Federal Indian Law Professor Matthew L.M. Fletcher, the Oneida Indian Nation Visiting Professor at Harvard Law, admits the government’s relationship to tribal communities is — and has always been — ‘complex.’ But while tribal communities have often seen their rights erode before federal courts, recent Supreme Court rulings may signal new hope for tribes and their members. According to Fletcher, this change is due in part to a newfound strategic ingenuity and improved access to information for tribal parties.

Fletcher, a leading legal authority on the complex relationships between tribal communities and the U.S. government, is a member of the Grand Traverse Band, and currently serves as chief justice of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, and the Poarch Band of Creek Indians. In a recent conversation with Harvard Law Today, he delved into the value of federal Indian law to J.D. students, new ideas about some of America’s oldest promises, and the preservation of customs and traditions still honored in tribal courts today.

Harvard Law Today: Can you share a little about the class that you’ve been teaching this semester, and why you think Harvard Law School students should take Federal Indian Law?

Matthew Fletcher: Absolutely — in Federal Indian Law, we talk a lot about federal statutes and Supreme Court decisions that run back to the founding of the United States. There’s a consistent flow of Supreme Court cases involving tribal or Indian Affairs from term to term, so there’s no shortage of cases to discuss. We cover the whole gamut of federal Indian Affairs laws that govern things like commercial transactions and the federal/tribal relationship, which is often governed by treaty rights. We talk about Indian Country jurisdiction issues. It’s a wide array of issues, there are a lot of complex relationships and competing interests.

Students should take the class if they’re interested in litigation because there tends to be an enormous amount of Indian law cases circulating in the federal and state appellate courts at any given time. Transactional attorneys should know that Indian Country economic activity totals well-over $50 to $60 billion a year. Most tribes — especially those that are in more rural areas of the U.S. — tend to be the largest economic engines of their region, the biggest employers, and the biggest governing entities. Tribes also tend to be at the forefront of litigation and regulation of the environment and of natural resources. I think that we’ve moved past treating Indian law as a niche — it’s in child welfare, land use and planning, economic activity … it’s just everywhere.

HLT: What does the United States owe Indian tribes? What duties or responsibilities does the United States have?

Fletcher: In terms of what’s owed, it’s a lot. Many tribes long ago signed treaties where they agreed to give up most of their homelands. My tribe, for example, signed a treaty in 1836 along with several other tribes where we gave up the land base of what is now about 1/3 of the entire state of Michigan. In 1836, that land was covered in old growth timber and massive amounts of white pine — an especially valuable species of tree ideal for building houses, ships, etc. Nobody knows exactly how much timber was on that land or how much that would be worth, but easily billions — if not trillions — of dollars. When we signed the treaty, we agreed to forfeit our land and its resources for a price of 10 ½ cents per acre. The treaty also included hunting and fishing rights on and off the reservation, and small reservations that were never actually established properly for us.

“I think that we’ve moved past treating Indian law as a niche — it’s in child welfare, land use and planning, economic activity … it’s just everywhere.”

This treaty also contained something major known as the duty of protection. The duty of protection is a promise by the United States, a guarantee of economic rights, political rights, housing, health care, education, natural resources — everything that we need to continue to survive. All treaties between Indian tribes and Congress include the duty of protection.

“Dark matter” is a term scientists use to describe a theoretical form of matter that we can only observe from the effect it has on gravity. We can’t see it, we can’t quantify it with precision, but we know something massive is there from the way things around it have been affected. The duty of protection is like dark matter. It may not be quantifiable in terms of money. It may not be explicit in every treaty, it’s often an implied legal right. But it’s a massive, underlying obligation that has a long history of legal recognition. As a matter of law, the United States owes a duty of protection to tribes. It’s an important lesson for my students to grasp, that there’s a lot more to these agreements than merely just the words on the paper. So, in terms of what is owed today, the duty of protection is a good starting point for characterizing the federal government’s obligations.

HLT: As it stands, does federal Indian law provide tribes an adequate means for asserting their rights, seeking justice, ensuring fair treatment? If so, what are those tools? And if not, what needs to change?

