Does the 14th Amendment empower states to keep Donald Trump off the 2024 presidential ballot?

As the United States Supreme Court gears up to hear arguments in Trump v. Anderson on February 8 — which will decide if Colorado may exclude the former president from the ballot based on the January 6, 2021 assault on the U.S. Capitol — experts at Harvard Law School’s Rappaport Forum led a spirited debate on a complex set of issues with profound implications for the upcoming election and beyond.

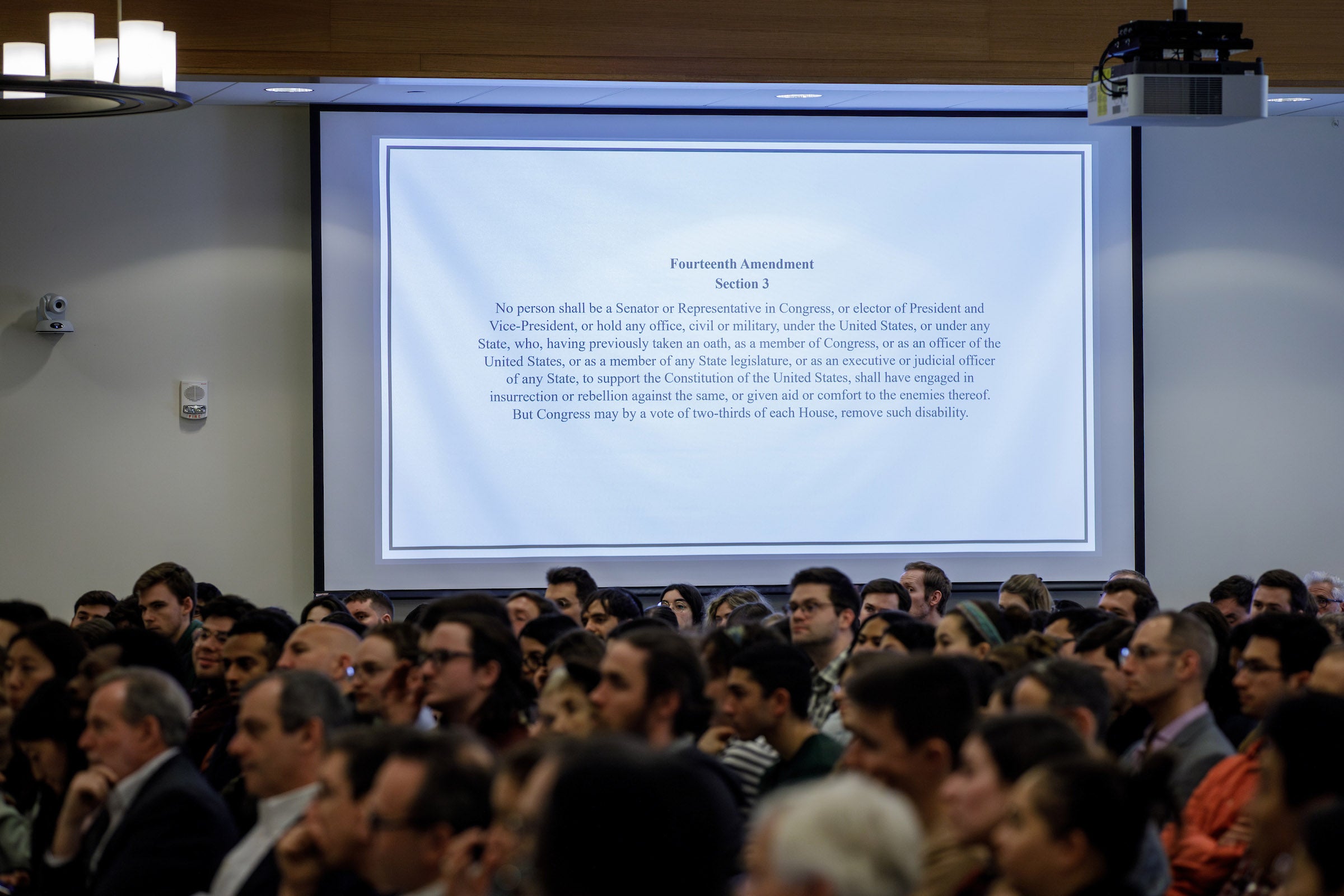

Thursday’s debate dove into the specifics of Section Three of the 14th Amendment, which bars from serving in Congress or “any office” — federal or state — those who have previously taken an oath as “an officer of the United States” to support the Constitution of the United States and nonetheless engaged in “insurrection or rebellion” against it. Critics contend that Trump should be disqualified for the presidency under the provision for his part in the events of January 6, and have challenged his eligibility to appear on the ballot in at least 30 states. In December, Colorado’s highest court agreed with this interpretation — a decision that was quickly placed on hold as the U.S. Supreme Court prepares to hear the case.

Moderated by Jeannie Suk Gersen ’02, the John H. Watson, Jr. Professor of Law, the panel featured Professor Akhil Amar of Yale Law School and Michael Mukasey, of counsel to a New York City law firm and former U.S. Attorney General and Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Gersen began by pointing out the tangle of legal issues the Court will soon consider. Does Section Three even apply to the president even though the office isn’t specifically mentioned, and if it does, is Section Three self-executing? Does it bar someone from running in addition to holding office? And, “even if one gets past all of these possible hurdles,” she added, who decides “whether Trump actually engaged in insurrection or rebellion”?

Yale’s Amar thought the first question was clear: “My side may well lose the case,” he said. “But I’d be surprised if we lose the case on the proposition somehow that ‘office’ and ‘officer’ don’t apply to Donald Trump.”

The 14th Amendment was ratified following the Civil War, Amar reminded the audience. “If you’re ineligible to be a judge or a justice or senator or representative, or, for that matter, a dogcatcher or cabinet officer — but you can be president of the United States and that’s no problem? Jeff Davis, president of the United States, or Robert E. Lee? Seems a little odd, to put it mildly.”

