Is an undocumented immigrant — who nonetheless has strong ties to their community in the United States — one of “the people” whose right to own a firearm is protected under the Second Amendment?

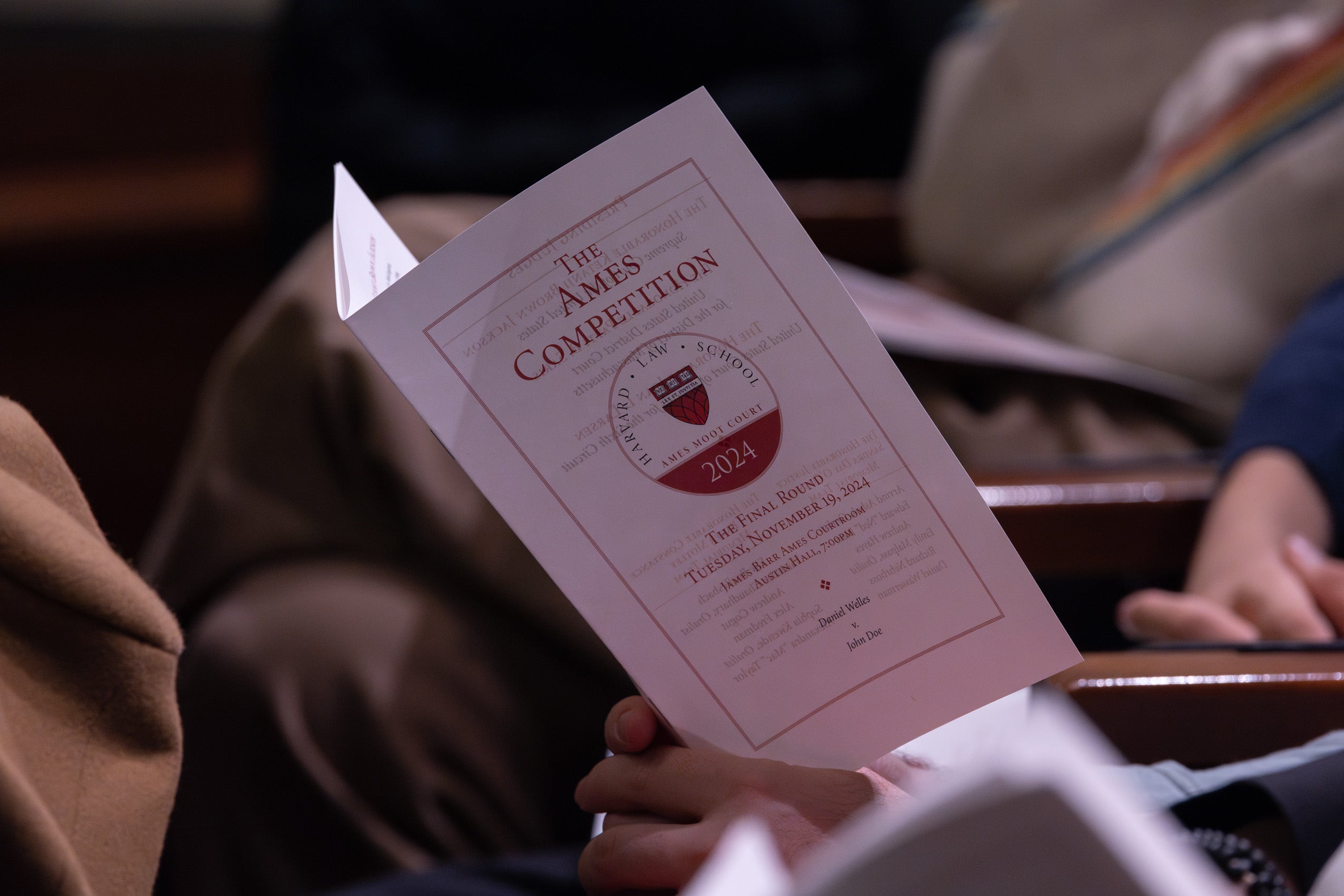

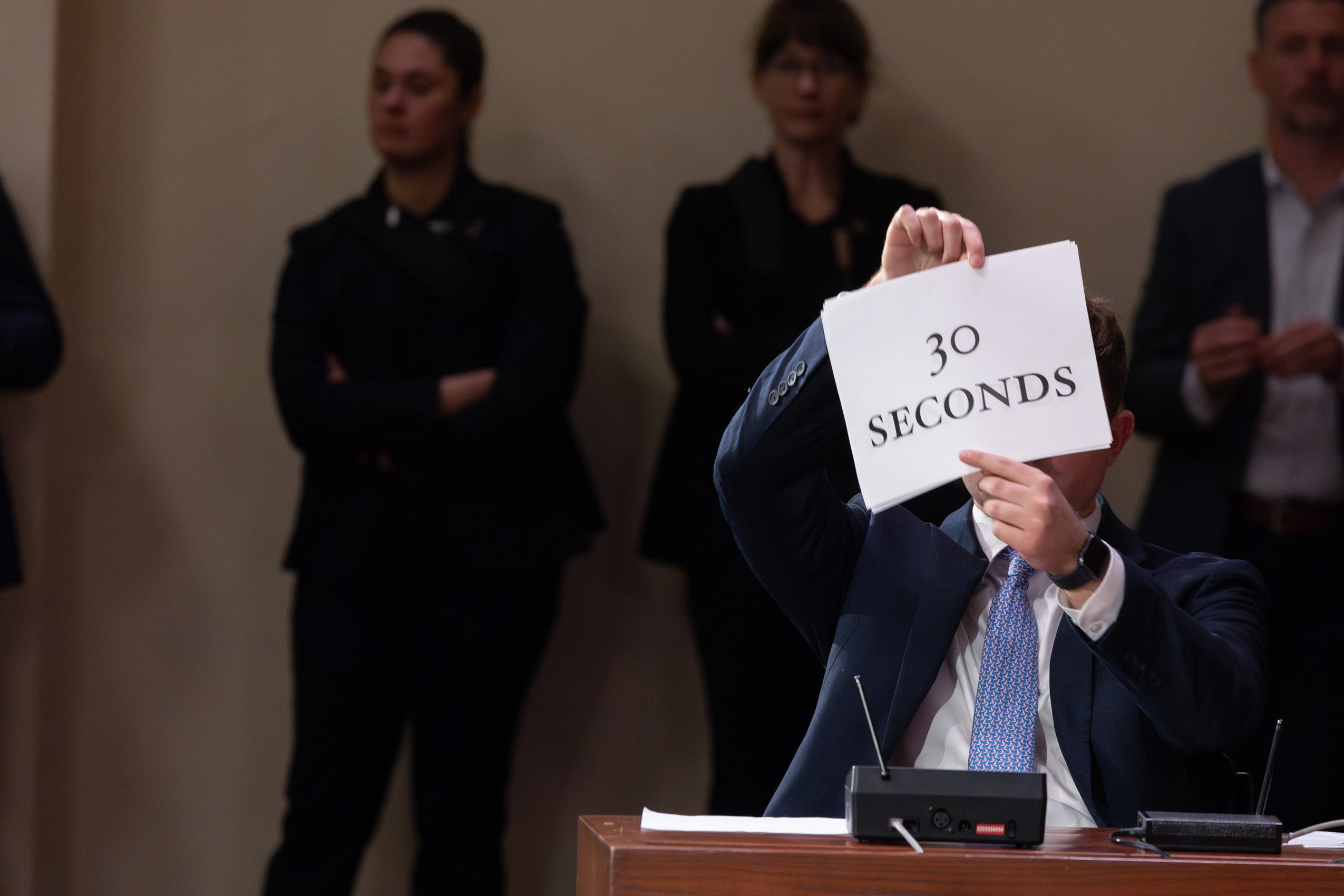

On Nov. 19, two teams of six students squared off on that question during the final round of the 2024 Harvard Law School Ames Moot Court Competition, one of the nation’s most prestigious competitions for appellate brief writing and advocacy.

