Imagine telling the story of a yearlong trial of Nazi leaders through an immersive documentary that uses only archival material for the visuals and has no narrator. That was the task that Andrew Eastel, the creative director at Middlechild Productions, helped to take on as the producer behind a documentary film about one of the most famous murder trials in history.

The film, “The World’s Biggest Murder Trial: Nuremberg,” directed by filmmaker Jenny Ash, depicts the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, the first and best-known of the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials. Held from 1945 to 1946, it involved a multinational team of prosecutors who indicted 24 Nazi leaders and ultimately helped shape the international legal landscape. In the few years that followed, American prosecutors held an additional 12 trials in the same German city against defendants from different sectors of Nazi German society, including judicial, military, and medical workers.

Telling the story of the first trial through a documentary involved grappling with various records from a lengthy event that happened 75 years ago. Fortunately for the filmmakers, they were able to get a digitized transcript of the entire first trial from the Harvard Law School Library’s Nuremberg Trials Project. Although audio recordings and filmed portions of the trial also exist, the transcript was the one thing they could easily obtain that had the whole trial in it, Eastel said.

The team was able to use the transcript to find out when things happened, or work out which parts of the trial were filmed and which parts they could seek out audio for. “It wouldn’t really have been possible, necessarily, for us to have told the story in as much depth as we have without having it as a reference point,” said Eastel.

The film, which premiered on British television’s Channel 5 on December 1, is one of many projects that have drawn on the vast collection of Nuremberg documents held by the HLS Nuremberg Trials Project. “It’s incredible documentation of one of the most important events of the 20th Century—World War II and the atrocities committed during that war,” said Ed Moloy, who is curator of modern manuscripts at the Harvard Law School Library.

The transcript sent to Eastel is part of around a million pages of Nuremberg documents in the library’s archives. The project has been working for many years to digitize the documents and increase accessibility, and is slated to finish putting all the English-language versions, plus a number of the original German-language documents, online in about a year. That will make the project the only digitally available, comprehensive set of Nuremberg documents in the world, according to Paul Deschner, the project’s manager and technical lead.

Eastel said there are a lot of similarities between the history examined at the International Military Tribunal and things that have happened since or are still happening today. And that connection won’t be lost on viewers of the documentary, which was commissioned in the U.K. and will be sold to different countries over time. “At the end of the film, we cover some parallels with certain modern-day events and individuals that actually bear shocking similarities,” he said.

