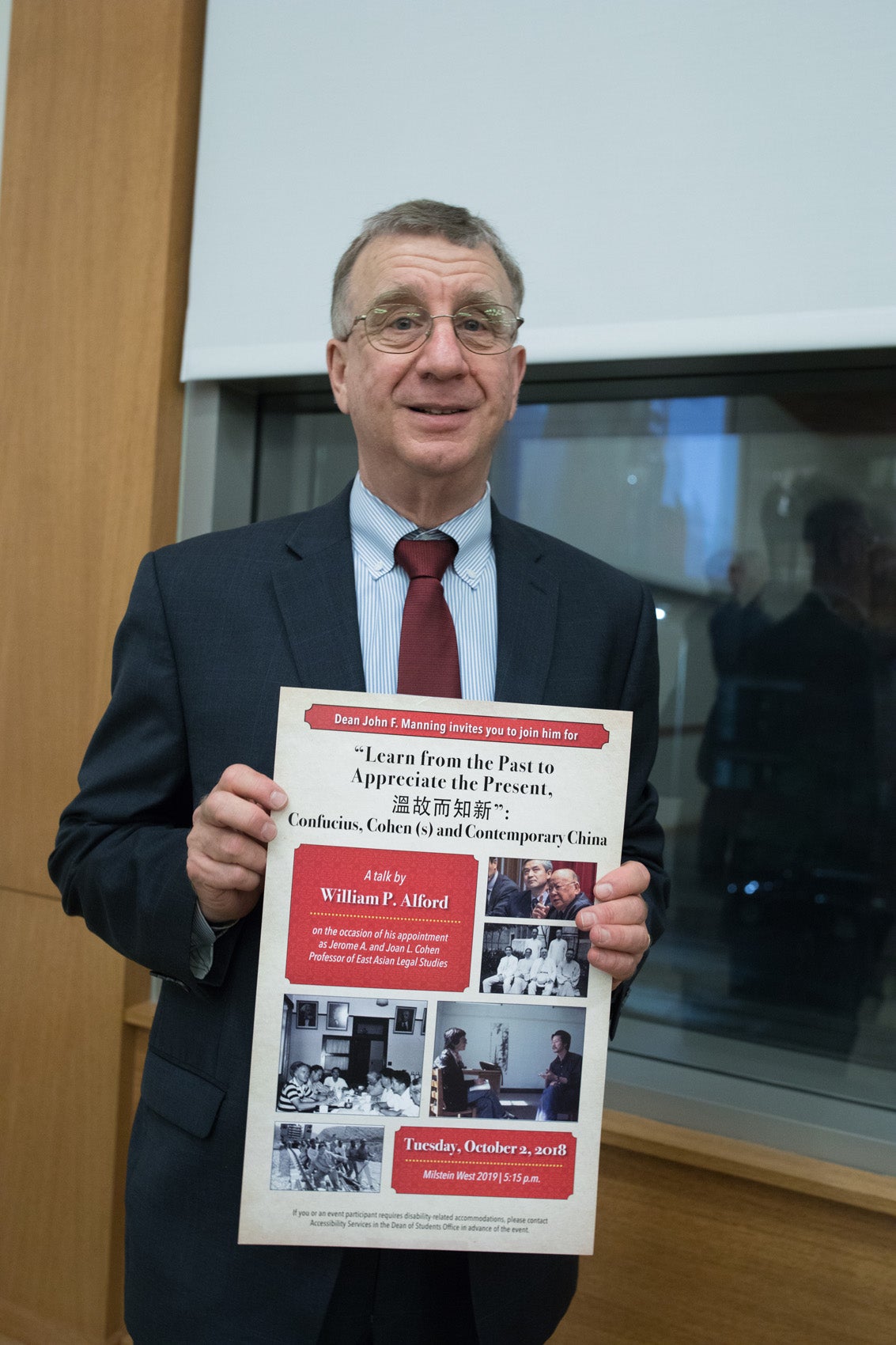

Harvard Law School Professor William Alford ’77 was a participant and panelist at major events on the political and legal future of China, held recently at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., the Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia, and the Fairbank Center at Harvard.

