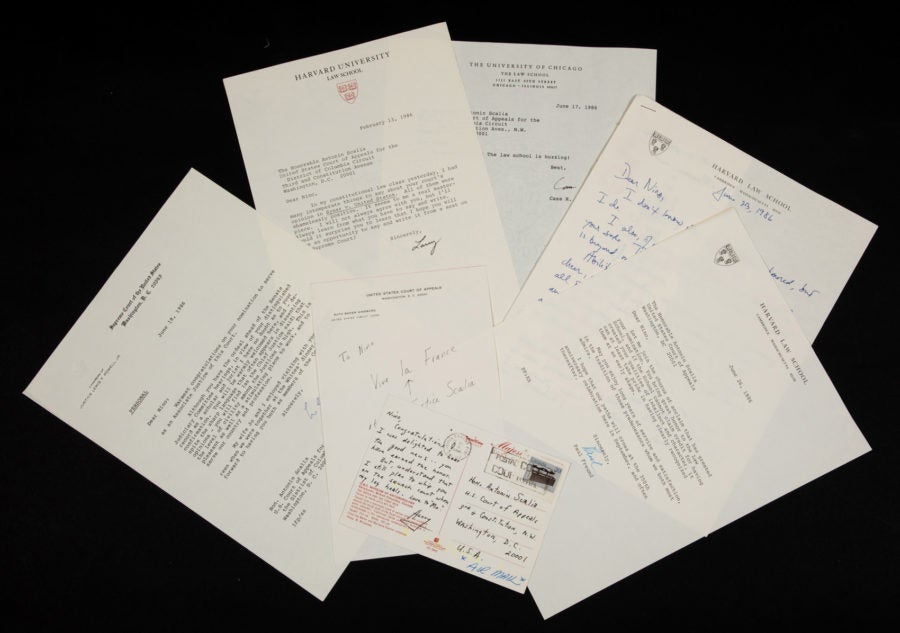

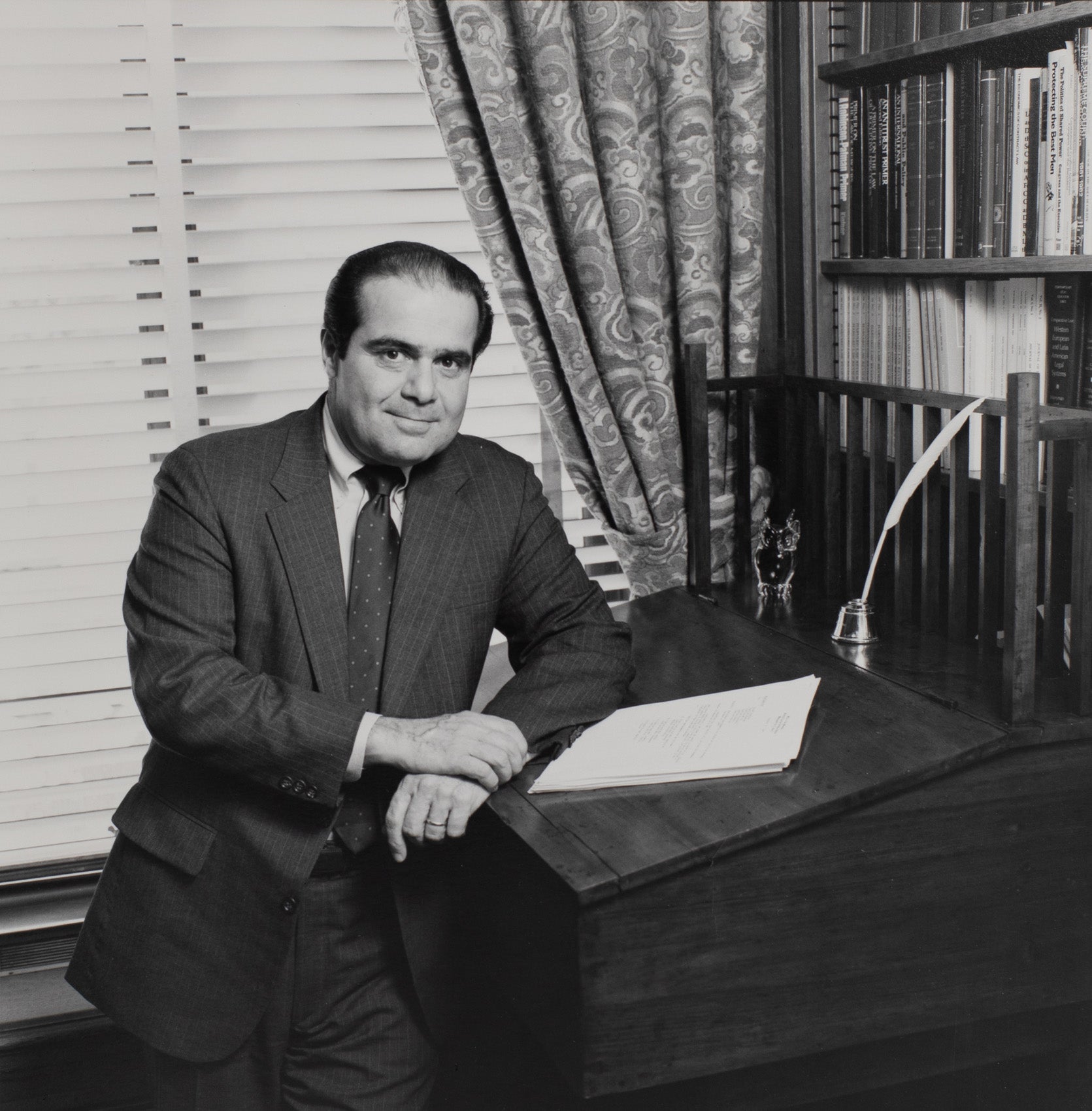

The public release this month of the first set of materials from the Antonin Scalia Collection was a pivotal moment for curators and archivists at the Harvard Law School Library. For nearly three years, they have been working to catalogue the massive trove of personal correspondence, photographs and court files, among other items, from the late United States Supreme Court Justice’s files. Donated to HLS by his family in 2017, the collection consists of about 400 linear feet of records, which will be made available to researchers in stages over the course of the next 40 years.

Harvard Law Today recently sat down with Ed Moloy, the library’s curator of modern manuscripts, and Project Archivist Irene Gates to discuss the Antonin Scalia Collection, the work of archiving, preserving, and making it public, and other collections held by the Harvard Law Library.

Harvard Law Today: Can you briefly describe the collection?

