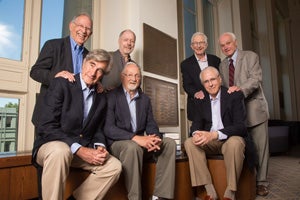

On a sunny day in June, seven members of the Sacks club, the team that won the Ames moot court competition in 1959, met on the steps of Langdell library to reminisce over what they called their “unlikely” victory, and to talk about where their lives had taken them in the fifty years since.

The reunion was occasioned by a box that Joseph Steinberg, one of the two main oralists for the team, had dug up in his basement—filled with a collection of printed briefs from the Sacks club and their opponents in all three rounds of the competition and copies of the posters that had been put up around campus to advertise the highly anticipated event. Steinberg contacted David Warrington, until this past summer the head of archives and special collections at the law library, who was eager to add the collection to the law school’s archives. Then Steinberg contacted his former teammates—Ansel Chaplin, John Demmler, Geoffrey Gowen, Richard Hobson, John C. Keene, Gordon Millspaugh, Jr. and Walter Noel, Jr.—to ask them to dig through their own collections. Slowly, the idea for holding a reunion was hatched by Steinberg and Chaplin.

Joseph LeVow Steinberg, Geoffrey H. Gowen and Richard R. G. Hobson

Joining the Sacks club on the steps were Warrington and Milton Bordwin ‘55, the author of the case, whom the group had tracked down to invite to the reunion. Bordwin invented a case in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ames Circuit where a citizen accused a local radio and television station of defamation—“this devilish case we spent so much time on,” as Steinberg called it. As Bordwin stood flipping through the 43-page brief for the appellee that Steinberg had brought with him he said, “This is a good case; I enjoyed this. But it was a lot of sweat, a lot of hard work.”

The group headed inside and upstairs into the main reading room of the library, where they paused by the bronze plaque where their names were inscribed, alongside plaques listing the best oralists of all the other moot court contests, among them Henry Friendly ’27, Harry Blackmun ’32, Cass Sunstein ’77, and Deval Patrick ’81.

They then headed up to the Special Collections room, where memorabilia related to the group and their case was laid out on a table, including a picture of them from the 1959 yearbook and a handwritten postcard from Professor Albert Sacks, the faculty leader of their club, asking to move a meeting from campus to his home in Belmont. Standing around the table, the men recalled how they had seen themselves as underdogs, partly because the team they competed against in the finals, the Holmes Club, had some star students among them. “I think it’s fair to say that there was no one who was academically outstanding in our group,” remembered Geoffrey Gowen.

But they worked hard and they worked well together; and their captain, John Demmler, made a strategic decision that may have been the key to their victory. While he had presented the oral arguments with Chaplin in the first round; Demmler suggested that Steinberg take over for him in the semi-finals and finals, leaving himself more time to oversee the researching and writing of the briefs.

Their case was heard by three judges, including Harold Burton 1912, who had retired from the Supreme Court the year before. The Sacks club won the case on a 2-1 vote, and the strength of their brief was cited as the decisive factor. “We eventually won the argument, as I understood it, on the basis that Mr. Justice Burton thought we had written a distinctly better brief,” said Chaplin. Steinberg saw their victory based, too, on the camaraderie they shared. “We won because we really worked well together and we liked each other, and I think that showed up in our work.”

Walter M. Noel, Jr., Gordon A. Millspaugh, Jr. and Richard R. G. Hobson

The group continued their reminiscences over lunch at the Faculty Club, with the talk turning to funny stories about their moot court experience. Chaplin recalled that after his and Steinberg’s victorious oral argument in an earlier round of the competition, he fished for a compliment from Professor Benjamin Kaplan, who had been in the audience. “Kaplan told me: ‘I think you did pretty well—your argument was particularly turgid.’ I said thank you then went home and looked it up and was mortified!”

Steinberg, the one who had organized the event that brought them together, gave a toast that summed up why so many of their group had made the trip to Cambridge to commemorate something that had happened long ago. “This is a once in a lifetime opportunity for a bunch of old friends to get together and remember what was a very important signature accomplishment of our young lives way back then.”