He pointed to language in another part of the Constitution as proof. “A quibbler might try to argue that the president does not strictly speaking ‘hold office’ of the United States and is instead a sui generis figure,” Amar said. But the text in Article II “provides that the president shall ‘hold his office’ for a four-year term.”

It also makes rhetorical sense, said Amar. “If my wife tells me to go to the store and get every brand of cookie, she doesn’t then say ‘Oh, and get Oreos.’” In other words, he added, “president” is “generically covered by the word ‘office’ and ‘officer’ and every single person who talked about this said that.”

“If you’re ineligible to be a judge or a justice or senator or representative, or, for that matter, a dogcatcher or cabinet officer — but you can be president of the United States and that’s no problem? Jeff Davis, president of the United States, or Robert E. Lee? Seems a little odd, to put it mildly.”

Akhil Amar

But Mukasey had his own historical evidence, which he said suggested that Congress had intended to exclude the presidency from Section Three. “Now that I’ve been cast as a quibbler,” he joked, “I’d like to go through the text and go through some other references in the Constitution.”

“A prior draft of Section Three did include the words ‘president or vice president,’ those were stricken,” he said, adding that “they were stricken with the knowledge of the person who sponsored the section.” Instead, he said, Congress was focused on preventing former Confederates from serving as senators and representatives.

Given that the amendment’s drafters explicitly mentioned members of Congress and electors of the president or vice president, “you would expect that if they wanted to include the president in that list, they would have done so, and in fact, as I pointed out, there was a draft that did so, and it was stricken.”

Mukasey highlighted other places in the Constitution’s text that seemed to support his view. “The impeachment clause — Article Two, Section Four — provides that the president, vice president and ‘all civil officers of the United States’ shall be liable for impeachment if they commit the requisite offense. It doesn’t say ‘all other officers’ of the United States, which suggests to me as a quibbler that the president and the vice president are not included within the category of ‘officers.’”

The case, and the issues it raises, represent an incredibly difficult moment for the country, said Gersen. Is there too much weight being put on a few words of text?

“A lot of weight to be putting on the text?” Mukasey replied. “The text is what constitutes this country. I have no hesitation at all putting the weight of everybody sitting in this room and multiples of that on the text, because the text is all we’ve got.”

