Students use Harvard Law School Library’s Historical & Special Collections to analyze intent

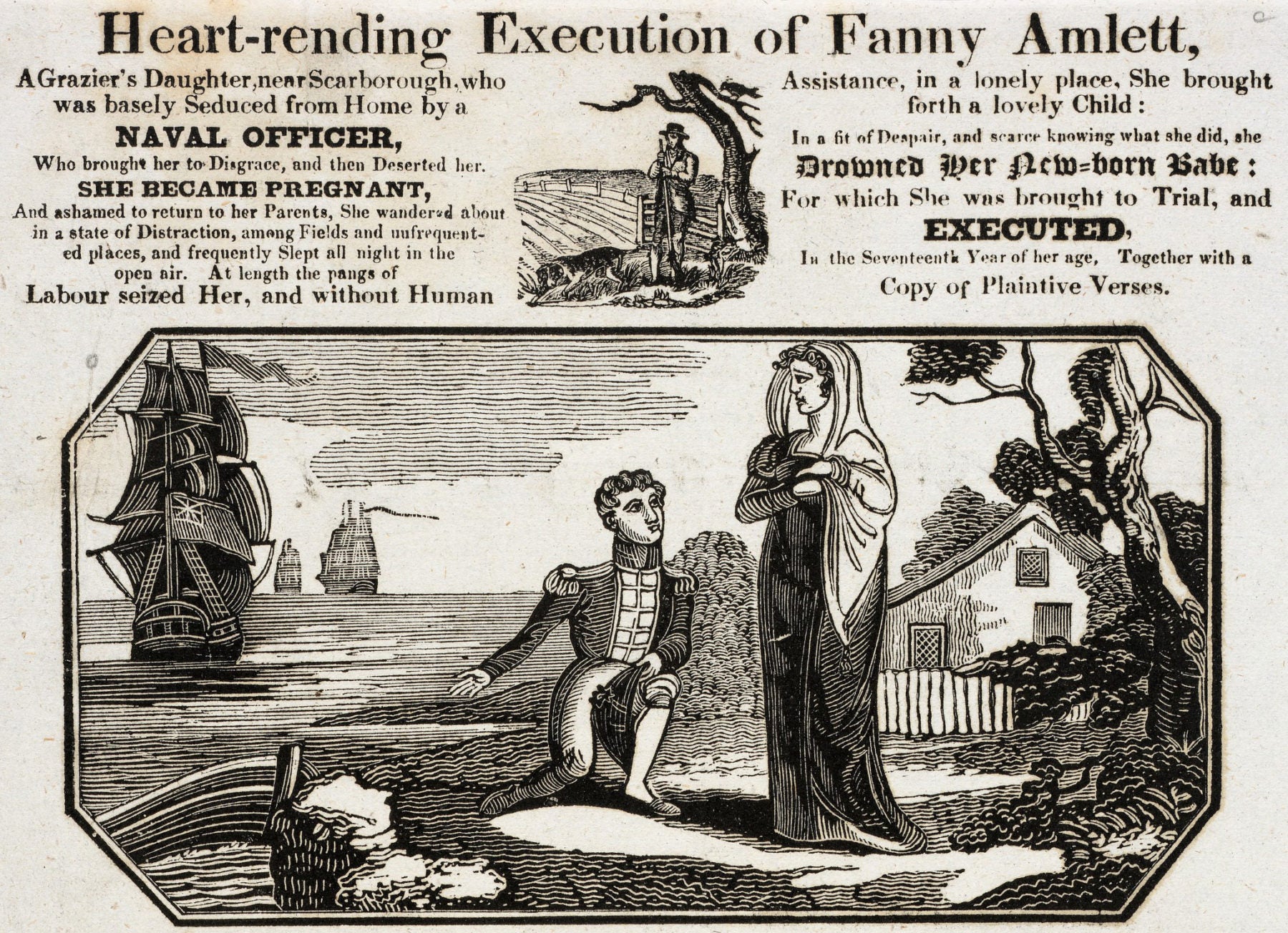

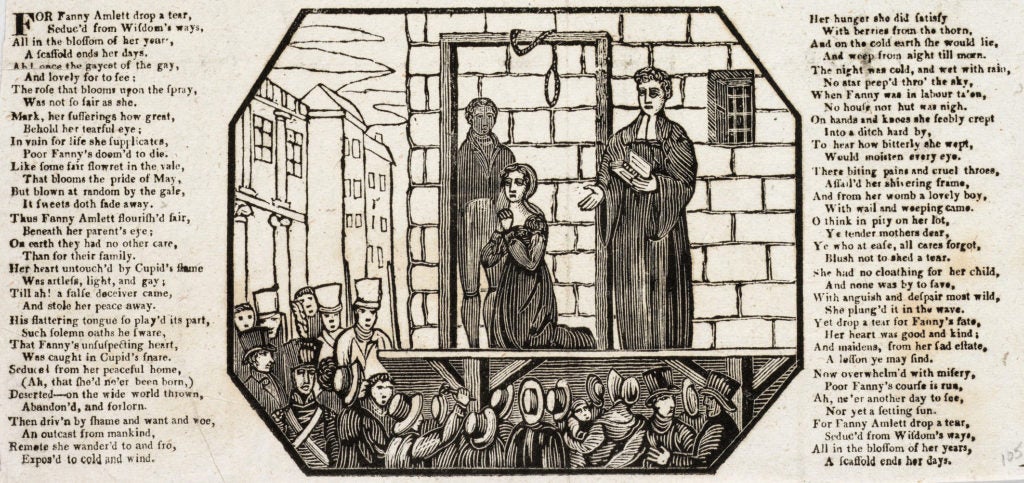

Detail from the broadside of Fanny Amlett, who was tried and executed at the age of 17 for drowning her newborn child. The ‘Dying Speech,’ as these execution broadsides were more generally known, reads: ‘Heart-rending execution of Fanny Amlett: a grazier’s daughter, near Scarborough, who was basely seduced from home by a naval officer, who brought her to disgrace, and then deserted her. She became pregnant, … in a fit of despair, and scarce knowing what she did, she drowned her new-born babe: for which she was brought to trial, and executed, in the seventeenth year of her age, together with a copy of plaintive verses.’ Credit: Harvard Law School Historical & Special Collections

