Forty acres and a mule. The order by Union General William T. Sherman in January 1865, just after the Civil War ended, to offer some recompense to newly freed slaves for the harms they had suffered was a radical, tantalizing promise that never came to be.

More than 150 years later, the question of whether nations that benefited from the African slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries bear a responsibility to provide financial reparations for their crimes — as well as the lasting economic, social, and political damage they caused — remains unsettled. Many political and Civil Rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., have tried to gain traction for the idea periodically over the years, without much success.

Now may finally be the time. The issue caught fire again in the United States following author Ta-Nehisi Coates’ powerful and provocative 2014 polemic, “The Case for Reparations,” and the flourishing of the Black Lives Matter movement. Earlier this month, the state of Delaware issued a formal apology for slavery and Jim Crow-era laws, while a human rights panel at the United Nations pressed the United States to make reparations, blaming the effects of slavery for the many challenges still facing African-Americans.

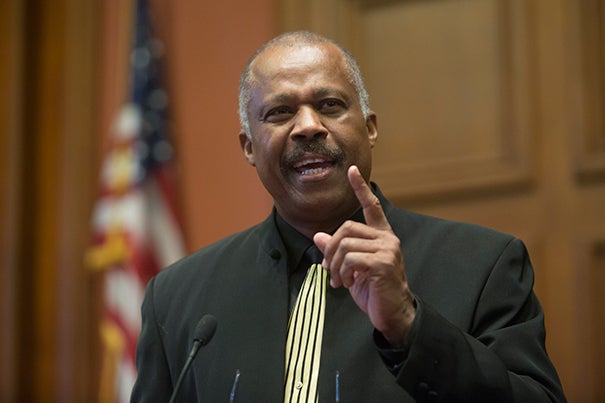

“This is not about retribution and anger, it’s about atonement; it’s about the building of bridges across lines of moral justice,” said Sir Hilary Beckles, a distinguished historian, scholar, and activist from Barbados, during a talk Monday at Harvard Law School, where tensions continue to roil over how best to confront racism and the vestiges of the School’s own historic roots in the slave trade.

Beckles is leading an international legal effort now underway in the Caribbean to hold European nations that engaged in that region’s slave trade accountable to the modern-day descendants of those slaves. He chairs a reparations task force of the Caribbean Community Secretariat (CARICOM), the region’s top political and economic body, that has made legal claims through the U.N. against the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Unlike past payments to survivors of the Holocaust, so far no nations have agreed to make restitution for slavery.

“Those who argue against reparatory justice, when you examine the assumptions of those arguments, whether legal, philosophical, social, moral … they converge around a simple point: that the African peoples of the Americas might have a moral and legal right to justice, but they are not deserving of reparatory justice,” Beckles said, “unless they are facing human extinction.”

Despite their united and longstanding opposition, it’s not as if European countries have never engaged in reparations, he said. After Haiti won its battle for independence in 1804, France demanded it be paid 150 million francs, a still-crippling debt, for its economic losses in exchange for recognition as a sovereign nation. Beckles’ own research found that Britain had made reparations for slavery in Jamaica — to the families of former slaveholders. Last year, he called for Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron, himself a descendant of slaveholders, to pay billions of pounds to Jamaica for its extraction of the tiny island nation’s natural and human assets.

Beckles says the call for reparations is directly related to the Black Lives Matter movement. During 17th and 18th centuries, slaves had monetary value to their owners, so laws were enacted to protect that value. Colonial governments compensated owners if slaves were somehow harmed.

“Nothing mattered more than black lives because their economies were built upon black lives,” Beckles said following an introduction by Sven Beckert, the Laird Bell Professor of History at Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) whose acclaimed 2014 book, “Empire of Cotton: A Global History,” traced the commodity’s primacy and how it inextricably bound Africa, Europe, and the New World in the 19th century. “The inventories of their estates, the productive structures of this country and all the Caribbean countries, the accounts, the balance sheets, all showed that outside of land, the most valuable asset on the books of every enterprise was black life, and therefore, black life mattered most.”

But with emancipation across the Western Hemisphere, black men and women’s utility in creating wealth for plantation owners suddenly evaporated, and black lives were no longer important.

Beckles, as vice chancellor of the University of the West Indies, asked President Obama to join CARICOM’s efforts and establish a U.S. commission to examine the idea of reparations during his visit to Jamaica in April 2015. He recalled the eerie symbolism of the accidental excavation of human bones from a slave graveyard during construction of a new building on campus.

“I felt the sense that there was a connection between this history and the present — the fact that our ancestors’ bones were being dug up as the president was coming to our campus,” he said, urging the HLS community to help push the United States to use its global influence to push reparatory justice as a matter of civil rights in the 21st century.

“Let us turn this history around. We cannot bury it because when we bury this history … the bones are everywhere. There’s no point in burying the legacy and the memory as well as the bones. Let us bring everything to the surface and find a way forward through all of this.”

Vincent Brown, the Charles Warren Professor of American History and Professor of African and African American Studies at FAS; Annette Gordon-Reed, the Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History at FAS; and Kenneth Mack, the Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law at HLS, considered the practicality and applicability of the Caribbean approach in the United States.

“Even if we zero in on the state, I fear that the demand for reparations presumes and depends upon states committed to distributive justice, a commitment most states haven’t borne since the rise of neoliberal governance, which, many would argue, is essentially predatory itself,” said Brown.

Gordon-Reed, who is also the Carol Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute and professor of law in the faculty of law, noted the differences in the way Europeans and Americans view and understand slavery. One important obstacle that must be overcome before the idea of reparations will go anywhere, she said, “is to make people understand that slavery was not just a system of holding people in bondage, it was holding people in bondage for a purpose, and that was to make money, to make money off of their bodies, and that’s the important realization that Americans have to come to.”

Rather than taking on the difficult task of trying to identify specific harms and the descendants of those who lived hundreds of years ago, it would be more practical to make whole those still alive who have endured slavery’s effects, such as disenfranchisement or housing discrimination, and then work back into history, she said.

“We can think about what we should do if we understand that all of us benefit from the proceeds of slavery every day if we’re associated with this institution,” Mack said in response to repeated questions from HLS students about how to confront the School’s racist history and prompt change on campus.

Mack and Gordon-Reed noted the many real-world opportunities in Boston and across the United States that exist right now for HLS students to facilitate getting reparations for black people through the legal system.

“All of us derive a present-day benefit from the oppression, the degradation of human beings. And what should we do as an institution to make reparations for that” is what should be on everyone’s mind in thinking broadly about the concept of reparations, said Mack.

This article was originally published in the Harvard Gazette on February 26, 2016.