Amar agreed about the importance of the text, but added that “text serves purposes, and texts have to be understood in context.”

Did former President Trump foment an insurrection?

Even if the presidency is included under Section Three’s provisions, there remains an even bigger, and more consequential issue, Gersen reminded the audience: whether former President Trump actually engaged in an insurrection or a rebellion — and who has the authority to determine that.

Quoting a Tenth Circuit decision by Justice Neil Gorsuch ’91 before he joined the Supreme Court, Amar said that “a state’s legitimate interest in protecting the integrity and practical functioning of the political process permits it to exclude from the ballot candidates who are constitutionally prohibited from assuming office.”

Each state will determine eligibility at different points, he added. Some will enforce it at the primary level, some during the general election.

“Should we be disturbed by the idea of all 50 states going at it and having all different standards of how they’re interpreting insurrection or rebellion?” said Gersen.

“Welcome to the Electoral College,” Amar quipped.

Mukasey insisted that the Supreme Court should be the final arbiter of what Section Three means. “I think Supreme Court law and precedent going back to Cohens v. Virginia and other cases, says essentially [that] the Supreme Court has the last word. And frankly, it stuns me to see the 14th Amendment, which was meant in the large to limit the powers of the states, being used as the occasion for scattering authority among 50 states to decide on 50 separate bases who’s going to be on the ballot and who isn’t.”

To Mukasey, Colorado’s specific process was also flawed. There was “not a whole lot of substance of the sort that judges and lawyers honor as a decision of a trial court,” he said, because the lower court based its decision on the work of the January 6 Committee without doing its own fact-finding.

Gersen then asked Mukasey who, in his view, gets to decide whether a candidate has committed an insurrection for the purposes of Section Three.

“My standard is conviction under the Insurrection Act in a real proceeding, a real trial in which witnesses testify and are cross-examined,” he replied.

“Can an event like January 6 grow into an insurrection? Absolutely. But a conversation over a kitchen table can also grow into an insurrection, and I think you need a limiting principle in order to apply that.”

Michael Mukasey

But that’s the wrong standard, countered Amar. “I’m very glad that you actually said, ‘a conviction is required,’ because they knew those words, and they purposefully avoided those words [in the amendment].”

So, did Trump engage in an insurrection? After all, he has not been indicted for such a crime, Gersen noted.

Look to what the prosecutors did with other January 6 participants, said Mukasey. “They did not prosecute them for insurrection. Can an event like January 6 grow into an insurrection? Absolutely. But a conversation over a kitchen table can also grow into an insurrection, and I think you need a limiting principle in order to apply that.”

Political speech — even “obnoxious, delusional speech” — is still protected, he said. “I’m somewhat troubled by the notion that you can take something that is, in my mind, not an insurrection, never had any danger of succeeding, and elevate it that way.”

It’s hard to compare January 6 to the Civil War, conceded Amar. But there were two insurrections in the 1860s, the first of which looked more like what happened in 2021, Amar said. And both events, he insisted, would have been top of mind when drafting Section Three of the 14th Amendment.

In closing, Gersen acknowledged the stakes of the issues before the Court. One side believes that disqualifying former President Trump is the most important pro-democracy ruling in recent history, she said. “And on the other side, we have others saying that if you disqualified Trump, that will only foment similar violence to what we saw on January 6 and lead to the ruin of our democracy.”

How should a democracy respond?

“We resolve that by looking at the ultimate democratic statement, which is the Constitution,” replied Amar. “They thought about all this and lived through it. And there’s wisdom there, and democratic wisdom, because that had to get two-thirds of the House and two-thirds of the Senate and three quarters of the states.”

Mukasey preferred to see the problem resolved “the old-fashioned way.”

“It is much healthier, and more hygienic, for the politics of this country,” he said, “that [former President Trump] be defeated in the polls than disqualified in this kind of proceeding.”

The Rappaport Forum is an ongoing series of dialogues supported by the late Jerome “Jerry” Rappaport ’49 M.P.A. ’63 and his wife Phyllis to promote and model rigorous, open, and respectful discussion of important issues.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.