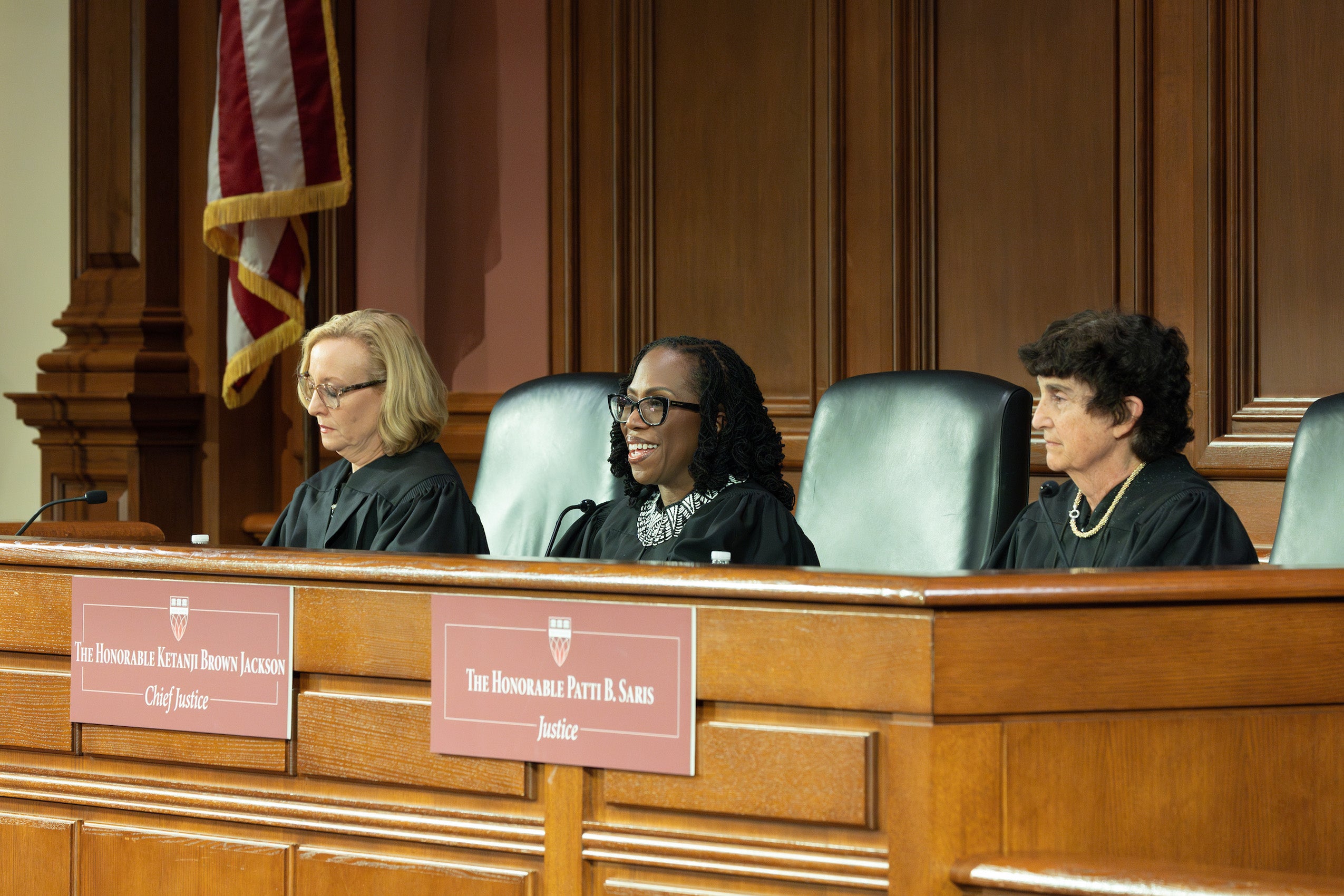

The teams argued before an esteemed panel of judges that included Ketanji Brown Jackson ’96, associate justice of the United States Supreme Court; Patti B. Saris ’76, a former chief judge of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts and lecturer on law at Harvard; and Joan L. Larsen, a circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

At issue was the constitutionality of a real federal statute banning ownership of firearms by undocumented residents of the United States. The fictional case centered on John Doe, an active, upstanding member of his community — who is also present in the country without permission.

Wishing to own a gun for self-defense, the hypothetical Doe sued the government to stop it from enforcing a federal law that bans possession of a firearm by any “alien [who] is illegally or unlawfully in the United States.” Although Doe lost in the district court, the court of appeals reversed that decision, citing a new framework of historical analysis for gun cases required by the Supreme Court in its decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen (2024).

The petitioner’s arguments

The Attorney General of the United States — represented in the contest by the Honorable Justice Sandra Day O’Connor Memorial Team — petitioned the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear its case.

Kicking off arguments for the petitioner was oralist Arvind Ashok ’25. “History, precedent, and common sense show that Mr. Doe is not part of the people. The Constitution does not grant unlawfully present noncitizens the right to bear arms,” Ashok asserted. “History at the founding, and this Court’s precedents, confirm that the original meaning of the term of art ‘the people’ in the Second Amendment referred to citizens only.”

