What motivates everyday people to do things that are civic?

That’s the subject of some new research by Kate Krontiris, a fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society and the Google Civic Innovation team. Krontiris and two of her fellow researchers, Charlotte Krontiris, and Google UX researcher John Webb, presented an early preview of their findings at a Berkman Center luncheon talk at HLS on March 24. Chris Chapman, also of Google, contributed to the research as a fourth collaborator.

Another way to put the question, Krontiris told the audience, is “How do we engage the unengaged?”

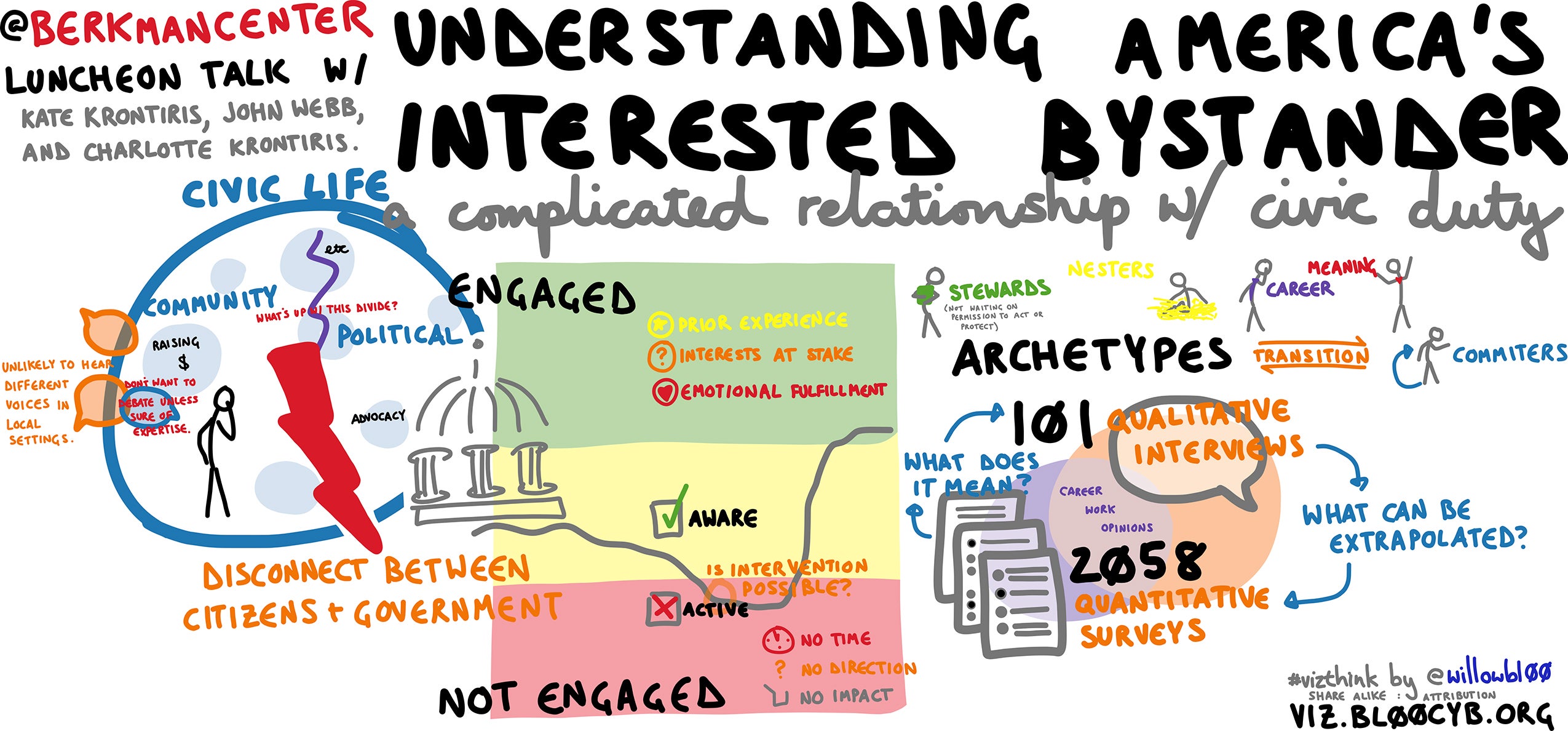

The study, which is not yet published, is intended to inform the design of civic-related products and services at Google and to be of value across the civic technology community more broadly. It involved both quantitative and qualitative research, including 101 in-person interviews and 2,058 digital surveys.

Of particular interest to the researchers were “Interested Bystanders,” people they described as being aware of the world around them but not necessarily taking action or voicing opinions. More than half of the research participants fell into this category.

“Our hope was that if we learn what motivates these people to do things that are ‘civic’—and what holds them back when they do not act—we can better engage this silent majority to be more active participants in civic life,” said Krontiris.

The researchers started with a problem that “too many Americans feel disconnected from public policy and legislative decision-making in the U.S.” From there, they formed two hypotheses: 1) while many people are engaged in their communities as volunteers, most are not participating in the political side of civic life, and 2) to encourage Interested Bystanders to be more involved, we need to understand their unique attitudes and beliefs better.

When asked to name something they had recently done that was civic, Interested Bystanders most commonly cited signing a petition or volunteering, either continuously or at a one-off event. Their main motivation for these actions were prior personal experience or expertise, having clear interests at stake, and seeking emotional fulfillment, according to the research. It became clear that for many people the notion of ‘civic life’ includes community engagement and social relationships.

Our hope was that if we learn what motivates these people to do things that are ‘civic’—and what holds them back when they do not act—we can better engage this silent majority to be more active participants in civic life.

More rare were mentions of things traditionally thought of as civic: protesting or organizing, volunteering for a political campaign, or attending a political event. This points to the idea that Americans’ civic life is often much richer than just those things traditionally associated with being civic, according to the researchers

“This broader civic life taps into their existing experiences and expertise, is more often local, and often gives individuals more power,” said Google’s Webb. “Civic life is more emotionally fulfilling and helps people get over the ‘what’s the point’ hump of inaction.”

Interestingly, when Interested Bystanders did participate in politics, it was in ways they themselves described as less useful and where they felt least powerful. For example, the most common action of signing a petition was perceived by interviewees as not very effective, and many who signed one couldn’t remember what it was for. Many individuals who voted expressed doubt that their vote mattered, but voted out of a sense of duty or routine. Paradoxically, most were voting in national elections rather than local ones, even though many expressed that it was at the local level where they felt they had more power.

The researchers used the quantitative data from more than 2,000 surveys to identify six segments of the American population that span the spectrum from most to least engaged. About half of those surveyed could be considered Interested Bystanders. Krontiris says that this research identifies a valuable snapshot of American life.

How the findings might be used depends on what your goals are, said Krontiris. Individuals and organizations might be inspired to do further research, or to design new approaches for getting people involved in the political process. For Google, it has already informed the design of Election Now Cards, and the collaborators at the company’s Social Impact portfolio have made use of research findings to drive new product ideas as well.

“We know that voting is an incredibly important way that people exercise their power,” said Krontiris, “and what we see is that when people feel involved in their community and describe their civic lives, it’s a whole other set of activities. If what we’re hearing is that civic for them means involvement in the community and doing things with others in socially-oriented ways, then we should pay attention to that.”

For more about the talk, read the live blog from Berkman fellows Erhardt Graeff and Nate Matias on the MIT Center for Civic Media website.