On Friday, April 3, President Donald J. Trump fired the intelligence community inspector general, Michael Atkinson. Last year, Atkinson had, in accordance with a federal whistle-blower law, disclosed a whistle-blower complaint to Congress contending that the president had attempted to force the Ukrainian government to announce investigations into political rival Joe Biden. The whistleblower complaint ultimately led to congressional proceedings in which the president was impeached by the House of Representatives but acquitted by the Senate.

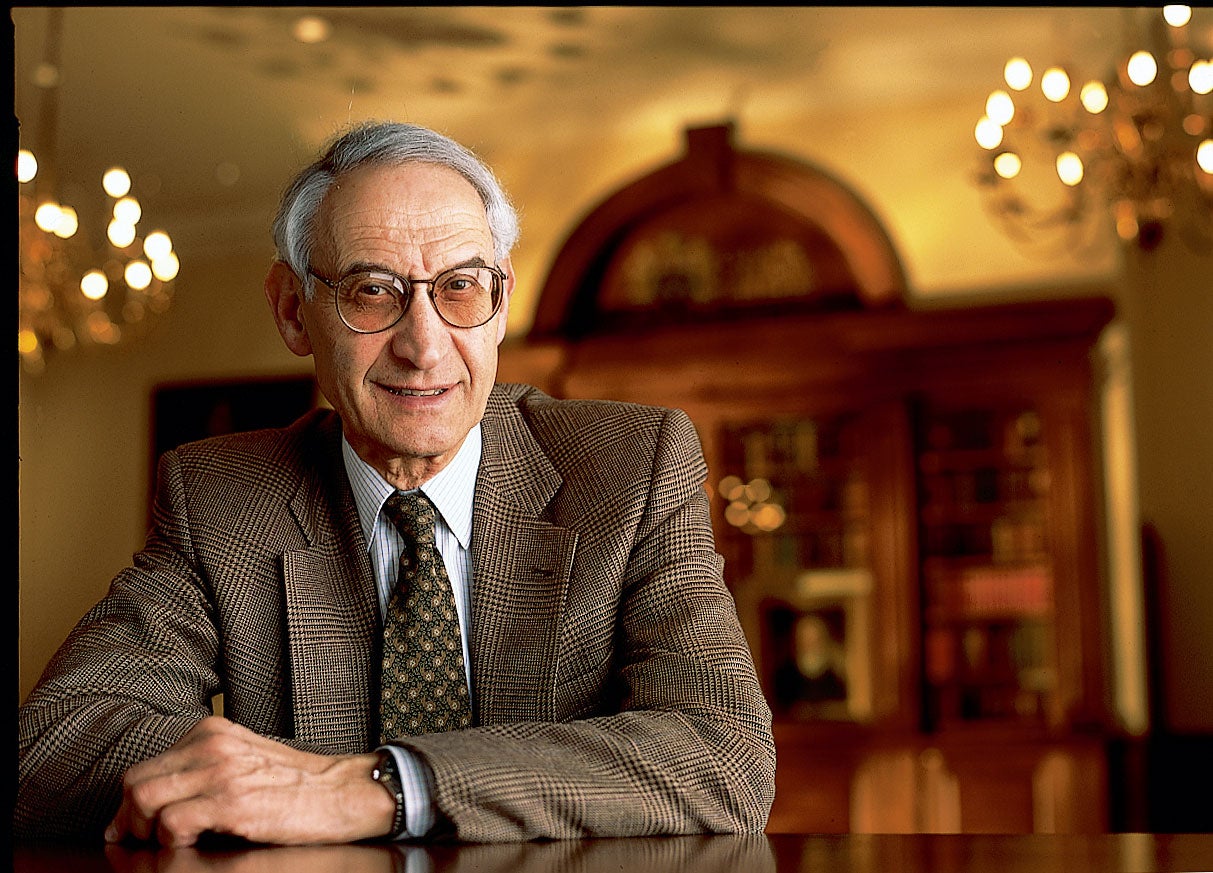

Earlier this week, Harvard Law Professor Charles Fried, who served as solicitor general under President Ronald Reagan, joined 21 other conservative or libertarian attorneys in a statement condemning Atkinson’s ouster as part of what they describe as a “continuous assault on the rule of law.” Only days later, the president also removed the acting inspector general at the Defense Department, who had recently been appointed by his colleagues to lead the panel Congress created to oversee more than two trillion dollars in emergency pandemic spending. Harvard Law Today spoke with Fried by email about why he believes these decisions represented a “contempt for the rule of law,” and about the implications for American government.

Harvard Law Today: In your view, why is President Trump’s decision to fire Michael Atkinson so troubling?