The framers used the terms “the people” and “citizens” synonymously, Ashok continued. “We believe they used the term ‘the people’ when they were discussing rights that were oppositional to the government, and they used the word ‘citizens’ to signify an equality between citizens and each other.”

Questions from the bench came quickly. Justice Jackson wanted Ashok to discuss whether the Court had weighed in on the term “the people” in this context.

Ashok said no. “We don’t believe this Court has ever provided a definitive definition of the term ‘the people.’”

As a result, he continued, it was important to look at historical evidence to determine what the Constitution’s authors believed the term meant. He pointed to a 1787 North Carolina high court case, Bayard v. Singleton, as just one example of where early Americans had used “the people” to mean “citizens.”

But Ashok argued that even if the Court decided to reject the hardline view that noncitizens cannot be part of “the people” — that those with sufficient connections to the country might be included in some way — Doe would still not qualify due to his undocumented status.

There is “some founding era history that suggests that to the extent non-citizens were discretionarily granted access to rights of citizens by states near the time of the founding, those states did so based on the non-citizens’ engagement with the federal naturalization immigration process at the time,” he said.

Ashok’s teammate, Emily Malpass ’25, then discussed the statute’s constitutionality. The law, which “does more to protect Americans from gun violence than any other,” she began, “is consistent with the Second Amendment because it shares a ‘why’ and a ‘how’ with relevantly similar founding era laws.”

As evidence, Malpass described two kinds of firearm regulations that existed at the time of the founding. “First, Congress has broad power to disarm individuals who break the law. Consistent with this longstanding tradition, founding era legislatures disarmed individuals for crimes ranging from assault to fraud to nonviolent peace breaking.”

In addition, the framers were comfortable disarming individuals who had not manifested allegiance to the country, including Loyalists and Confederates, said Malpass.

“So, is it your position that any lawbreaking is sufficient?” wondered Judge Larsen, who added that lower courts have struggled with applying the statute to all felonies — let alone less serious crimes.

“We think it encompasses both individuals who commit felonies and misdemeanors,” Malpass responded. To bolster her argument, she pointed to early laws in states like Massachusetts which intended to disarm people for crimes committed, danger to the public, and even behavior that was “not peaceable.”

“Your brief says we should look back at the British,” interjected Judge Saris. But, she added, the respondents claim that the founders were trying to break from that tradition when they drafted the Second Amendment. What did Malpass make of that argument?

To the extent that the founders were moving away from the pre-ratification tradition, Malpass replied, “they were specifically rejecting the disarmaments that British generals had done to American patriots at the dawn of the Revolutionary War.”

In conclusion, Malpass said, “We’ve refrained from inquiring into the reasons why the founders might have struck the balance that they did. Instead, we simply think, looking at the founding era evidence, there are laws that disarm individuals for nonviolent misdemeanors, Mr. Doe was a nonviolent misdemeanant, and the government would like to disarm him today.”

The respondent rises

According to the Constance Baker Motley Memorial Team, which represented Doe as the respondent, the protections afforded by the Second Amendment are much broader than those advocated by the other side.

Oralist Vaishalee Chaudhary ’25 immediately launched into the heart of her argument. “The Second Amendment is not a citizens-only right. The Attorney General’s citizens-only theory would permanently exclude all noncitizens from ‘the people’ protected by the Bill of Rights and contravenes this Court’s decision in [United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez].”

Doe is an individual with sufficient connections with the nation, Chaudhary continued, and he is therefore part of “the people” as defined by the Court in Verdugo-Urquidez, decided in 1990.

Justice Jackson quickly jumped in, asking Chaudhary her response to one of the petitioner’s arguments — that there is a different frame of understanding for the right to bear arms than other provisions in the Bill of Rights.

“In both [District of Columbia v. Heller] and in [McDonald v. Chicago], this Court found that the Second Amendment is not a second-class right which is subject to a different set of constitutional rules than other amendments,” Chaudhary responded.

Indeed, she later added, “The Attorney General would have this Court find that the framers that were writing the same 10 amendments meant ‘the people’ [to mean something different] in different contexts.”

But have you found another context where an unlawful non-citizen holds a constitutional right, Justice Jackson wondered.

“I don’t think that question has been presented squarely before this Court,” Chaudhary responded, before adding that “in Verdugo-Urquidez, the only case in which this Court has actually analyzed the term ‘the people,’ it had an opportunity to define that as just citizens [and didn’t].”