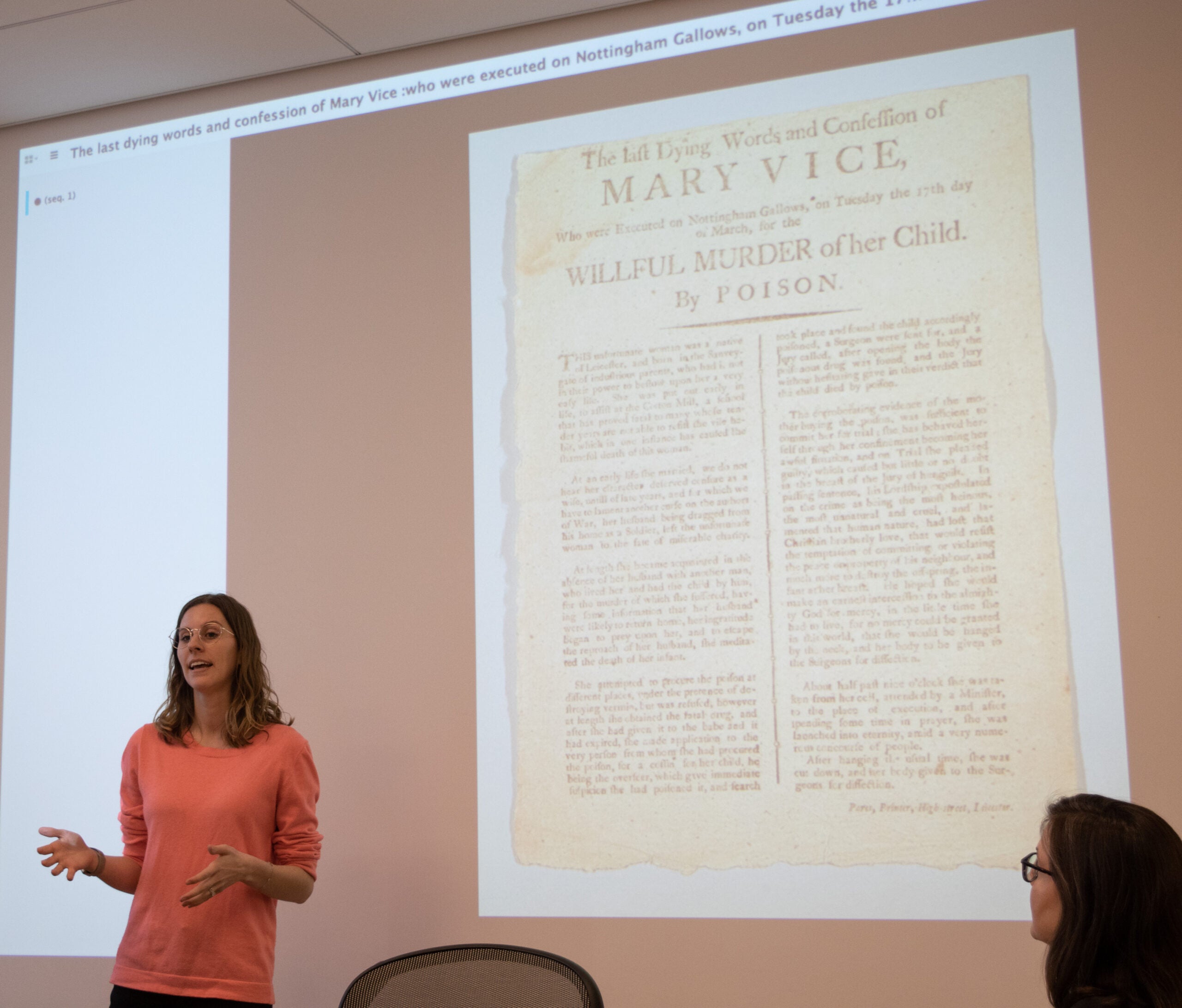

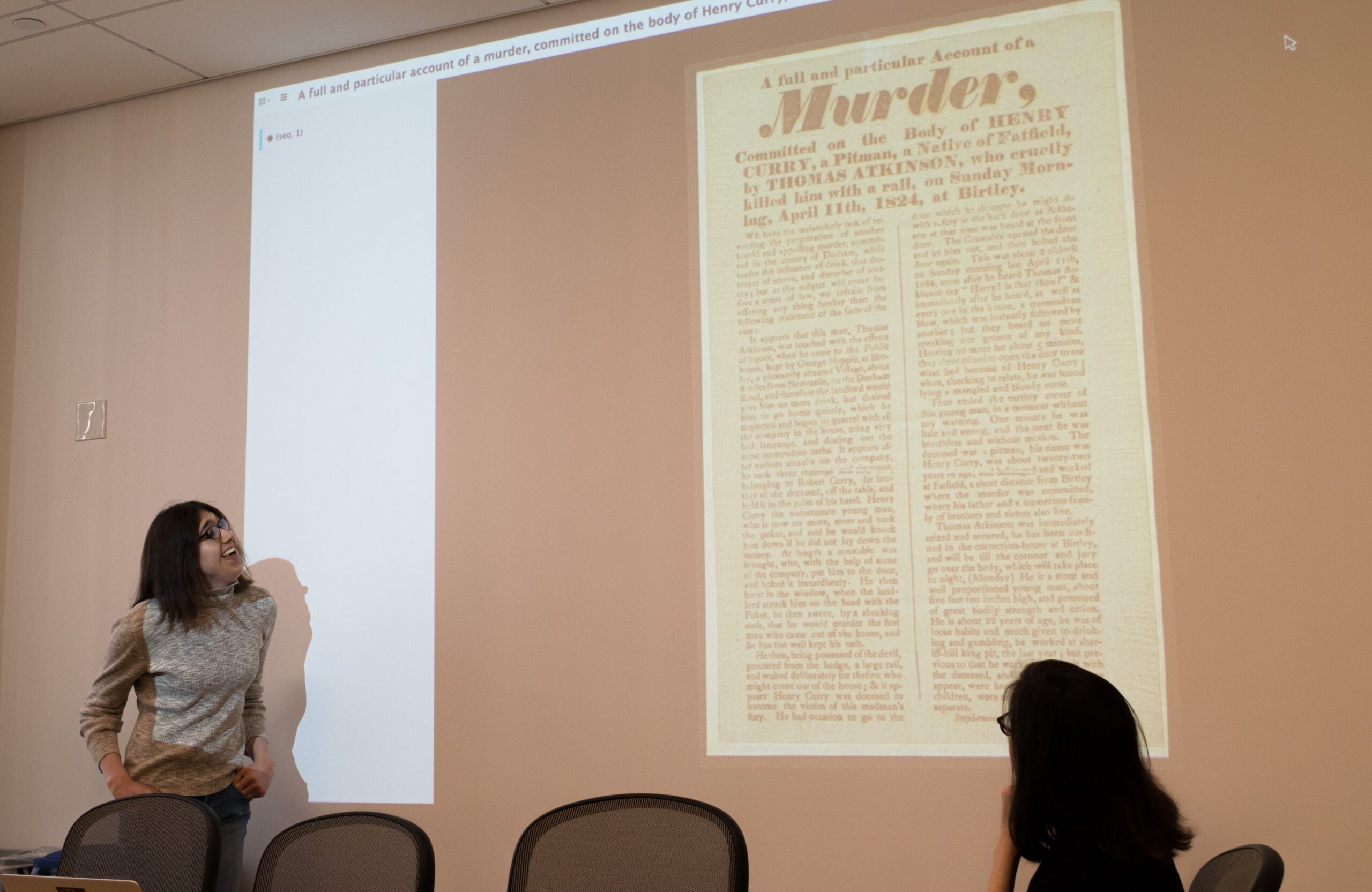

Students in Professor Elizabeth Papp Kamali’s seminar, Mind and Criminal Responsibility in the Anglo-American Tradition, spend the semester reading and analyzing primary and secondary sources—beginning with Jewish scriptures and excerpts from Roman law through the end of the 21st century—to study the history of mens rea in English common law. (Mens rea refers to criminal intent, the state of mind statutorily required in order to convict a particular defendant of a particular crime.) One of these primary sources—crime broadsides—can be found in the Harvard Law School Library’s Historical & Special Collections.

