On the stage of the Democratic National Convention, one Gold Star father invoked the words of the Founding Fathers, and just like that, a Pakistani-born Muslim-American lawyer led Amazon to sell more pocket Constitutions than ever before. His life has not been the same since.

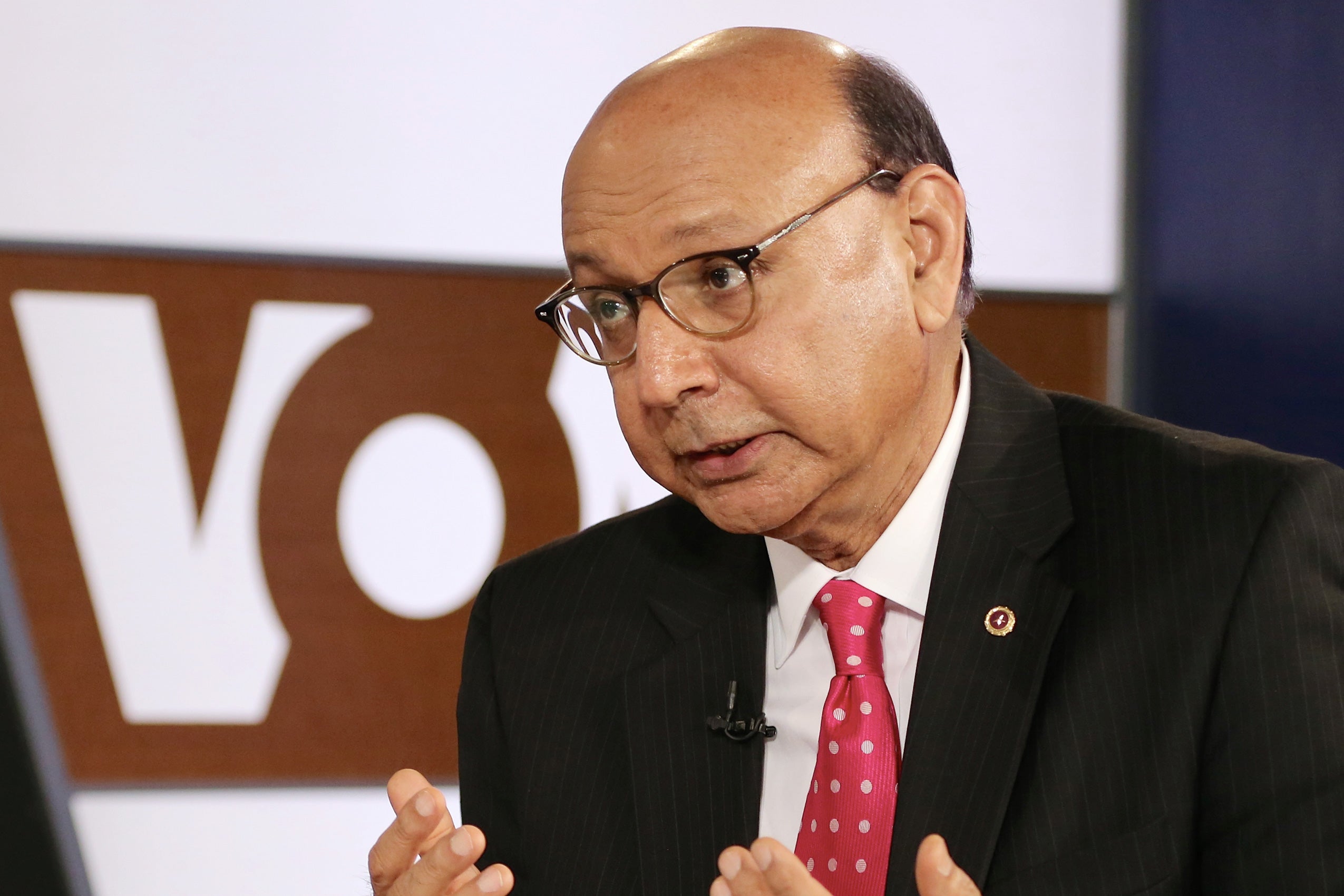

“Pre-DNC, was a very peaceful, private, quiet life, and I still enjoy that every time I get back to Charlottesville, but this mission is so important,” said Khizr Khan, LL.M. ’86, whose son Capt. Humayun Khan was killed in Iraq.

In a speech lasting six minutes and one second, Khan stepped out from behind the curtain of private pain and into the public spotlight, attracting worldwide attention.