Fletcher: That’s a big question. Tribal leaders will tell you that every time they end up in the United States Supreme Court, the law is on their side. And all they ask is that the Court just simply follow its own precedents. And that’s all they ask for. Every time you hear a judge, lawyer or politician say Indian law is “difficult” or “confusing,” what they’re really saying is that we’re going to change something to ensure that tribal interests lose. That’s why when we lose, it’s like an extremely long, circular, big, winding long opinion full of word salad. Because at its core, Indian law is actually really easy.

Indian Affairs statutes are all supposed to be interpreted to the benefit of the tribe or Indian people. So, when federal law is at issue, courts are supposed to ensure that Congress hasn’t accidentally, or in a backhanded way, negatively affected tribal rights. I call these the default interpretive rules of federal Indian law, that our laws favor tribal interests and are rooted in the duty of protection — a fundamental promise embedded in treaties signed with Congress that guarantees tribes economic rights, political rights, housing, health care, education, natural resources, everything they need to survive.

In a case called McGirt vs. Oklahoma, the key parts of Justice [Neil] Gorsuch’s majority opinion are about four or five pages long; it’s a really simple explanation. And then you read last term’s case, Arizona v. Navajo Nation, where Justice [Brett] Kavanaugh’s opinion goes on for 40-50 pages and I still don’t understand what the Court is saying. One of those cases was a win and the other was a loss. I bet you can guess which. So, the tools are technically adequate, but they’re not always as reliable as they should be.

“Every time you hear a judge, lawyer or politician say Indian law is ‘difficult’ or ‘confusing,’ what they’re really saying is that we’re going to change something to ensure that tribal interests lose.”

HLT: Speaking of McGirt v. Oklahoma, there have been a number of recent cases where the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of tribal parties, but in others — like Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta — the court has pulled back. Are we moving back or moving forward?

Fletcher: Things are certainly better, but that’s relative to an incredibly low standard from a historical context. The Supreme Court has been averse to tribal interests throughout the course of federal Indian law. Tribes have lost the vast majority of cases and, even when they win, all they’re doing is temporarily preventing their rights from eroding. Tribes know that when they’re before the Supreme Court, they can’t be there to advance tribal interests. They’re there to preserve the status quo or to limit their losses.

Since 2014, tribes have actually won a few cases. It’s probably the best 10-year period in the history of the Supreme Court. What ground have tribes actually won in that period of time? Outside of McGirt, not much. We won a huge generational case — the most important case that I worked on in my lifetime, Haaland v. Brackeen — that really just reaffirmed the law as it previously stood. That said, if you look back to the ’90s, tribes were losing 9-0 and 8-1 every single time. In the historical context anyway, things are actually looking better for Indian Country now than they really ever have.

HLT: What’s behind that overall net improvement in Supreme Court rulings relative to tribal rights? Have legal strategies evolved over time?

Fletcher: For the past 10-15 years, tribes have been cooperating with each other more and more. Prior to that time, none of the other tribes knew what each other were doing. Tribal attorneys weren’t talking to each other for a variety of reasons — they wanted to protect their tribe, and tribe trade secrets, or whatever.

Now everything’s out in the open and tribes know exactly what’s going on. As they get to working on a case that’s likely go to the Supreme Court, there’s already an informal organization of different kinds of advocates, including law professors, ready to meet and strategize how to actually win a case in the Supreme Court. That strategy is now highly organized and well-disciplined. That’s a dramatic change from the way cases were litigated before when the tribe that got in the Supreme Court would be all by itself, they kept their strategies to themselves, and a litany of repetitive amicus briefs would be filed because law firms can bill money to file them.

Now, there’s a strategy. Now, we know how to inform the Court about things that we want them to know about on the ground. We know we’re not going to win all the cases. We might not win even a majority. But a 5-4 losing opinion is a much more valuable outcome than a 9-0 losing opinion where the majority just can say whatever it wants. That really is a dramatic change. A 5-4 loss is way better than losing 9-0 for very concrete reasons.