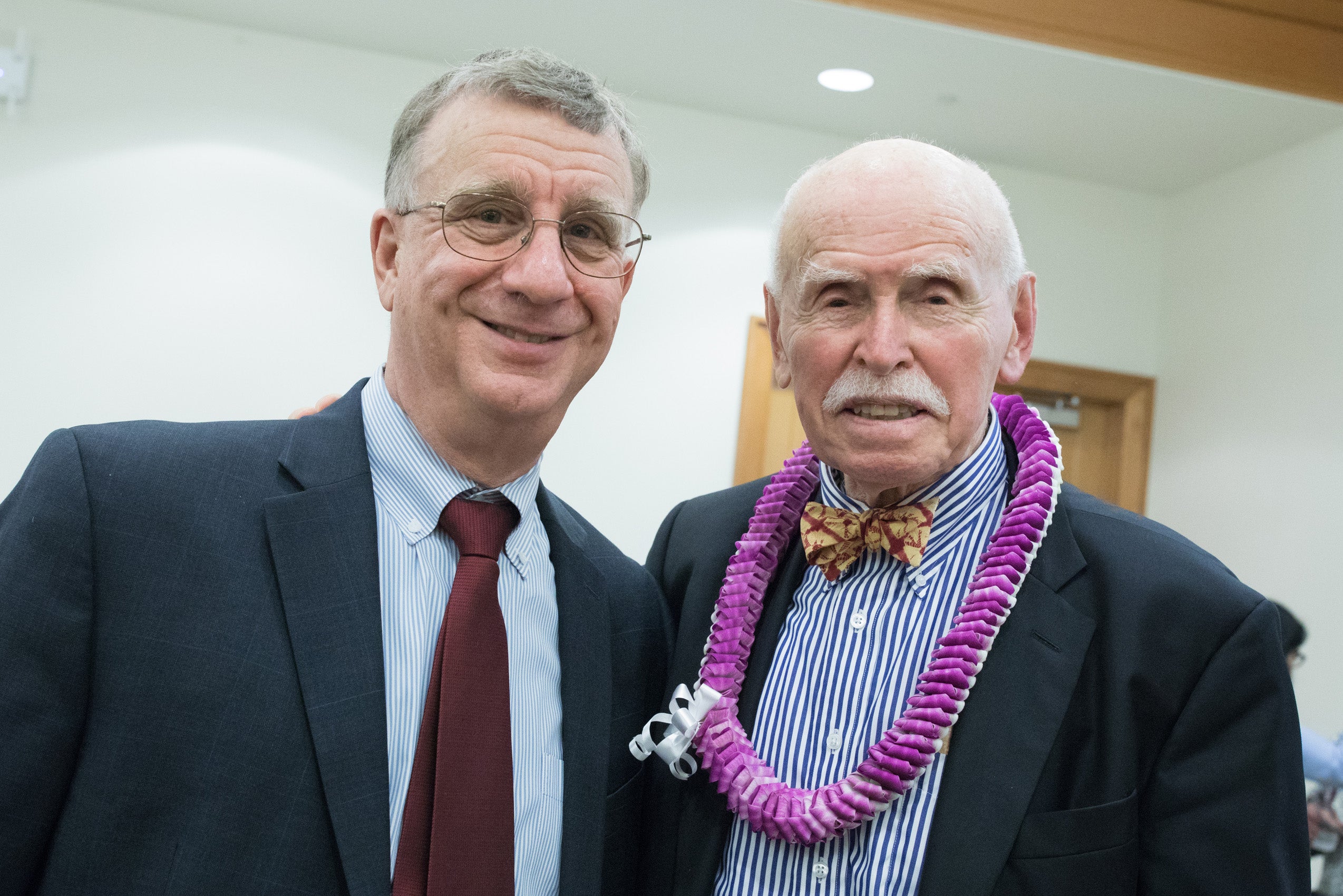

On Nov. 28, Alford spoke on a panel titled “Rule of Law in China: Prospects and Challenges” at the Brookings Institution along with Jerome Cohen, professor at New York University School of Law, and Paul Gewirtz, professor at Yale Law School. Jon Huntsman, former U.S. ambassador to China, moderated.

Watch video of the panel on C-SPAN.org

The panel was part of a celebration to launch “In the Name of Justice: Striving for the Rule of Law in China,” the new book by He Weifang, an outspoken and well-known legal scholar at the Beijing University Law School who first came to study in the U.S. as a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School in the 1990s. Also speaking at the event were U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer ’62; John Thornton, chairman of the board of Brookings; Martin Indyk, vice president and director of foreign policy at Brookings; and Cheng Li, Brookings senior fellow.

An expert on Chinese law and legal history, Alford engaged Professor He’s work in four respects. The first was to argue for greater attention to resources to be found in China’s past as it looks to implement reform—from Confucian ideas about constraints on power to specific procedural protections in 18th and 19th century Chinese law. Beyond what these offer conceptually, “it is hard to imagine the rule of law taking hold in China,” said Alford, if it is seen solely as an import. Second, Alford suggested that too often those looking for a model to help reform Chinese laws have focused on the U.S. to the exclusion of other countries. Greater consideration of the array of “institutional designs” through which different nations realize “universal ideals that promote human dignity” might offer more possibilities for China to fashion its own measures that advance those ideals, he said.

Third, Alford called for further focus on the ways in which ordinary Chinese citizens are now seeking to hold their government to its promises, invoking the law as they endeavor to protect their rights and interests, including against abusive officials. And, fourth, he spoke to the relationship between legal reform and politics in China. “Too many scholars, both Chinese and foreign, have acted as if legal reform will be the driving force for political reform,” he said. But the experiences of other jurisdictions, such as Korea and Taiwan, he added, suggest that the difficult challenges political reform present cannot be avoided.

In October, Alford participated on a panel titled “What’s Next for China?” at the Carter Center in Atlanta, Ga., along with Joseph Fewsmith, professor of international relations and political science at Boston University, and Yawei Lui, Carter Center vice president for peace programs. And on Nov. 30, Alford delivered a talk titled “How Law Doesn’t and Does Matter” at a major international conference, Chinese Politics Past and Present: The 18th Party Congress, held to mark the retirement of Roderick MacFarquhar, Leroy Williams Professor of History and Government at Harvard.

Alford is the Henry L. Stimson Professor at Harvard Law School. His most recent publication (co-edited with William Kirby and Kenneth Winston) is “Prospects for the Professions in China” (Routledge, 2011). In the early 1980s, he founded the first academic program on U.S. law in the history of the People’s Republic of China. In 2007, in his role as chair of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, with Dr. Michael Stein ’88, he organized the People’s Republic of China’s first conference on disability law, in conjunction with Renmin University of China and the China Disabled Persons’ Federation.