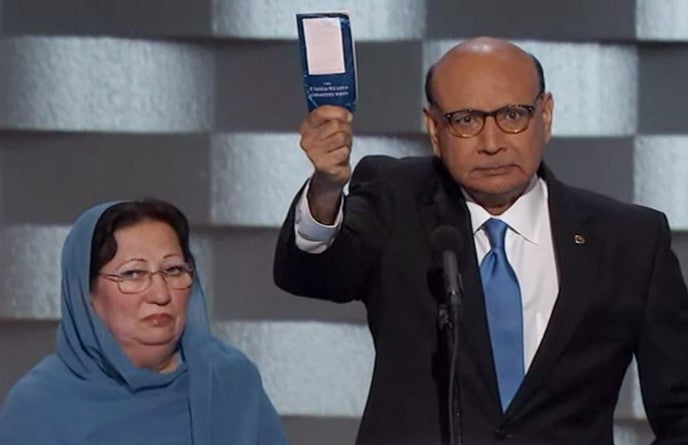

“Donald Trump, you are asking Americans to trust you with our future,” he said from the podium in Philadelphia. “Let me ask you: Have you even read the U.S. Constitution? I will gladly lend you my copy. In this document, look for the words ‘liberty’ and ‘equal protection of law.’”

These remarks propelled Khan headfirst into the 24-hour news cycle. In the weeks following the DNC, Khan appeared on nearly 40 news programs, received invitations to 18-plus speaking engagements for August and September alone, and fielded a growing list of book proposals, including one from Simon & Schuster. A Wikipedia page for him and his wife sprung up. His voicemail inbox beeped with both hateful and heartwarming messages, while his e-mail inbox was flooded with 4,000 messages and counting. Khan says he’s about 1,100 emails behind in thanking people, and that he’ll respond to every note personally.

“If one scared heart is strengthened by all of this,” said Khan, “it is worth it.”

He noted that his late son would be proud. “To him, one person mattered more than his own safety, more than his own value, anything. The same thing is with me. I get encouragement from his grace.”

Growing Up

Khan, 66, the eldest of 10 children, was born and raised in Punjab, an agrarian area of Pakistan, where his parents farmed poultry.

“We’re modest people, hardworking, always believed in education,” Khan reflected. “I wanted to study law from childhood. The reason was that leaders of the subcontinent at that time, all of them, had unanimously studied law, so that had left an imprint on my mind.”

Khan completed his B.A. from Punjab University in Lahore, and later, he attended Punjab University Law College, graduating with an LL.B. in 1973. There he met his future wife, Ghazala, who was pursuing a master’s in Persian literature. The two met at a book reading she hosted.

Following a nine-month apprenticeship with a senior attorney, Khan passed the bar and was licensed to practice in Pakistan. The job search led him to Dubai, where he found employment in the legal department of an oil company. There, the couple had their first two sons, Shaharyar and Humayun. The Khans’ son Omer would be born later in the United States, after the Khan family immigrated in 1980.

“The dream was that coming to the U.S. would be something to complete my education,” said Khan. “Harvard Law School was kind enough to accept my application and admit me to their LL.M. program,” he said, “and here we are.”

Harvard Lessons

At HLS, Khan was influenced by Abram Chayes ’49, his international law professor, and David N. Smith ‘61, then a lecturer on law and HLS vice dean. Khan recalled robust conversations on global affairs with Chayes, and spent hours with Smith, discussing the professor’s groundbreaking book on negotiating contracts in Africa. The two forged a friendship.

Smith, now a practice professor of law at Singapore Management University, says that he remembers Khan with much fondness.

“Khizr stood out and I think it was because of a remarkable combination of qualities: maturity, wisdom, modesty, and generosity of spirit,” he said. “I always came away from discussions with Khizr feeling that I had been in the presence of someone special. In life we sometimes meet people who teach others a lot just by being, and Khizr is one of those people.”

Khan was recently reminded of the meaning of his Harvard experience, beyond brick buildings and lofty libraries, during the Last Lecture Series, a collection of talks by HLS faculty, offering guidance to the graduating class. In one of the addresses, the professor asked, “What have you learned at Harvard Law School?”

“The only thing that came to my mind, the thing that remains true even today, was that Harvard Law School and Harvard University and its environment gave me the confidence in myself and showed me how little I know and that I should continue to make an effort to know more,” Khan observed. “That is what I carry with me every day.”

Life in the Law

Khan advanced into his legal career, becoming an expert in electronic discovery in commercial civil litigation. Looking back on his practice, two cases stick out in his mind.

The first, Silverstein v. St. Paul, was a behemoth. The central question was: For insurance purposes, did the 9/11 attacks in New York City constitute one occurrence or two? Billions hung in the balance. If it were one, there’d be a payout of $3.5 ; if two, it would be $7 billion. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit concluded that the collapsing of both World Trade Center towers was only one occurrence. Khan says this was the biggest case he ever played a part in.

The second case involved a dispute over the boundaries of Alaska’s territorial waters. At the time, now Chief Justice John Roberts, Khan’s then colleague at a major law firm in D.C., was awaiting his confirmation by the Senate, and he was still consulting on the case. One evening, Khan stepped into Roberts’ office, not to discuss issues, but simply to show him the marvels of the maps, which he had loaded onto a CD.