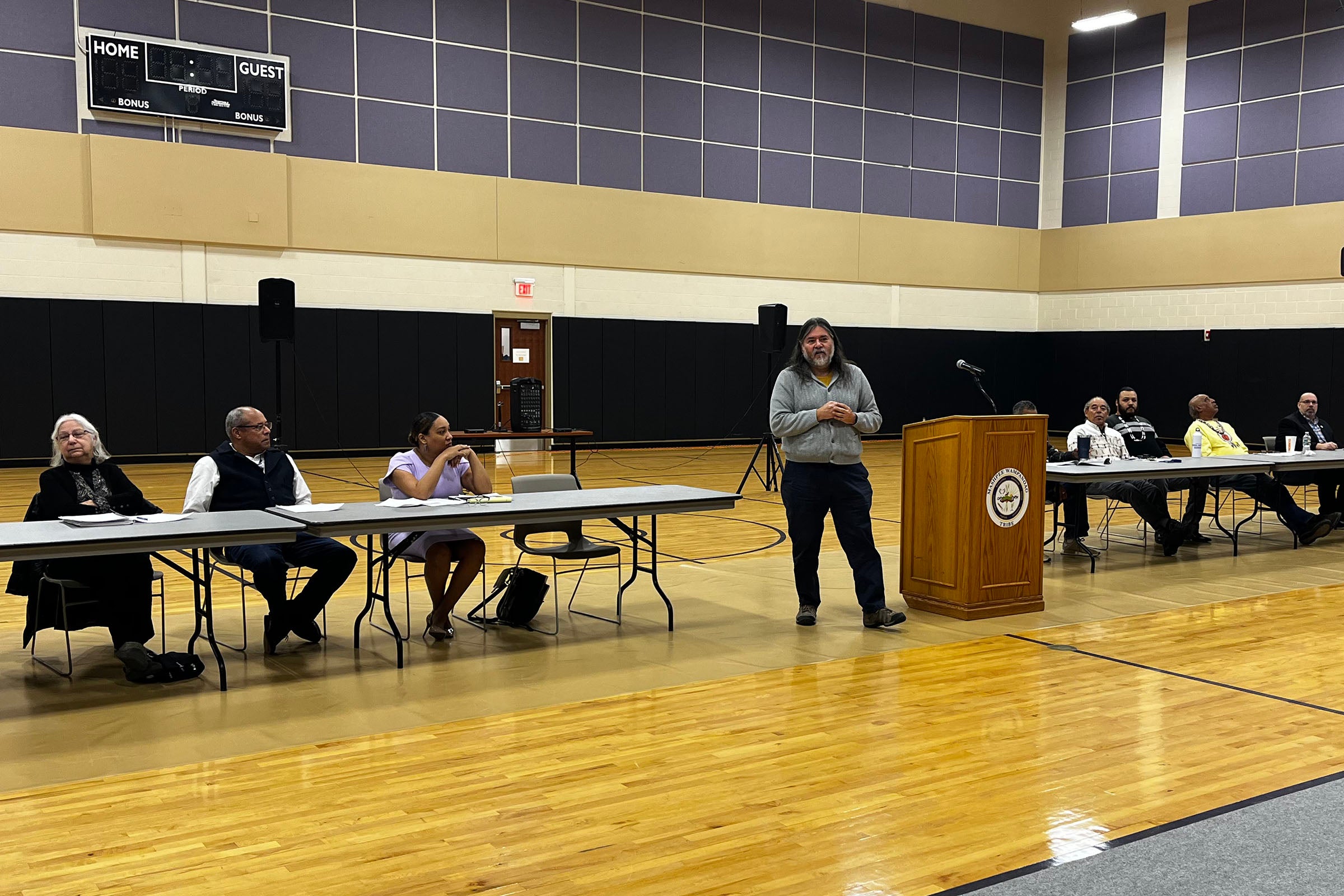

HLT: You recently took your class on a field trip to the Mashpee Wampanoag Courthouse — can you tell me about the visit and what you hope students will take from that experience?

Fletcher: Long ago when I started teaching law, I had mentors — people like Frank Pommersheim at the University of South Dakota — who would take students to a tribal court or reservation just to give them a sense of what it was like out there. I think it’s valuable for them to actually see in-person what a tribal government building looks like, what the reservation environment is like. The work legal professionals, practitioners, and technical specialists do for tribal governments is incredibly sophisticated and often done with pretty limited resources. It’s an experience that serves as a reminder of why we’re studying this topic, why advocacy is needed, and why the impacts of the cases we read matter.

HLT: Based on your experience serving as a tribal court judge for several tribes across the United States, what are some of the key differences in how cases are adjudicated on the reservation? Are there any aspects you think the rest of the United States court system could learn from?