Justice Jackson also inquired about the implications of the Court’s use of the word “citizen” in the most recent gun rights case, Rahimi v. U.S. (2024).But in Chaudhary’s view, the Court deployed “citizen” merely to describe the litigants in that case — not to outline the universe of all possible rights holders. “The language on ‘law-abiding citizens’ was used to describe those who uncontestably have this right, not to define the entire scope of the right,” she said.

Judge Saris then asked Chaudhary to address a point emanating from the Heller case — whether the term “political community” means something beyond mere physical presence in a country. In other words, is simply living in the U.S. enough of a connection to a “political community” to own a gun, in the respondents’ opinion?

“I think it would still matter whether or not an individual is integrated in the United States society,” she responded. “That gets back to the original meaning of ‘the people.’ For example, we do use a colloquial definition of ‘peoples’ in dictionaries at the time. However, that is indicative of what the framers understood that term to mean …. And that definition was a nation, those who composed a community. It was not one that was based on citizenship. This community-based understanding is what was prevalent at the time.”

Her teammate Sophia Kwende ’25 then addressed the constitutionality of the real federal law barring the fictional Doe from owning a firearm. “This case is about a father seeking to keep a handgun in his house to protect his children due to a rise in home break-ins,” she said. “This Court was clear that the scope of the Second Amendment should be preserved as it existed at the founding.”

The Attorney General’s argument, she argued, would effectively allow the government to use one of the tens of thousands of existing criminal and civil laws to disarm anyone it so chose — “effectively nullifying the Second Amendment.”

So, where would the respondents draw the line, Justice Jackson queried.

To be consistent with Bruen and Rahimi, Kwende responded, “the question would be, what is special about this kind of law breaking? And to do that, we need to look at what was special about the law breaking that allowed the founders, the earlier generations, to disarm people.”

That necessary element, she continued, was violence or the threat of violence. Doe’s offense — illegal entry into the U.S. — “does not include violence,” she noted.

Kwende then went after the historic laws cited by the petitioner as evidence that the founders had intended to allow disarmament of even nonviolent offenders. In reality, she asserted, crimes against “peace-breaking” “involved an element of violence. It wasn’t meant to target nonviolent offenders.”

Judge Saris cut in, wondering what allowing undocumented people to possess guns could mean for the ability of state governments to maintain accurate gun registries. “They’re not going to be able to license or seek licensing for their guns, because that essentially shows that they’re here, and might expose them to be removed from the country, right? So, now you have a very big risk of violence when law enforcement goes in to try and remove them. They are going into households that they don’t know whether the person has a firearm or not.”

Congress may be right to worry about that, Kwende responded, but it can nonetheless only pass laws consistent with the Constitution. As a point of fact, though, she added, Congress had explicitly banned the creation of a federal gun registry. And while many states have their own licensing programs, they could fix the problem by simply creating a pathway for undocumented people to obtain licenses without exposing them to deportation, Kwende said.

Finally, Kwende turned to the petitioner’s argument that the founders had approved of disarmament for those who had not sworn allegiance to the country. Those laws had been passed during times of internal war — the American Revolution and the Civil War — and in many cases, those affected had been allowed to take up arms again after swearing an oath to the U.S., she said.

But Malpass had an answer for this in her brief rebuttal before both sides rested. Many of the Loyalists who had been disarmed were nonviolent — perhaps even good community members — yet they had still lost access to their weapons. “They were butchers, and bakers, and candlestick makers. They went to church. They played on their founding era softball teams. They looked just like Doe.”