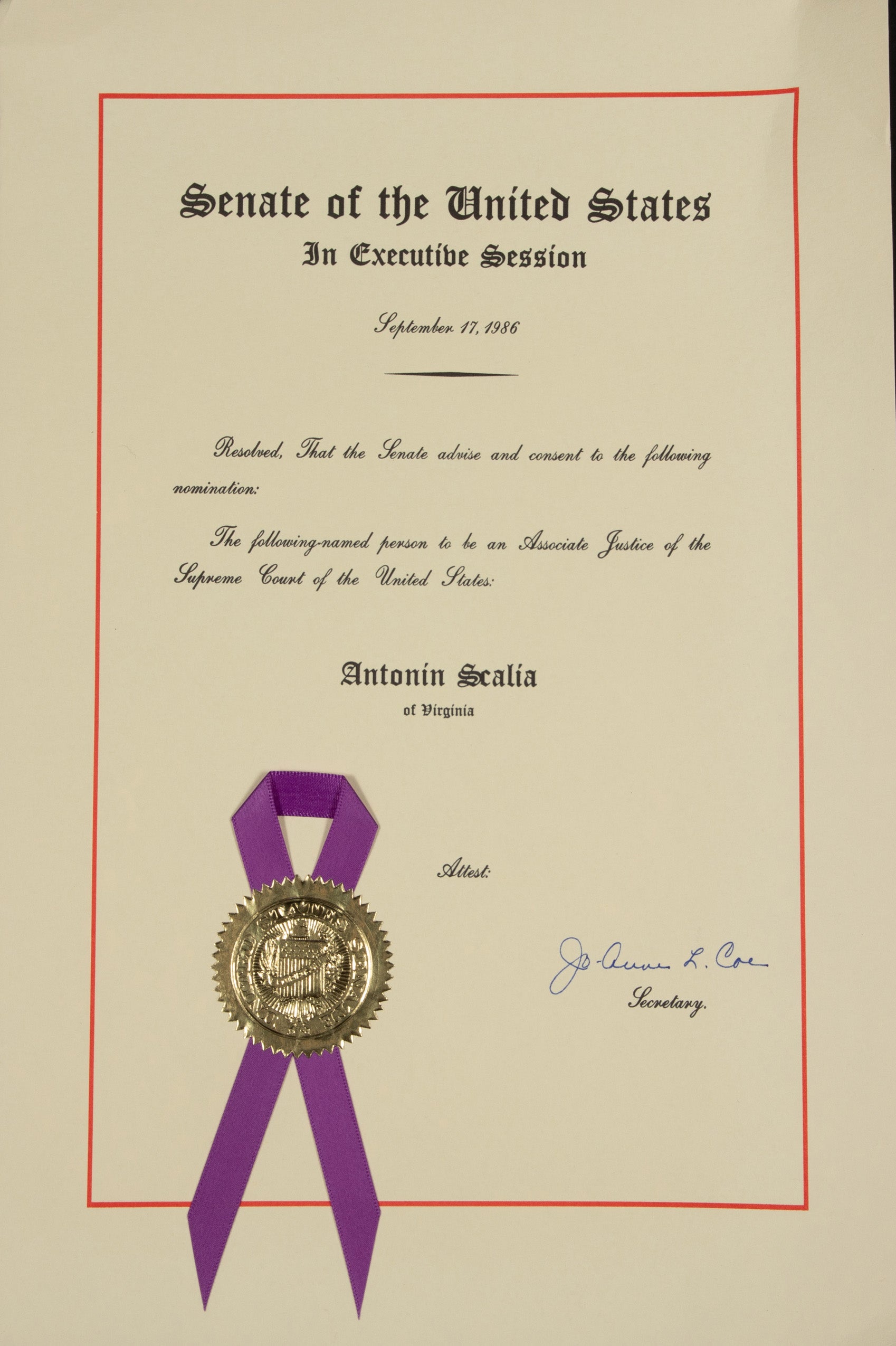

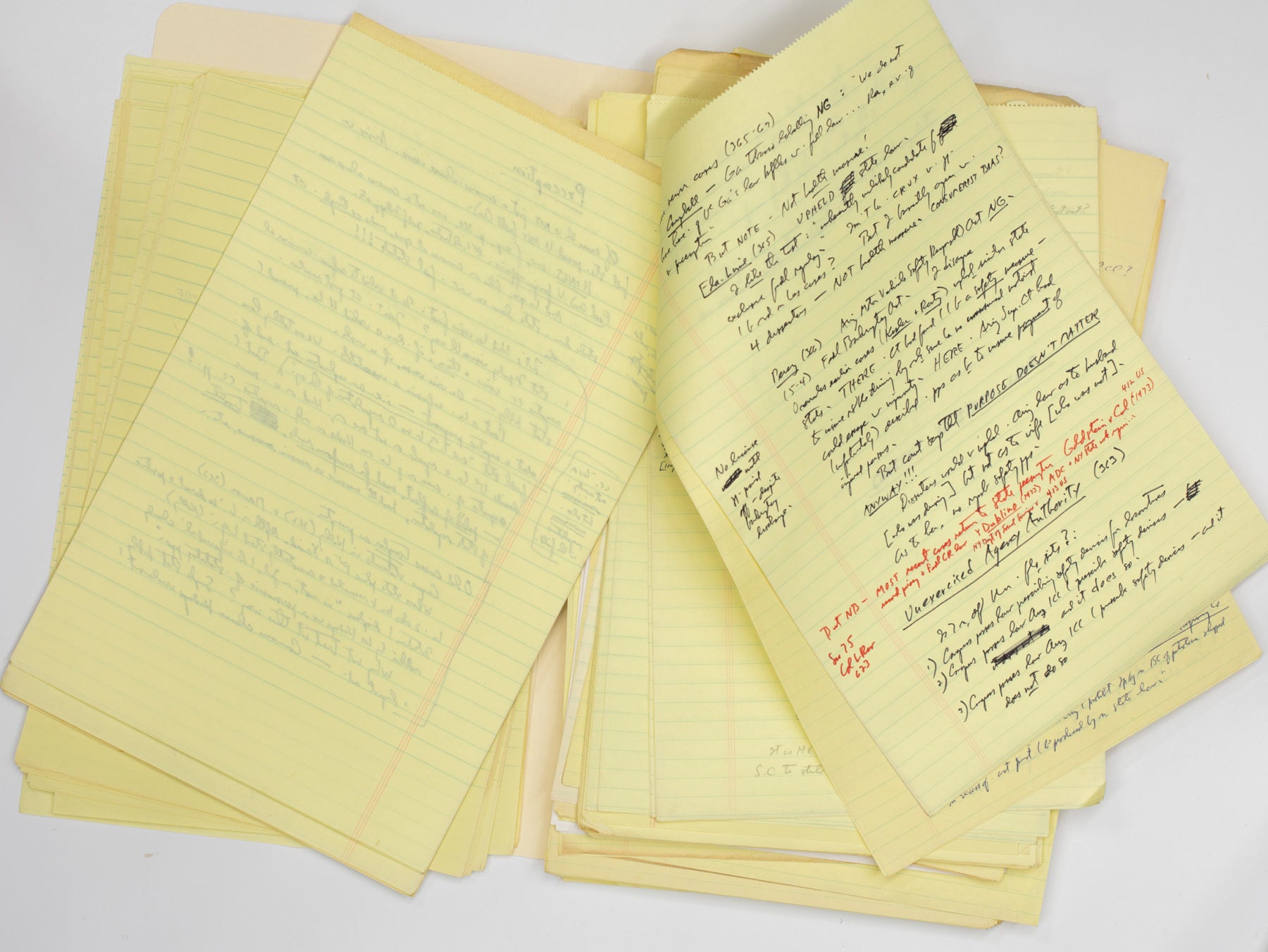

Irene Gates: We received approximately 400 linear feet of records from the estate, but as we process the collection, we’re consolidating and removing duplicative items, so it will likely end up being closer to 350 linear feet when fully processed. The majority—approximately 65 to 70 percent—of the collection consists of Supreme Court and Court of Appeals files. The remaining 30 to 35 percent contains correspondence, speaking engagement and event files, photographs, pre-judicial career material such as teaching files, ABA files, confirmation and nomination material, and miscellaneous other files.

