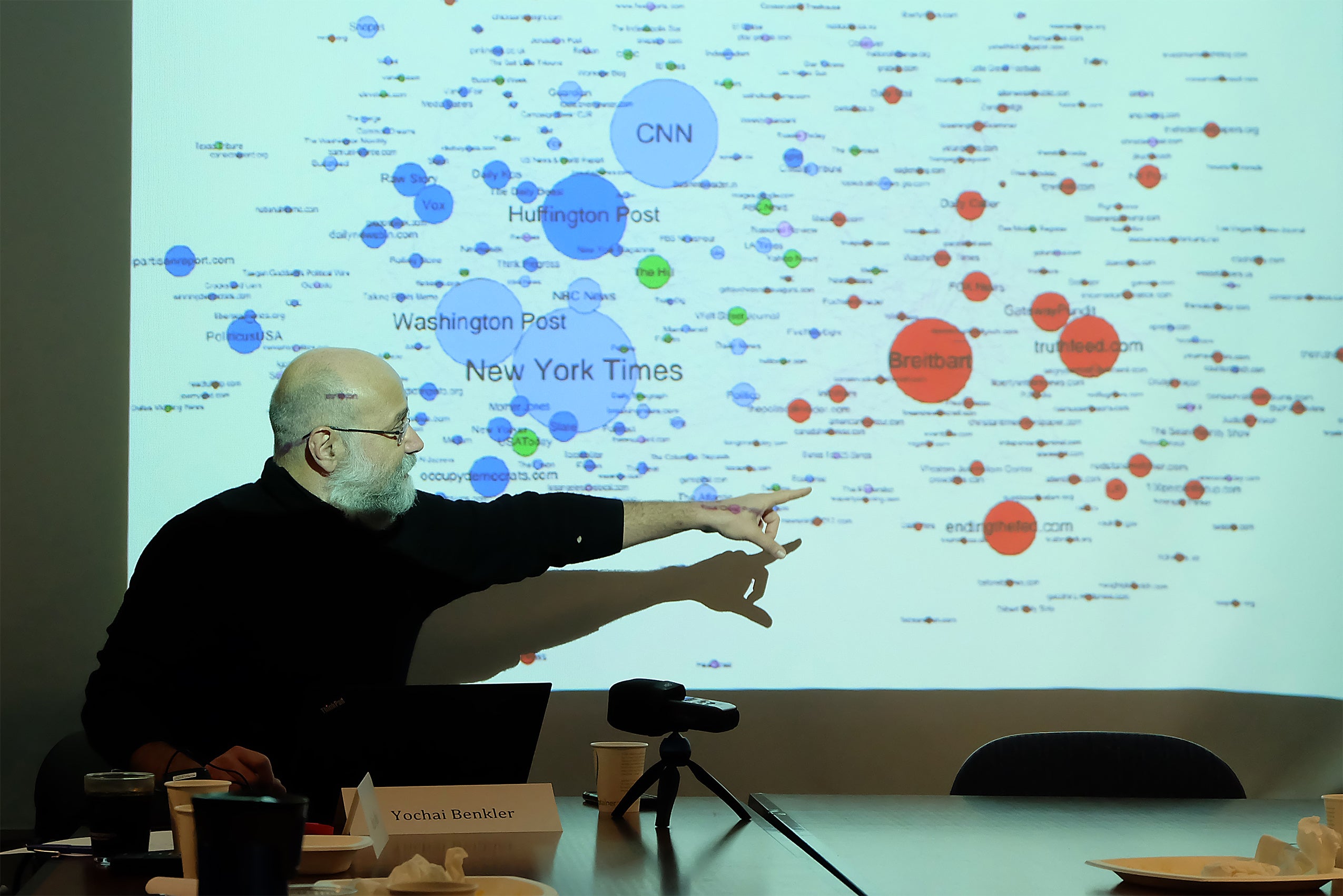

Many arguments have been made about the media’s influence in the last Presidential election. Yochai Benkler ’94, Berkman Professor of Entrepreneurial Legal Studies at Harvard Law School, has undertaken what may be the most scientific study on the topic to date, “Partisanship, Propaganda and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” He studied millions of published stories and social media tweets, what was reported and what was shared. Recently featured on NPR and in the New York Times, the study found a media environment that worked to Donald Trump’s advantage.

This doesn’t mean that the stories themselves were necessarily favorable to Trump; as both he and Hillary Clinton received more unfavorable coverage than favorable. But Benkler’s research shows that Clinton’s coverage was weighted toward unproven scandals, while Trump’s focused on his own preferred issues, particularly immigration. Coupled with the widespread sharing of dubious stories on social media, this slanted the election odds toward Trump.