“So I took him that CD, and he said to me, ‘Khizr, this is my first technology lesson, so tell me how to open these documents,’” Khan said. “Justice Roberts was being modest and humble by saying that this was his first lesson in legal technology. I very fondly remember that conversation in his office.”

After Roberts left the firm for his seat on the Court, Khan often took his friends to a special spot in the firm’s office building, featuring a plaque mounted prominently on the wall behind a round table. It reads: “Here sat our friend, John Roberts.”

The Moment at the Microphone

Ghazala was in the doorway of the hotel room, ready to head out to the DNC, when a light bulb flashed on in Khan’s mind. He was fumbling through his suit jacket, checking that he’d removed any metal from his pockets, because he was told the DNC had tight security. Then he felt it—old faithful—his worn, pocket Constitution.

Khan often kept a copy tucked away into his breast coat pocket. Whenever he’d attend a formal event, he brought his conversation piece along. He also maintained a steady supply of copies at home, where he distributed the 52 pages of American law to whomever he could.

“Whenever cadets would come to pay tribute to Humayun at our house, and other guests as well, I thought it would be a good gesture to give them a copy of the Constitution because in the next day or so, they will be taking an oath on that document to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States,” Khan said.

So when Khan had dashed out of his hotel room and hailed a cab en route to the convention, the Constitution was all he could think about.

“Why don’t I say, ‘I will lend you my copy,’ and just pull it out?” Khan asked his wife, demonstrating by plucking it from his pocket.

“Look, the way you are pulling it out they can only see the back of it, which is nothing but just a blue page. That wouldn’t mean anything,” Ghazala warned. “So make sure when you pull it out, it comes out the right way!”

The rest of the ride, Khan practiced pulling out the prop in a way that they hoped make a powerful point, but not distract from his message: “that the citizens of the United States cannot be discriminated against based on their religious beliefs.”

Following Trump’s announcement of a proposed ban on Muslims from entering the United States, a reporter interviewed Khan, who described the 10 brave steps his son took before his death. The Clinton campaign caught wind of this article, and on the campaign trail in Minnesota, the Democratic presidential nominee called Humayun Khan “the best of America.” Shortly thereafter, Democratic Party representatives invited Khan to share his story on the DNC stage.

The Khans were initially asked to pay tribute to their son, and appear on stage briefly to accept Humayun’s honor, as is customary for parents of a fallen soldier. Later, they were asked to share a few words, and Khan wrote a lengthy six-page piece that his wife whittled down to one page, a mere 287 words.

While Khan has read most of Professor Laurence Tribe’s constitutional law books cover to cover, he never could have expected he’d emerge as the embodiment of American rule of law. Even still, he’s always had the words of the Founding Fathers close to his heart, literally, resting on his chest. And reading Section 1 of the 14 Amendment still moves him to tears.

“I didn’t know that I’d get so emotional reading the ‘equal protection of law’ words in front of people,” Khan recalled. “I had to compose myself. It has such an impact. I know what these words mean, and that is why I get emotional.”

A Civic Mission

One week later in Washington, D.C., Khan assumed the podium again in a packed hotel ballroom at a gathering for the Muslim Pakistani-American Physicians of North America. More than 3,000 doctors and their families arrived, but due to capacity, only 500 could be in the room at a time. People, including young children, spilled into the hallway.

Not a single person left until they took a picture with Khan. The selfies, hugs, and heart-to-heart conversations extended past 2 a.m., with many young people staying up far past their bedtimes, as if to catch a glimpse of history.

“What that tells me is that there is need for encouragement,” Khan said. “My message to them was that, ‘Look, in history we stand at a juncture where each and every one of us has to stand up and be the ambassador of good citizenship. That means do your best within your capacity, within your school, within your family, within your community, whatever good you can, a gesture of goodness.” He concluded by encouraging everyone to register to vote and participate in the political process.

With Islam as his North Star, Khan has been inspired to unite people of all faiths, races, and genders, and to amplify the voices of Muslims who have been “misdefined.” Some conservative critics have alleged that Khan has promoted Sharia, or Islamic law, above American law, which Khan denies.

“They need to read the Constitution. It has safeguards,” he said. “Sharia laws that people say are going to be imported to the United States and are a threat to society and all of that, no way.”

“I’m an ordinary Muslim, and I participate in all of my civic duties. I am a protector of the United States… My son gave his life, sacrificed his life in protection of the United States and its soldiers,” Khan continued. “Islam has taught me to be caring, to be kind. My religion is to live peacefully with all other religions and all other peoples.”

In Arlington National Cemetery rests Capt. Humayun Khan’s gravestone, carved with the crescent and star of Islam. Encircling the stone is a wreath, with bright bursts of blossoms in red, white, and blue, and to the left, a star-spangled flag.