, we diagram the dynamics of institutions, we think about the debates that tie together all those sources. And when we integrate those streams of material, we get something new, something rich. The river that results is different. It’s powerful. It’s an amalgam that departs from all its ingredients. It has a momentum of its own.”

And every year, Desan said, she recognizes the river, but it’s also new, the product of members of that class: “Their insights created something unique. “When knowledge becomes an event so exciting, you hang around teaching for 30 years.”

Her second takeaway from the classroom: “Experiment. Always experiment.”

Desan said every classroom is a laboratory and a space for experimentation (as is every courtroom, every meeting room, every conference, and every organizing effort.)

During her career as a teacher, she explained, she has employed a swath of different instructional techniques, from the Socratic method, to lectures, to free-wheeling discussions. One year, she institutionalized something called “mandatory volunteering” in a Civil Procedure class. It was a fascinating class, Desan said, “but the mandatory volunteering was a bit of a bust.”

Desan, who teaches about monetary and financial institutions, recalled how she once introduced in her class an exercise involving “bimetallism,” a government mandated exchange rate between currencies minted of different metals such as silver and gold coins, only to abandon it in subsequent years. The lesson, she recalled, “sent the entire class over the edge.”

According to Desan, that type of experimentation always “feels like a risk.”

“You never know if you have asked the question that will open up the right issue,” she said. “You never know if you can orchestrate the most effective discussion. You never know if you can build from that discussion to the doctrinal development or constitutional change you want to illuminate.”

“But while it feels like a risk, and I have had my share of missteps,” she said, “the real risk is that other way of teaching was tapped out, the other way of teaching didn’t work as well as it should, or the other way of teaching left the students in the cold.”

The same principle, she argued, governs the practice of law. Like in every classroom, she said, the point in every courtroom, legal brief, and organizing effort is to communicate effectively. “So, I would say experiment, always experiment in the interest of better communicating, and bring the results into your river of learning.”

Desan’s final takeaway is what she calls the McCullough rule, modelled after a decision written in 1819 by United States Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall in McCullough v. Maryland, in which the Court ruled that federal government actions are allowable as long as the means used are well adapted to constitutional ends.

“My students know I have reservations about some of his opinions,” she explained. “But he was right when he said that the means are where the action is. When he empowered Congress to use all necessary means, he gave Congress a power he deemed comprehensive.” Desan added, “our lives happen in the means, ever on our way to the ends.”

She told the audience that she has been obsessed with the means for a long time. She got her start at Harvard Law School teaching Civil Procedure, because it was the means of resolving disputes. She then moved to studying money and banking because they are the means we use to capture value and mobilize resources. “The means matter enormously, she stressed, and so does their design.”

Teaching is also a means, she added, and its design is consequential. For example, as a student she hated the Socratic method. As a teacher, she tried using it for several years, tinkering with it, but never warming to it. She came to believe it taught a specific set of lessons, some of them useful — including how to think on your feet — but also, she said, how to respond when spoken to, to impute the answer and maybe the advantage to the authority in the room, and to distill learning into a bilateral exchange.

“I realized I’m not so interested in teaching those lessons,” she said. Instead, she wants to teach her students how to choose the right moment to take the initiative, to use the opportunity to develop the answers, and to harness the combined wisdom of the classroom to solve problems more effectively.

She says she is not sure what to call the ensuing teaching method. “[I]t’s a different means, a kind of orchestrated discussion, or crowdsourced argument,” she said, “maybe the ‘River Way,’ using a metaphor appropriate for Boston.”

“I would go so far as to say that as we design the means we design the ends and as we redesign the means, we redesign the ends.”

In Desan’s favored approach to pedagogy, students participate in response to many prompts. They contribute individually and in concert. The outcome, she said, is a product of many minds “that no one person in the class could have accomplished but that we as a challenging, curious, driven, and very different set of lawyers could.”

Desan told the audience that, “If what I say strikes you as sacrilegious, don’t worry. The Socratic method is alive and well at Harvard Law School. It is just not my chosen means.”

In closing, Desan reminded the audience of the McCulloch rule — that the means matter and that we should choose the means to comport with our values. In fact, she said, “I would go so far as to say that as we design the means we design the ends and as we redesign the means, we redesign the ends.”

Celebrating the Class of 2024!

View full coverage from the festivities of the 2024 Class Day and Commencement Ceremonies at Harvard Law School.