“The major innovation in this study is that we combine a very large database–over two million stories, millions of tweets,” Benkler says. “We measured from more than one platform, to get a diverse and robust view. And we combined very data-intensive metrics with substantive human coding and qualitative analysis, to give a richer contextualization for the larger scale platforms that come out of the data.”

Conservative websites, most notably Breitbart, were able to rally behind chosen campaign issues, and ultimately behind Trump as a candidate. “Breitbart succeeded in marginalizing the center right and the ‘Never Trump’ camp,” Benkler says. “One of the first critical turning points was when the Breitbart-centered part of the right went strongly after Jeb Bush and then Marco Rubio–and then went after Fox News for not supporting Trump. Fox essentially made the choice to join the bandwagon.”

“One very surprising thing we found was the extent to which the right-wing media ecosystem succeeded in getting its substantive agenda into the campaign. Both candidates got critical coverage but Trump had issues and he had scandals; with Clinton it was only scandals. Looking at Facebook and Twitter, you see that the right wing provided a densely connected and relatively insular network of sites that repeated the same stories and mostly reinforced them. Someone who spent time in that network would come across a storyline: ‘All these sites are saying the same thing, it has to be true’.”

[pull-quote author=”Yochai Benkler” content=”What the study found wasn’t simply a matter of frantic tweets or %SQUOTE%fake news,%SQUOTE% but a successful effort by conservative media to shape mainstream election coverage.” float=”right”]

Though the left wing had dubious sites of its own (the study names Occupy Democrats and Addicting Info among others), there was no such concerted effort, and Clinton supporters were more likely to share less alarmist, if more factual stories. “There were political clickbait sites on the left. But the sites that were usually being shared by Clinton supporters leaned toward the center left—the New York Times, the Washington Post. So what you had was a moderating effect, rather than the amplifying effect that you saw on the right.”

The study goes into detail about one example that proved pivotal in election coverage: The allegations, raised in the Breitbart-endorsed book “Clinton Cash,” that the Clinton Foundation offered quid pro quo favors through State Department policy in exchange for donations (The book specifically charged that the Clintons made a uranium deal with the Russian government. Author Peter Schweizer was credited as a Brietbart senior editor at large; he and Breitbart’s Steve Bannon founded the organization that funded his research).The die was effectively cast when the New York Times ran a April 2015 story, in response to the book, suggestively headlined “Cash Flowed to Clinton Foundation Amid Russian Uranium Deal.”

This Times story was then shared online by a network of conservative sites—Brietbart, Fox News and the Washington Times among them—who began making the Clinton Foundation a buzzword for unspecified corruption. The story was then revived more than a year later, when a film version of Clinton Cash was released in July 2016; this time it had the dual effect of renewing doubts about Clinton and reducing damage to Trump (whose incriminating Access Hollywood interview had been discovered in May). In each case the Times article and particularly its headline were referenced to legitimize the Clinton Cash accusations. It became almost irrelevant that the charges were never proven true. The Times had buried that information (“Whether the donations played any role in the approval of the uranium deal is unknown”) in the tenth paragraph of its story, making it easier for the conservative sites to focus only on the allegations.

Thus the Times (and the Washington Post which ran a later story) were effectively manipulated by Brietbart. “What they did very skillfully was put together a set of materials that could reasonably be framed as raising real questions, giving the Times an exclusive on the data,” Benkler says. “The journalists were tempted into using the evidence and framing it in highly suggestive terms of impropriety, and then burying the fact that there is no actual evidence deep in the story. In the course of this propaganda campaign, the Times and the Post weren’t sufficiently attentive to the degree that they were being played.”

The study doesn’t go deeply into whether Russian collusion helped change the landscape, but it does seem to confirm that American news media were capable of tilting the election on their own. “I wish it were as easy as saying ‘the Russians did it’ or ‘Facebook clickbait did it’. But I think it goes directly back to a longstanding political change with roots in AM radio, with Rush Limbaugh and Alex Jones in the early ’90s. There’s been a longstanding emergence of a gradually more insular and extreme wing in political communications. And I don’t see easy fixes that anybody who holds the First Amendment dear would be happy to sign onto.”

Related coverage

“Down the Breitbart Hole” (The New York Times Magazine online, August 16, 2017)

“Researchers Examine Breitbart’s Influence on Election Information” (NPR’s Morning Edition, March 14, 2017)

A study of 1.25 million media stories says a Breitbart-centered media ecosystem fostered the sharing of stories that were, at their core, misleading. Steve Inskeep talks to researcher Yochai Benkler.

“The great divide: Trump and the press” (CBS Sunday Morning, June 18, 2017)

Senior CBS News contributor Ted Koppel talks with commentator Pat Buchanan and Harvard professor Yochai Benkler about the battle between presidents and the press, what news Americans are choosing to consume, “fake” news, and the media war for hearts and minds.