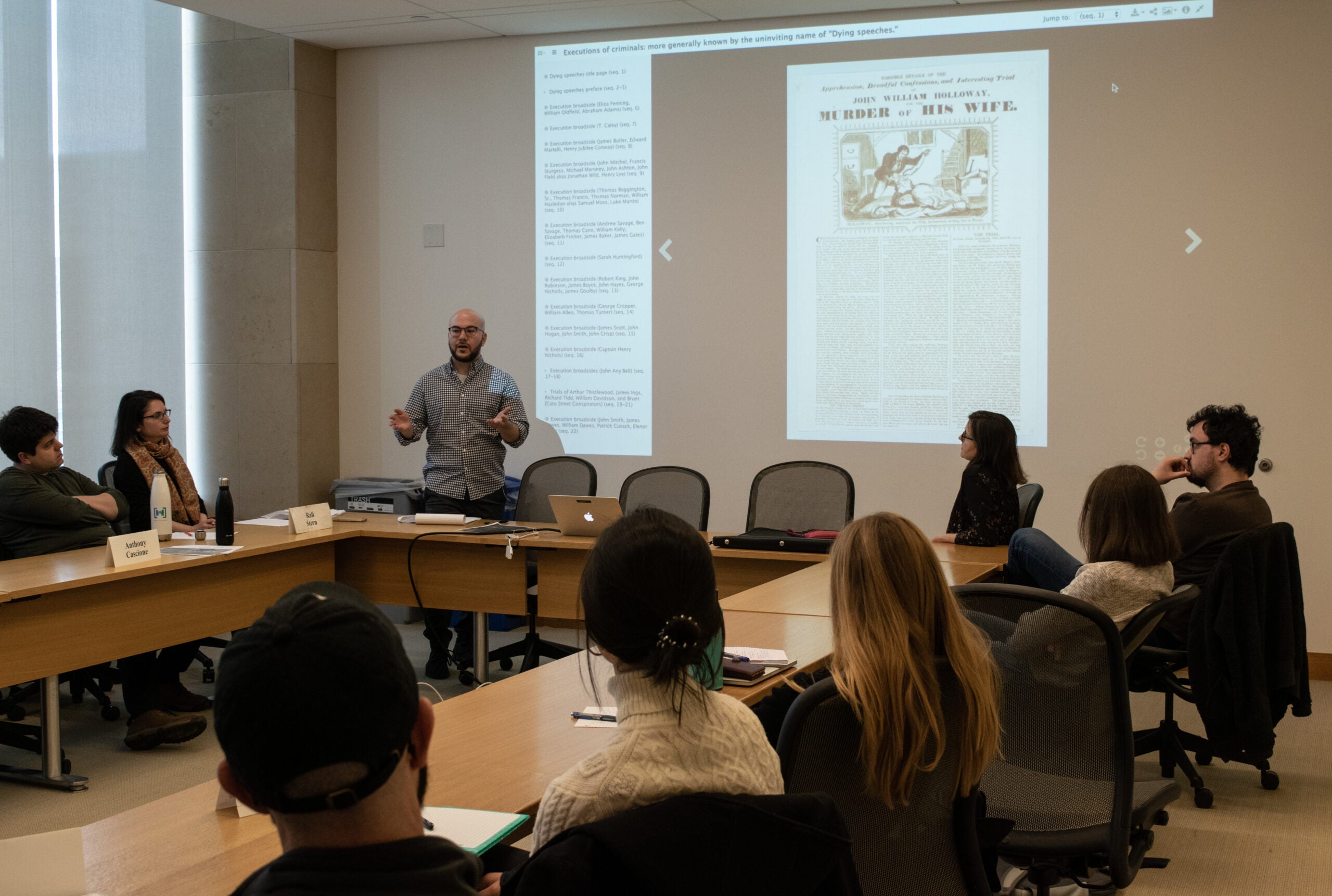

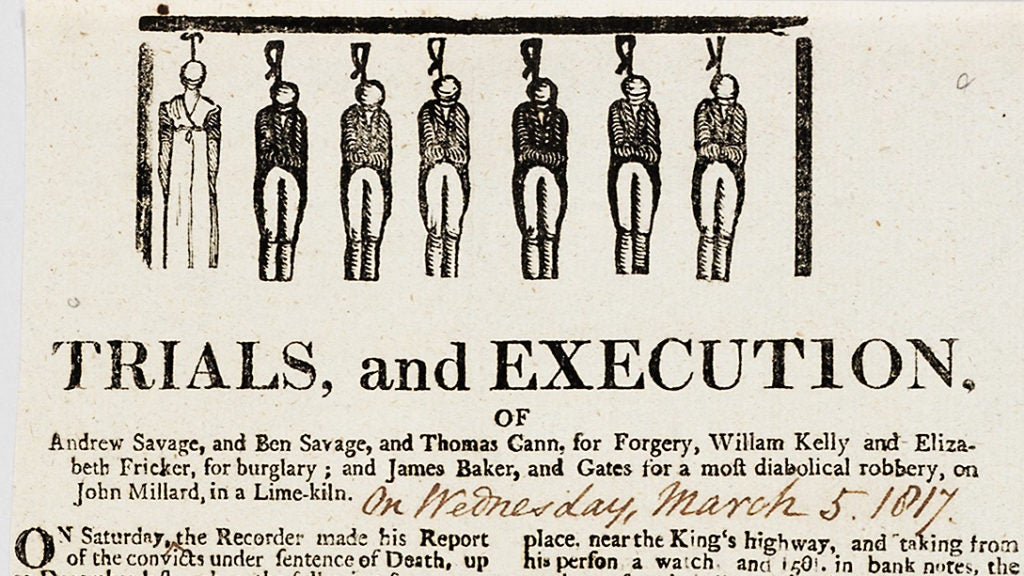

A broadside is a large, single sheet of paper printed on one side. They were published in British towns in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe a crime, typically featuring an illustration (usually of the criminal, the crime scene, or the execution); an account of the crime and the trial; and the purported confessions of the criminal, often cautioning the reader in doggerel verse to avoid the fate awaiting the perpetrator. The publications were intended for the middle or lower classes, and most sold for a penny or less. As part of the class, the students present an analysis of a broadside, including what it conveys about the understanding of the crime and criminal responsibility.