Fletcher: One unique aspect in some tribal courts, like the one my class recently visited on the Mashpee Wampanoag reservation, is the presence of an elders advisory council. These councils are made up of tribal members who are elders — not judges or lawyers — and are actively informing and occasionally participating in proceedings. In my experience as an appellate judge for several different tribes, I’ve always appreciated having elders around to talk about the history of the tribe, the potential impacts any given decision might have on a tribe, what local issues might have led to the dispute. This information provides an enormously helpful context.

The Mashpee Wampanoag courthouse also has a peacemaking room. The peacemaking tradition originated in Navajo Nation, but it has been widely adopted by many tribes. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi in Michigan, for example, who I have worked with over the years, have circular court chambers made out of wood they milled themselves on-site and a peacemaking room in the shape of a circle with a firepit in the middle of it, which was hilariously hard to construct. Each direction of the building is represented by a different color of wood, which is also traditional.

HLT: Can you elaborate on the motivation or purpose behind the practice of “peacemaking” and its value to courts that use it?

Fletcher: The idea behind peacemaking is that it diminishes the adversarial nature of the whole legal process where one side wins, one side loses. A conference room is better than a courtroom, especially for the kind of disputes brought to tribal courts.

In federal court, the parties probably won’t see the other side again and won’t have to worry about crossing paths. Indians, on the other hand, live next door to each other in small, insular communities. From a community standpoint, the impact of adversarial process can be absolutely devastating — so it doesn’t fit, it doesn’t work for us at all.

Meeting to talk things out is a useful way to ease the tension that makes court proceedings more complicated and more difficult than necessary. That’s not unique to Indian people, that’s true for everybody. So even if “peacemaking” is aspirational, it can be extremely valuable.

“Meeting to talk things out is a useful way to ease the tension that makes court proceedings complicated … So even if ‘peacemaking’ is aspirational, it can be extremely valuable.”

HLT: The prevalence of violence against indigenous women and the disparate treatment their cases receive seems to be having a “moment” in popular culture right now, with “Killers of the Flower Moon,” Season 4 of “True Detective,” etc. But superficial awareness about a problem doesn’t always translate to meaningful change. What are the biggest barriers to addressing the MMIW [Murdered & Missing Indigenous Women] issue? And how can our legal system further the effort to overcome them?

Fletcher: That’s a great question. To unpack the MMIW issue, you have to start in the greater context of colonization where the United States intentionally and effectively destroyed tribal governance abilities. Most tribes had almost no functioning government by the 1970s. The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Service ran everything on reservations. Tribes starting at zero couldn’t automatically just buy a police force and suddenly have the ability to police the reservation. Tribes had to develop governmental capacity, the knowledge and experience on how to do this work and the actual resources to do it. But tribal governments lacked those resources having been chronically underfunded by Congress.

Then the United States Supreme Court in 1978 just decided out of the blue that tribes can’t prosecute non-Indians. That decision basically gave the entire non-Indian world notice they won’t be prosecuted in Indian Country. State governments don’t prosecute non-Indian crimes because states don’t have much of a police presence in Indian Country. The federal government doesn’t prosecute those crimes either due to a lack of political will or scarcity of resources. Your typical U.S. attorney is more focused on drug trafficking, domestic terrorism, kidnapping, and bank robberies — not domestic violence or misdemeanors in Indian Country.

I actually think the legal issues are pretty easy. The Supreme Court and its aggression towards tribes has created embarrassments for itself that are relatively easy to fix through congressional action. We simply need decisionmakers to demonstrate the political will to empower tribes with adequate funding. Lawyers can help as advocates in a legislative space, but it’s really daunting and really frustrating.

The truth of the MMIW issue is, it’s a matter of resolving the core societal ill behind violent crime and disparate access to justice — poverty. The main source of crime is poverty and Indian Country has a lot of poverty, more so than anywhere else. The glorious thing about tribes is that we know the answer to solving crime is the reduction in poverty. We can’t do anything to change that overnight, but we’re doing the best we can. We have already started to demonstrate that once we do get those resources, we can do some pretty dramatically amazing things. That’s finally starting to happen for a lot of tribal communities, but we have a long way to go.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.