A Graphic Novelist

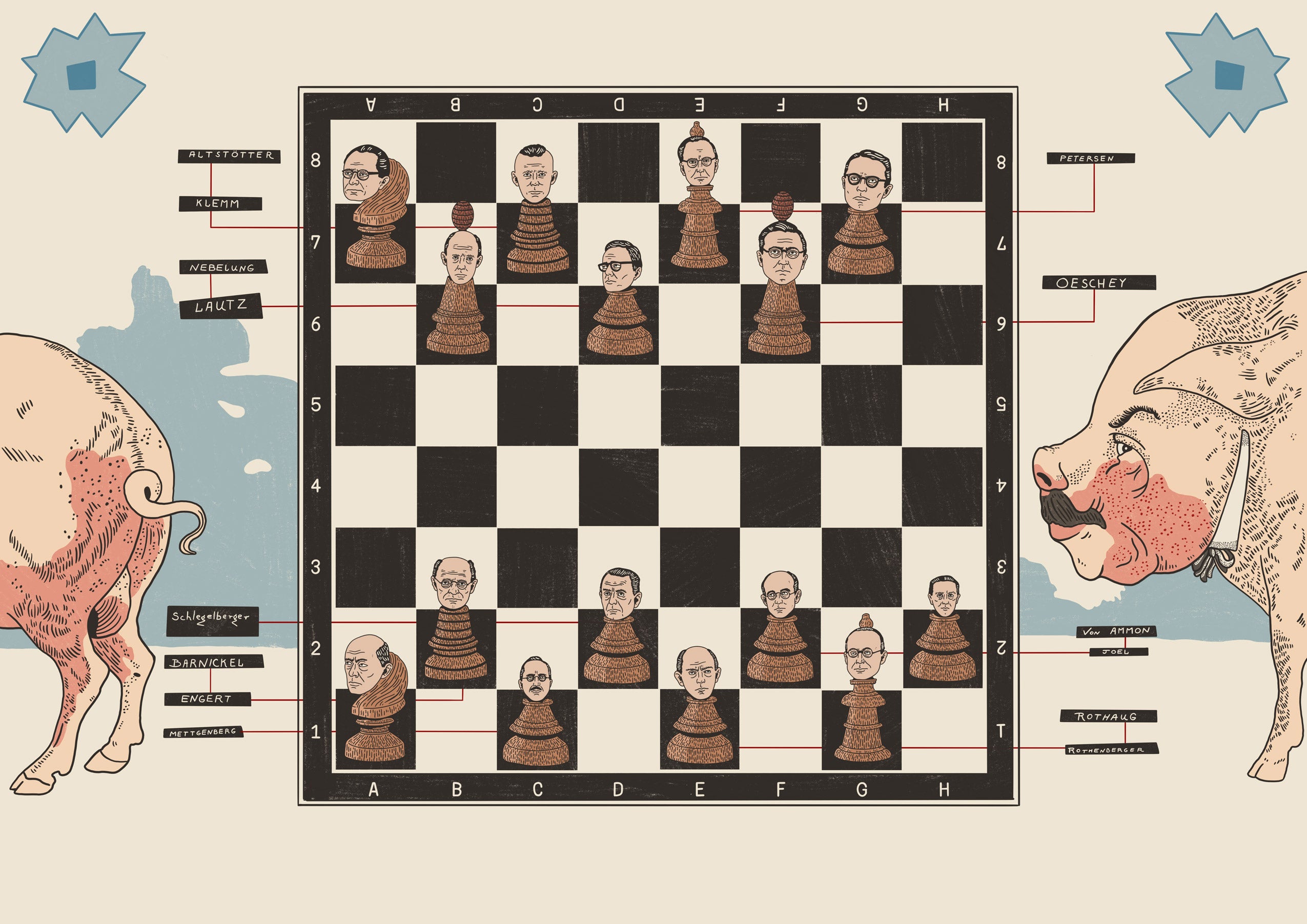

Hannah Brinkmann, a graphic novelist from Germany, has also seen connections between the Nazi history that was on trial at Nuremberg and the post-war events that followed—in her case, looking at German history in particular. She is using documents from the HLS digital project as she works on a graphic novel about the third American-led trial, in which leaders within the Nazi-era justice system were prosecuted. She hopes to explore not just the trial of those individuals, but also how the post-World War II German judicial system was affected by the ongoing participation of judges from the Nazi era.

Looking at the real documents helps Brinkmann to get ideas for drawings and ways to build a page in a graphic novel. In her last graphic novel, a work in German whose title translates to “Against My Conscience,” she also drew on documents from the Harvard Law Library, where she was a Library Innovation Lab Fellow in 2018. That story examined how the West German judicial system treated men in the 1970s who claimed they were conscientious objectors who should therefore be able to avoid mandatory military service under the law.

It was a story that actually helped inspire Brinkmann’s current project. The 1970s system forced objectors to go before a committee composed of a judge and two assessors from the defense ministry to try to prove that their conscientious objections were genuine. At this proceeding, a man might be asked what he would do if he were attacked or his girlfriend were raped, Brinkmann said. If the man said he would attack back or try to save his girlfriend, the committee would say he wasn’t a conscientious objector. If he said he would do nothing, the committee would say it didn’t believe him.

If that committee didn’t believe the objector, he could go before a second one, and if the second also didn’t believe him, he would be drafted into the military before he was able to have a third proceeding—one that, unlike the first two, was usually before a real court of law. Many had to serve much or all of their time before that third proceeding, Brinkmann said.

The story was personal for Brinkmann. Her uncle was denied status as a conscientious objector in his first two proceedings in the 1970s and was conscripted into the military before his third one. A few months later, he took his own life. His death led to discussion within Germany about changing the system. “It was obviously a remnant of this very weird way of thinking about systems and freedom and government,” Brinkmann said.

The foreign prosecution of Nazi-era judges at Nuremberg shows, for Brinkmann, what could have been, if Germany had held its own judges accountable. “We don’t really like to talk about it, because it was already the ‘new Germany’—but then it really wasn’t,” she said. “I think it’s just important to focus on that again and again.”

Academic Researchers

The Nuremberg Trials documents have also provided fertile ground for academic research. Brandon Bloch, a historian at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, described the documents as “the most important archive not only of 20th century international criminal law, but really the crucial archive of the Third Reich and the Holocaust.” Bloch has used the Nuremberg Trials Project as a resource to help his students do their own research in two different courses, one focused on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust and the other looking at the history of 20th century international law and war crimes tribunals.

That student research has covered an array of topics. One student this semester, for instance, is examining how the Nuremberg trial of 23 doctors and administrators, who were alleged to have been complicit in crimes such as medical experimentation and forced sterilization, sheds light on Nazi racial ideology.

Another student is looking into medical experiments conducted on Roma people in particular. (The Roma are an ethnic group that lives primarily in Europe.) “He’s discovered through these documents that, even though the atrocities and genocide against the Roma were largely forgotten until their community started to receive reparations in the 1990s and 2000s, as early as the medical trial in 1946, there was already evidence brought to light of these atrocities,” Bloch said.

Student Researchers

For Meaghan Kacmarcik, an undergraduate history major at George Washington University who took a course on the Holocaust, document digitization by the Nuremberg Trials Project was especially helpful. Many of her fellow students turned to archives at the U.S. Holocaust Museum to ground their research papers, but a lot of those original materials weren’t digitized and couldn’t be magnified. As a student with a visual impairment, Kacmarcik couldn’t read those documents, but she was able to go through digitized documents from the Nuremberg Trials Project, and also convert them into audio using an app, which let her more easily take notes and read faster.

Kacmarcik’s paper, which she later presented at a history conference, looked at the Nazi forced labor program and racial ideologies through the lens of language used by party officials to describe forced laborers from Poland and Eastern Europe. She analyzed, for instance, German official Otto Bräutigam stating: “With a presumption unequalled we put aside all political knowledge and to the glad surprise of all the colored world treat the peoples of the occupied Eastern territories as whites of Class 2, who apparently have only the task of serving as slaves for Germany and Europe.”

“To draw parallels between historic practices of slavery and ultimately renew such horrific patterns with a new population of people is an indicator of how deep the disdain and hatred for Eastern Europeans runs in the upper echelons of the Nazi party,” Kacmarcik wrote of Bräutigam’s language.

Generous supporters have made all this happen, Deschner said, but it’s a lengthy and expensive enterprise. With continued support, the Nuremberg Trials Project hopes to pursue a larger effort to provide scholarly information related to all the digitized trial-exhibit documents it puts online. It also aims to offer full-text search for all the documents, which it has already done for some of the trial transcripts. Full-text search would allow researchers the flexibility to search for particular words or phrases across all the documents.

A documentary, a graphic novel, and student research—these are just a few examples of the work the HLS Nuremberg Trials Project has already supported. And with a goal of getting all the English-language documents online in a year, and deepening the entire offering in the years that follow, there’s reason to expect even more creative work and research to come.