HLT: As you have been working your way through Justice Scalia’s photographs, correspondence and other items, is there anything that has particularly surprised or interested you?

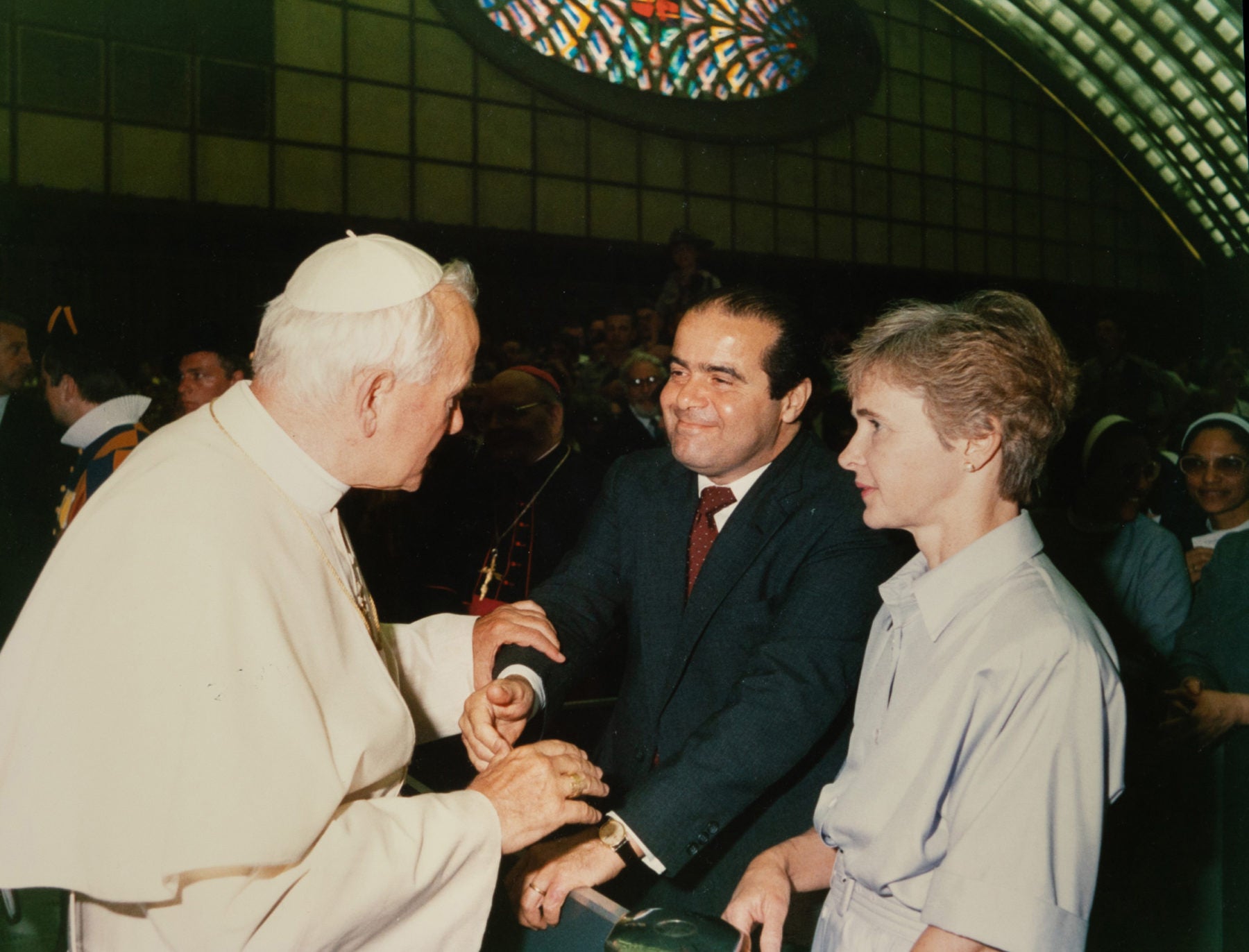

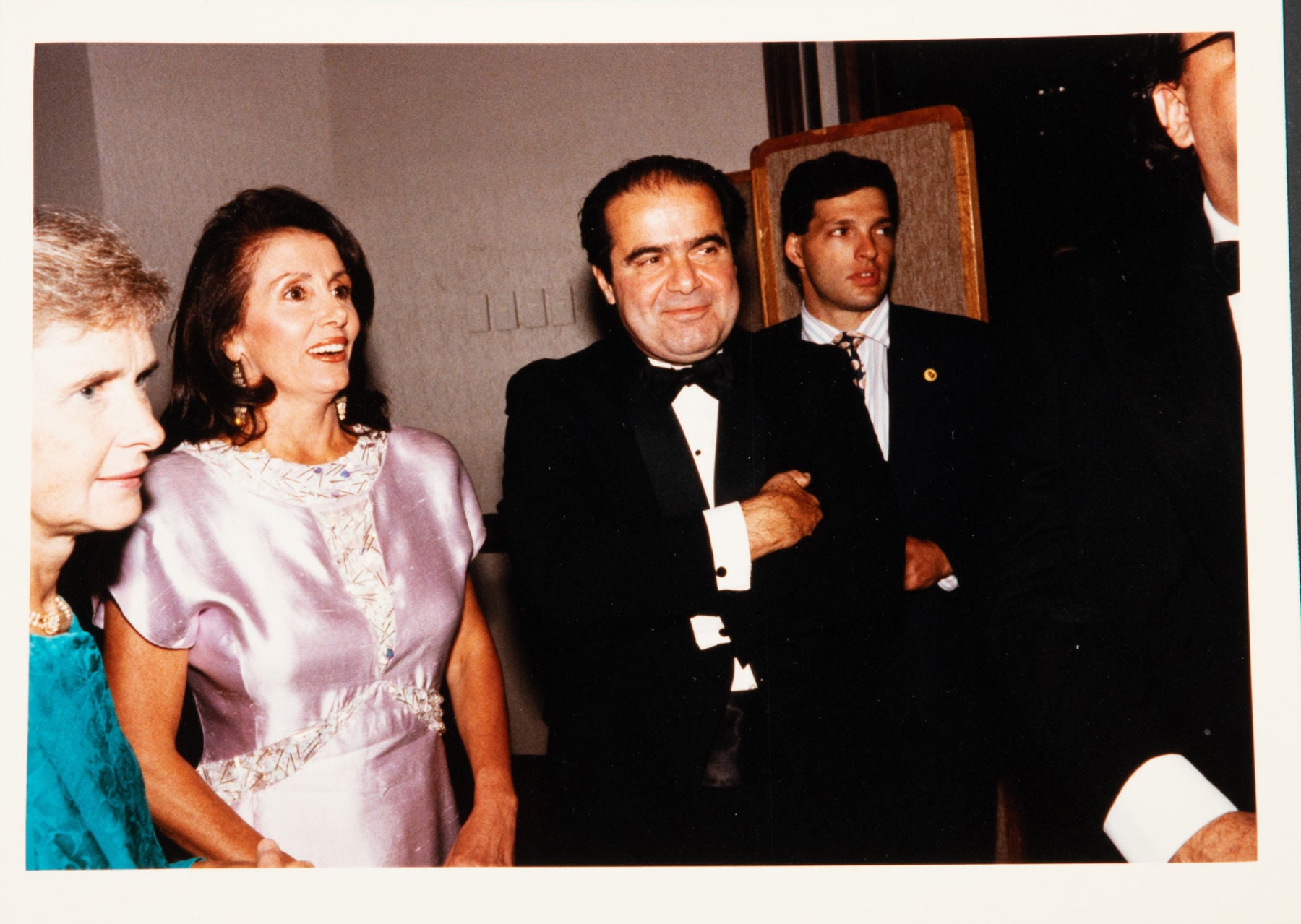

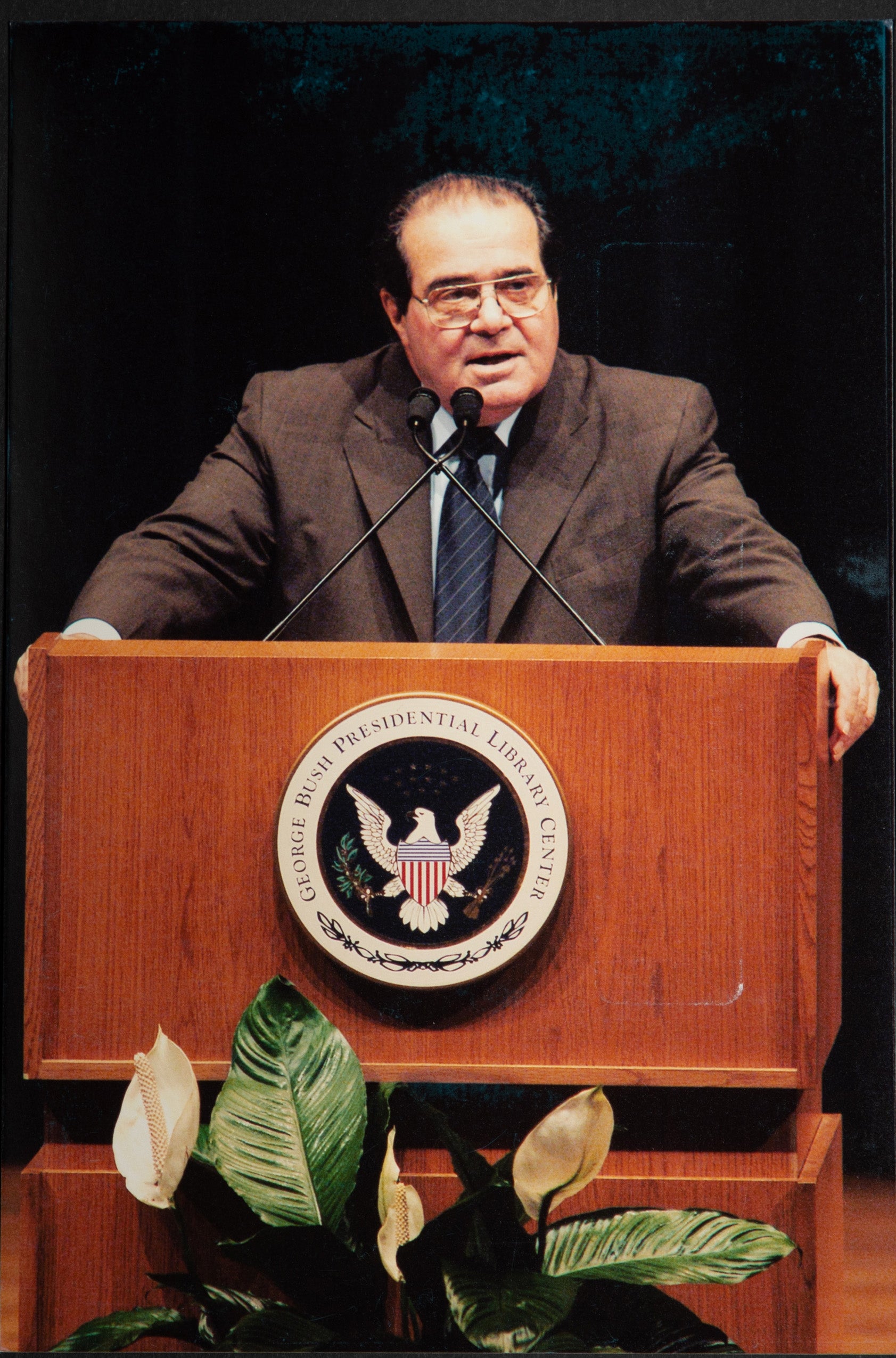