Charles Fried: Inspectors general are ubiquitous in the executive branch. Their office in each case is provided by statute, as are its duties and the term of its tenure. Atkinson’s appointment did not have a “for cause” removal clause, and that usually means that the appointee serves at the pleasure of the appointing authority—in this case the president; i.e. the appointing authority is free to remove the appointee without providing a judicially cognizable cause. President Trump cited his Article II duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed, which clause has been taken to imply he has full discretion to assure that his subordinate officers are indeed assisting the president in fulfilling that duty.

It is frequently the case, and was the case here, that the statute creating the office sets out its duties and authorities. These then become among the laws that it is the president’s duty faithfully to execute—the statutory officer therefore derives his power from the laws setting up and defining the authority and the president’s general duty that these, like all other laws, be faithfully executed. A presidential officer, say an inspector general, could not prosecute crimes because that is not within the authority the statutes grants. Nor, if the statute directs that certain actions be taken, the officer cannot decline to fulfill that statutorily prescribed action. This was established as early as Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 158 (1803)(Per Marshall, C.J.):

“This is not a proceeding which may be varied if the judgment of the Executive shall suggest one more eligible, but is a precise course accurately marked out by law, and is to be strictly pursued. It is the duty of the Secretary of State to conform to the law, and in this he is an officer of the United States, bound to obey the laws. He acts, in this respect, as has been very properly stated at the bar, under the authority of law, and not by the instructions of the President. It is a ministerial act which the law enjoins on a particular officer for a particular purpose.”

So, in the case of I.G. Atkinson, the question is one of law: did Atkinson act within his statutorily defined authority and was “a precise course accurately marked out by law.” If so, it was his “duty…to conform to the law, and in this he is an officer of the United States, bound to obey the law.” The president did not give a reason why he had lost confidence in Atkinson, but if that reason depended on the fact that Atkinson had followed exactly the letter of the law defining his authority and his obligations, then Trump acted on the incorrect premise that it is the duty of his officers not to follow that law but to act in ways that please him, even if that means neglecting a duly prescribed statutory duty. That is a premise of a tyrant, not of a constitutionally elected chief executive.

To put it succinctly, the president is enjoined to take care that the laws be faithfully executed. That adverb is not a part of this president’s vocabulary. Apart from that, and a very few very significant express or implied powers, the president’s authority is derived wholly from law.

HLT: Can you discuss the role of the inspector general for the intelligence community, and of inspectors general more generally?

Fried: I am not steeped in the law and lore of the intelligence community, but the duty of inspectors general in general is basically a kind of audit and report function. It is a function meant to ensure that officers and programs conform to the statutory provisions setting them up. In this, they are frequently viewed by administrations with great hostility—because they may present early stage ideas as fixed policy or distort the intricacies of administration to the unfair prejudice of officers trying their best.

In extreme cases such behavior would indeed be grounds for dismissal. When working properly, however, they are a similar kind of annoyance as the Freedom of Information Act or Open Meeting laws: the public and the legislature find out things about their government that the officers would rather they did not know. Once again, the premise of tyrants.

HLT: Since you and your colleagues issued your statement on April 7, President Trump removed, Glenn Fine, who had been on course to chair the new Pandemic Response Accountability Committee to oversee $2.2 trillion in new congressional spending. What is your view of that decision?

Fried: Congress insisted on an IG for this unprecedentedly enormous appropriation because, without some transparency, in the hands of partisan or corrupt officers it could be used in an election year as a slush fund to help friends and harm enemies.

HLT: You describe the decision to remove Mr. Atkinson as being part of a “continuous assault on the rule of law.” What are the implications of this “assault” for the long-term health of our governmental and political systems?

Fried: This action and the president’s justification fit perfectly in this president’s crude, proto-fascist conception of his own power, in which loyalty is due not to the laws and the constitution but to the person of the president, a view presented with only a bit more subtlety by his Attorney General. James Madison’s view, it is not.

HLT: How do you respond to the view that the president has the right under the law to hire and fire executive branch personnel, including inspectors general?

Fried: He has that power under the take-care clause. The adverb “faithfully” is an intrinsic part of that clause. But it is not an adverb that can be enforced in a regular court proceeding. In my judgment, however, it goes to the very essence of Congress’s power to impeach and remove.

HLT: What signal does this send to other inspectors general throughout the federal government?

Fried: The signal is an obvious one, and if any official didn’t catch it, the president’s media megaphone will make sure they don’t miss the point. As to how government officials should react: do your job honorably, truthfully, indeed faithfully. If you get fired for that, so be it. To quote Coriolanus, “There is a world elsewhere.” Somewhere there should be a monument honoring those who loved their country and the constitution more than their jobs.