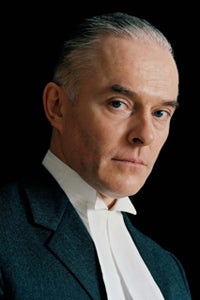

In a lecture sponsored by the Human Rights Program and International Legal Studies at Harvard Law School, Andrew Cayley, co-prosecutor of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge Tribunal, discussed his role as counsel on both sides of the aisle in international law.

“I’ve spent 16 years now in this field prosecuting and defending and also leading a number of investigations,” Cayley said.

Prior to joining the prosecution team for the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Cayley served as a defense attorney for Charles Taylor, the embattled former president of Liberia. In his remarks, he explained why he enlisted with the defense after many years serving in the prosecutor’s chair.

“In all of these courts, people must be properly defended in order for them to have legitimacy. I’m obliged to appear before any court in front of which I profess to practice. I also think that the experience of defending has made me a much better prosecutor, much more careful about the exposure of exculpatory material.”

During his talk, Cayley focused on his service as senior prosecuting counsel for the International Criminal Court. In this capacity, he led investigations into Sudanese officials responsible for genocide in Darfur, including high-ranking official Ahmed Harun and Janjaweed militant Ali Kushayb. When he landed this job, Cayley had just completed 5 years as the lead prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, where he charged the first members of the Kosovo Liberation Army.

At Harvard Law School, Cayley primarily discussed the nature of his investigation into Sudanese abuses of human rights and atrocities. The Darfur case, which the U.N. Security Council had referred to the court, was about “an ongoing human catastrophe [in which] the Sudanese were literally dropping improvised explosives on villages of their own people.”

The government also arrested and imprisoned citizens who were not murdered at the hands of the rebels. According to Cayley, it is estimated that more than 7 million Sudanese have been displaced “in an environment in which people starve to death.”

“It was a very challenging investigation because the Sudanese refused to collaborate with the court.” Nonetheless, Cayley and his investigators found remarkable first-hand accounts and medical documents to substantiate charges of crimes against humanity, including those committed by Omar al-Bashir, the country’s president.

The most harrowing evidence that the investigative team acquired was from a young Sudanese doctor who witnessed multiple rebel gang rapes of children at a girl’s boarding school in the country. She ultimately reported what she had seen, but not before the government’s intelligence service deployed rebels to brutalize her as a warning to keep silent.