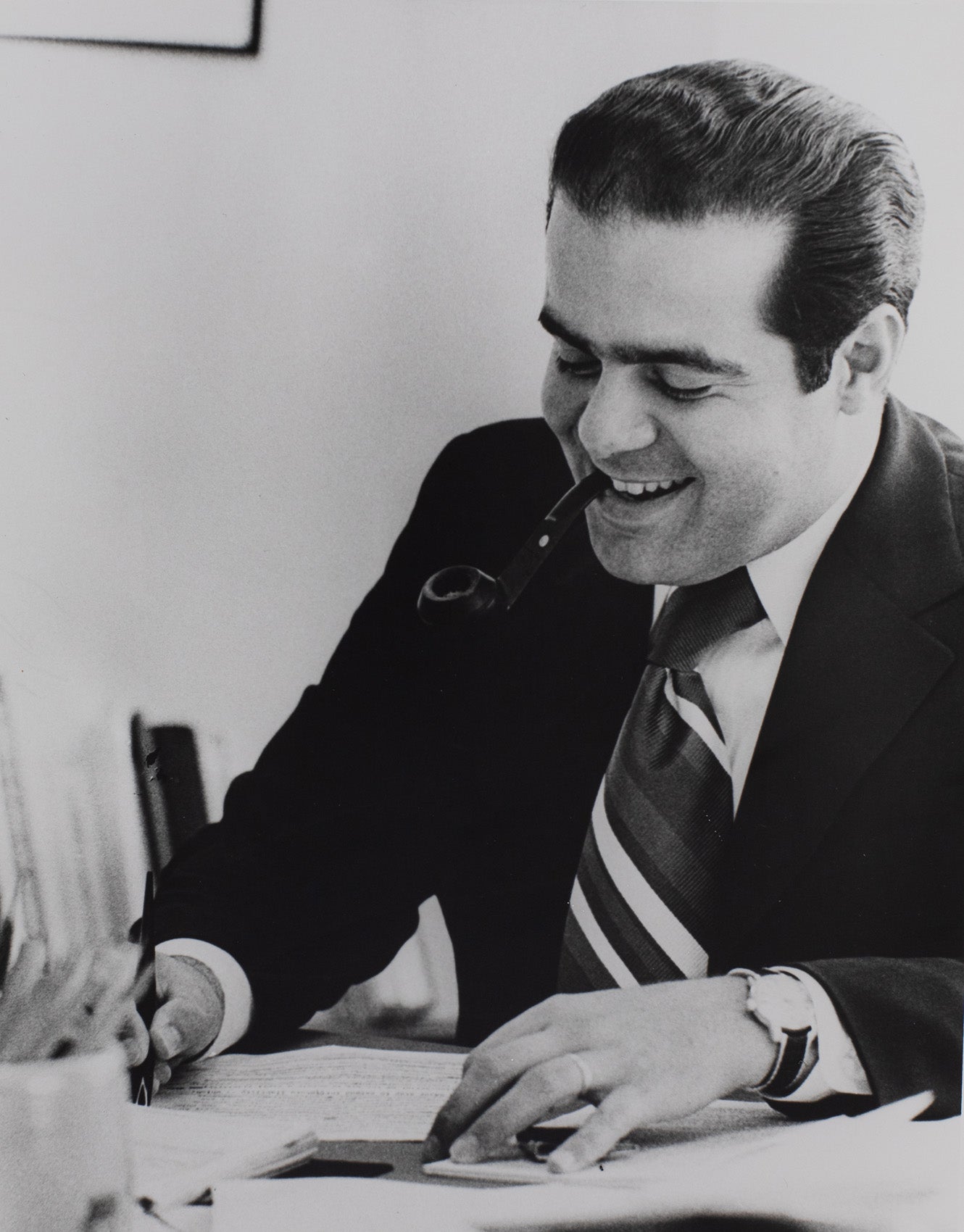

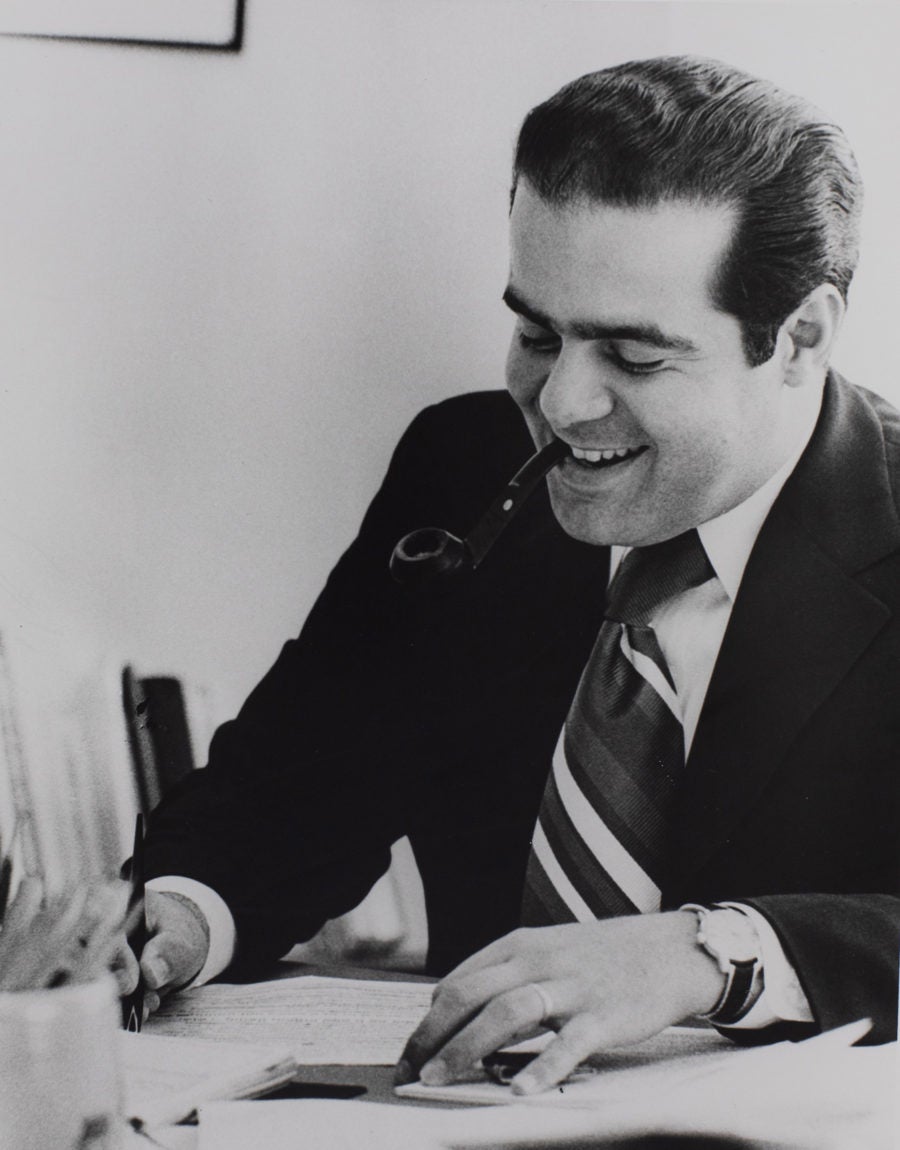

Gates: He had an incredibly full and active life. Maybe this is a given