The broadsides “are the most vivid primary source” the students study during the semester, said Kamali. They “permit students to test out the historian’s toolkit: Doing a close reading of the broadside’s text and illustrations, theorizing about the likely audience, and contextualizing the broadside within its broader social and legal context by exploring contemporary evidence of other kinds, such as a transcript of trial proceedings or alternate accounts of the criminal incident, prosecution, or execution.” The Library’s collection of nearly 600 broadsides is one of the largest recorded and the first to be digitized in its entirety. The digitized material spans the years 1707 to 1891 and includes accounts of such crimes as arson, assault, counterfeiting, horse stealing, murder, rape, robbery, and treason.

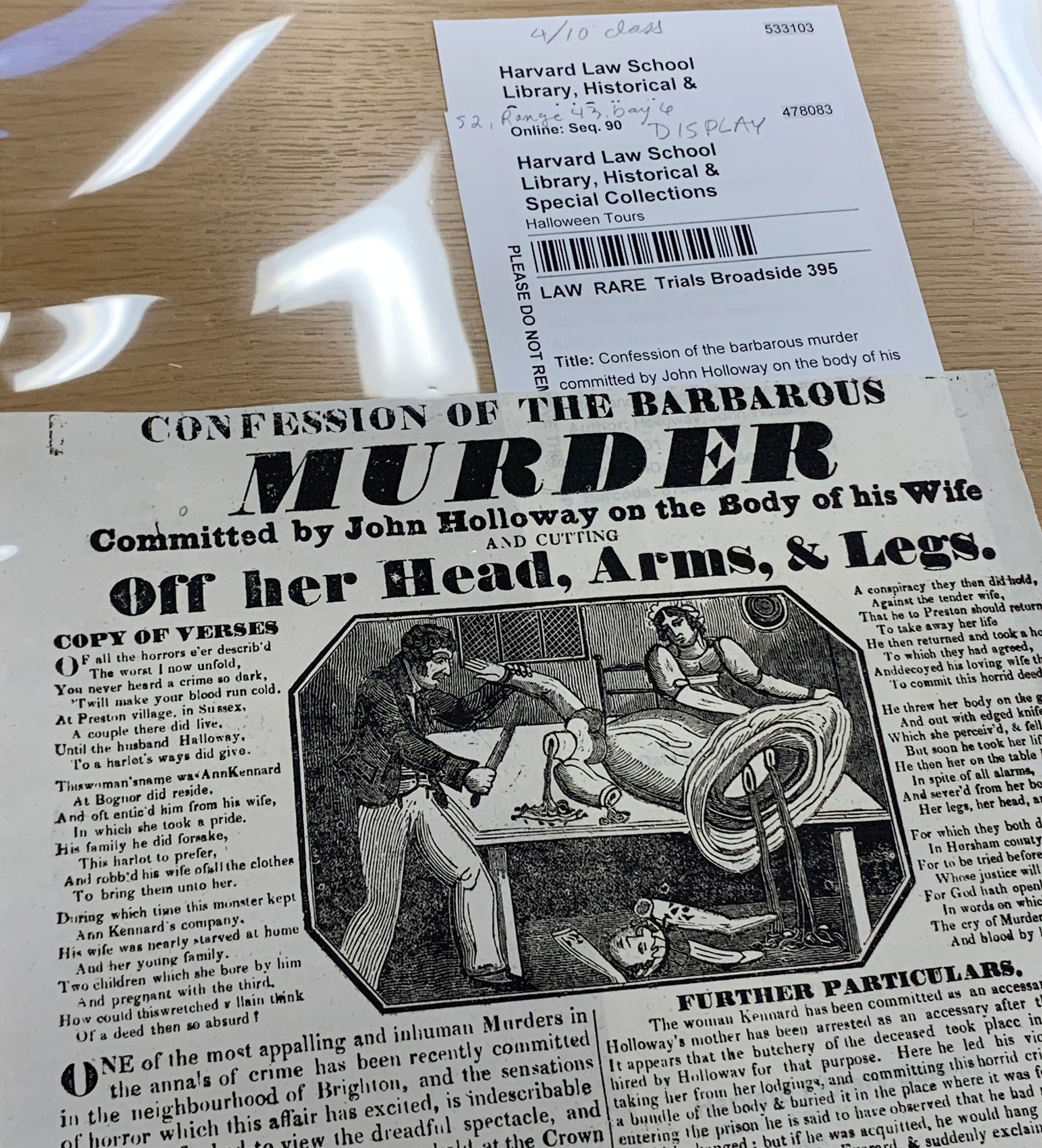

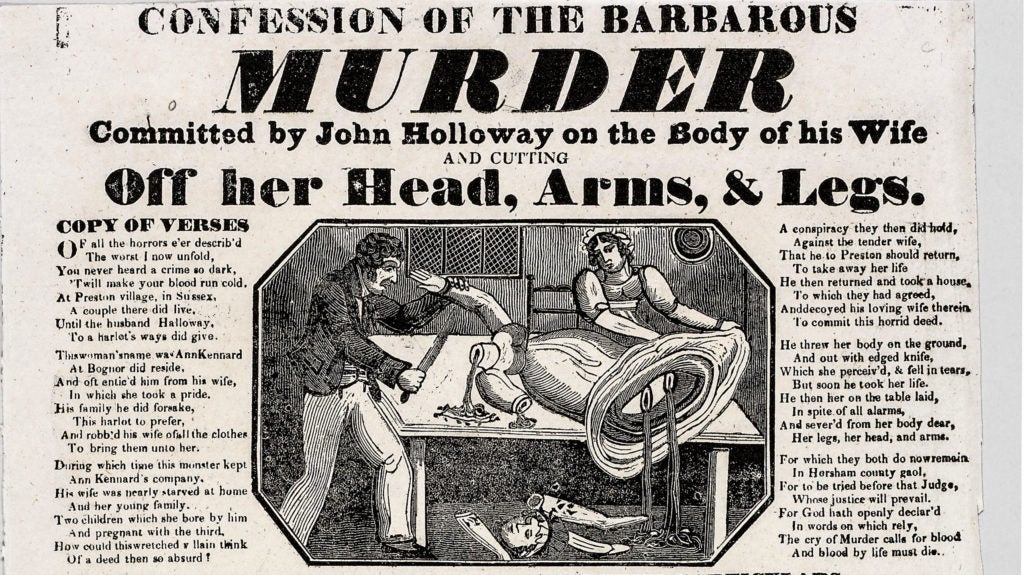

Just as programs are sold at sporting events today, broadsides—single-sheet, frequently sensational publications—were sold to the audiences that gathered to witness public executions in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain. This broadside, titled ‘Confession of the barbarous murder committed by John Holloway on the body of his wife: and cutting off her head, arms, & legs’, depicts the barbarous crime for which John Holloway was executed — murdering and dismembering his wife. (Click on image for full details) Credit: Harvard Law School Historical and Special Collections

Broadsides typically featured an illustration (usually of the criminal, the crime scene, or the execution); an account of the crime and the trial; and the purported confessions of the criminal, often cautioning the reader in doggerel verse to avoid the fate awaiting the perpetrator. (Click on image for full details) Credit: Harvard Law School Historical and Special Collections

A depiction of Fanny Amlett on the day of her execution. She was tried and convicted of drowning her newborn ‘in a fit of Despair, and scarce knowing what she did’ (Click on image for full details) Credit: Harvard Law School Historical and Special Collections

“I’m delighted that Professor Kamali is using the library’s broadsides collection in her class. It’s a great collection because the broadsides can be studied from so many angles: criminal law, sociology, gender relations, printing and publishing history, and even music history,” said Karen Beck, manager of Historical & Special Collections at the Harvard Law School Library.

This assignment offers students a small glimpse of the vast wealth of primary source material in the Library, says Kamali. “I hope that students will be inspired to explore other aspects of the library’s historical collections in writing future research papers.”