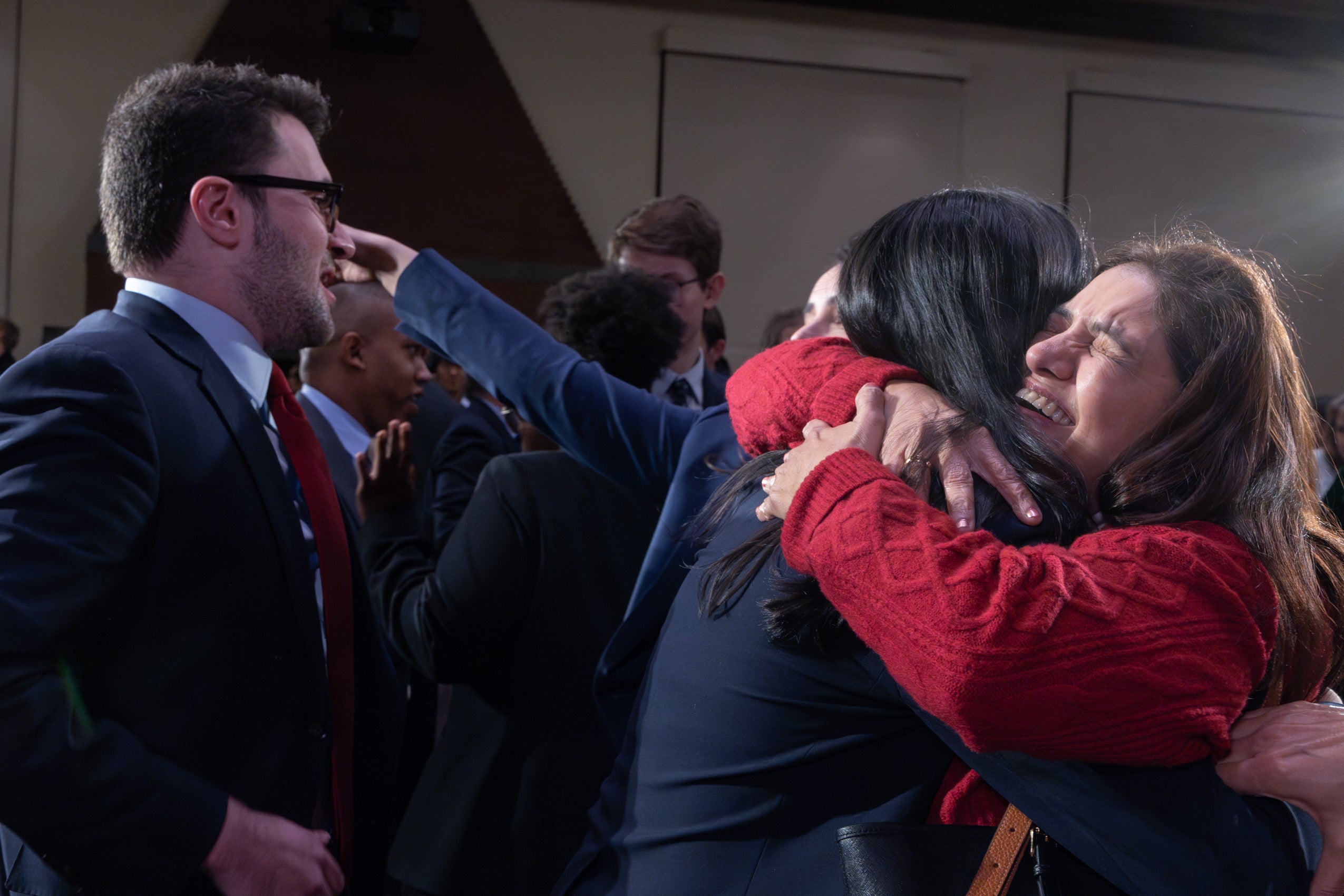

Crowning the winners

Before announcing the winners, Justice Jackson took a moment to acknowledge the hard work of the two teams. “This was an incredibly difficult decision,” she said. “You made it very tough for us.”

Echoing Justice Jackson, Judge Larsen congratulated the participants, noting that they were welcome in her Sixth Circuit courtroom “any time.” “The arguments were just tremendous, super high caliber,” she added.

Larsen then crowned Malpass as Best Oralist.

“It was an honor to argue in front of such an esteemed panel,” says Malpass. “The award is a reflection of the countless hours that all six of us invested in this competition — the oral argument is a product of strong briefing and relentless dedication on the part of the entire team. I’m endlessly grateful for the support of my family, friends, and mentors at HLS.”

With Malpass and Ashok, the Honorable Justice Sandra Day O’Connor Memorial Team included Edward “Ned” Bless ’25, Andrew Hayes ’25, Richard Nehrboss ’25, and Daniel Wasserman ’25.

Judge Saris praised both teams for their excellent advocacy skills — both inside the courtroom and in their written briefs. “Let me tell you all how proud I am to have listened to this advocacy. It was just spectacular. This was such a tough task.”

She then commended the Constance Baker Motley Memorial Team, which had earned the judges’ picks for Best Brief and Best Overall Team.

In addition to Chaudhary and Kwende, the winning team included Andrew Cogut ’25, Elle Buellesbach ’25, Alexandra (Mac) Taylor ’25, and Alex Fredman ’25.

In a statement, the group told Harvard Law Today that it had been a highlight of their law school careers to participate in the competition and to continue the storied Ames tradition.

“It was an incredible honor to see our hard work pay off before Justice Jackson and Judges Saris and Larsen last night,” they added.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.