for a person of his stature, but I was struck by the number of events for which he was a speaker, or which he attended, and his travels, reflected in the photographs and the event files. He was such a public figure, and his influence extended far beyond the court.

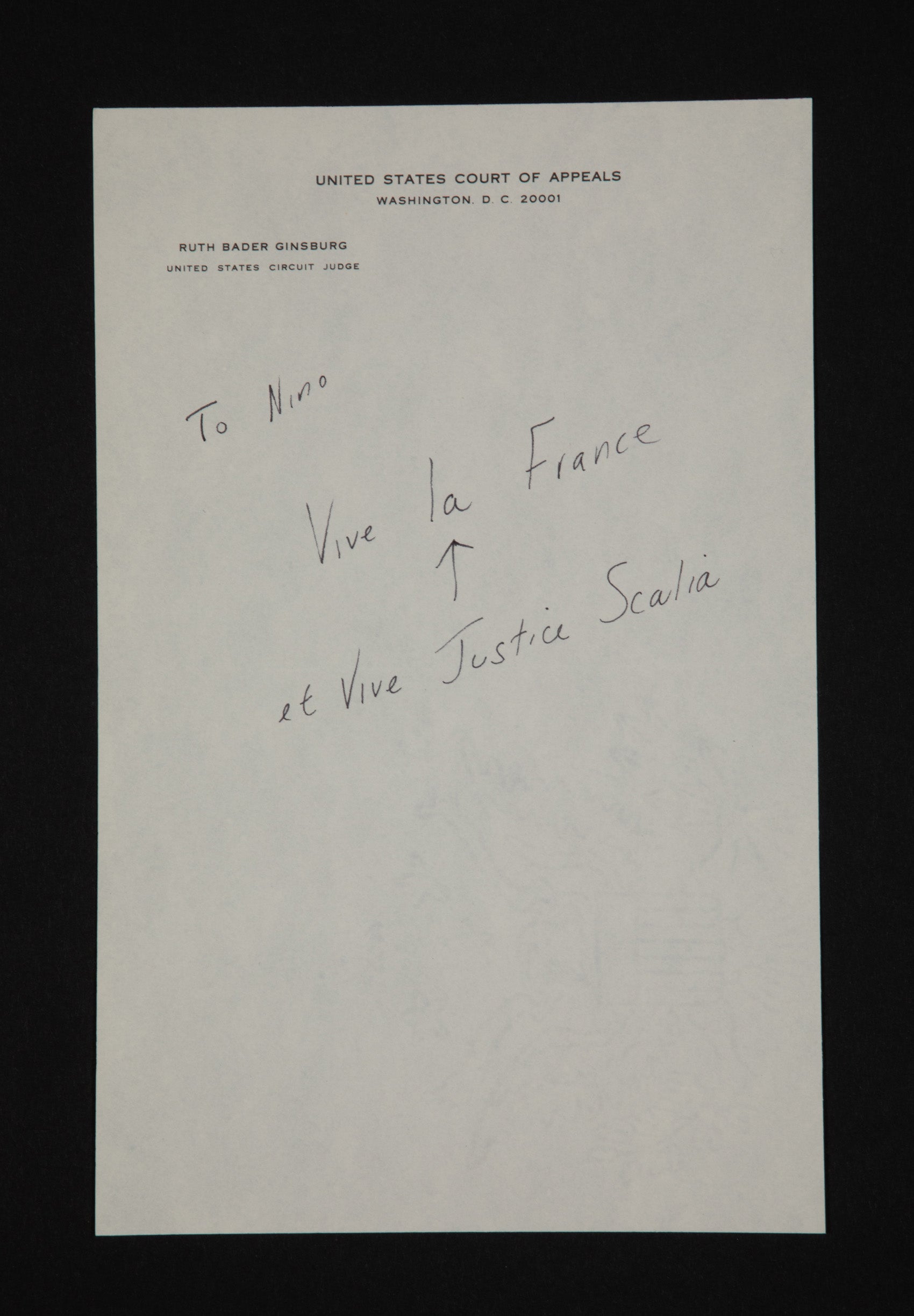

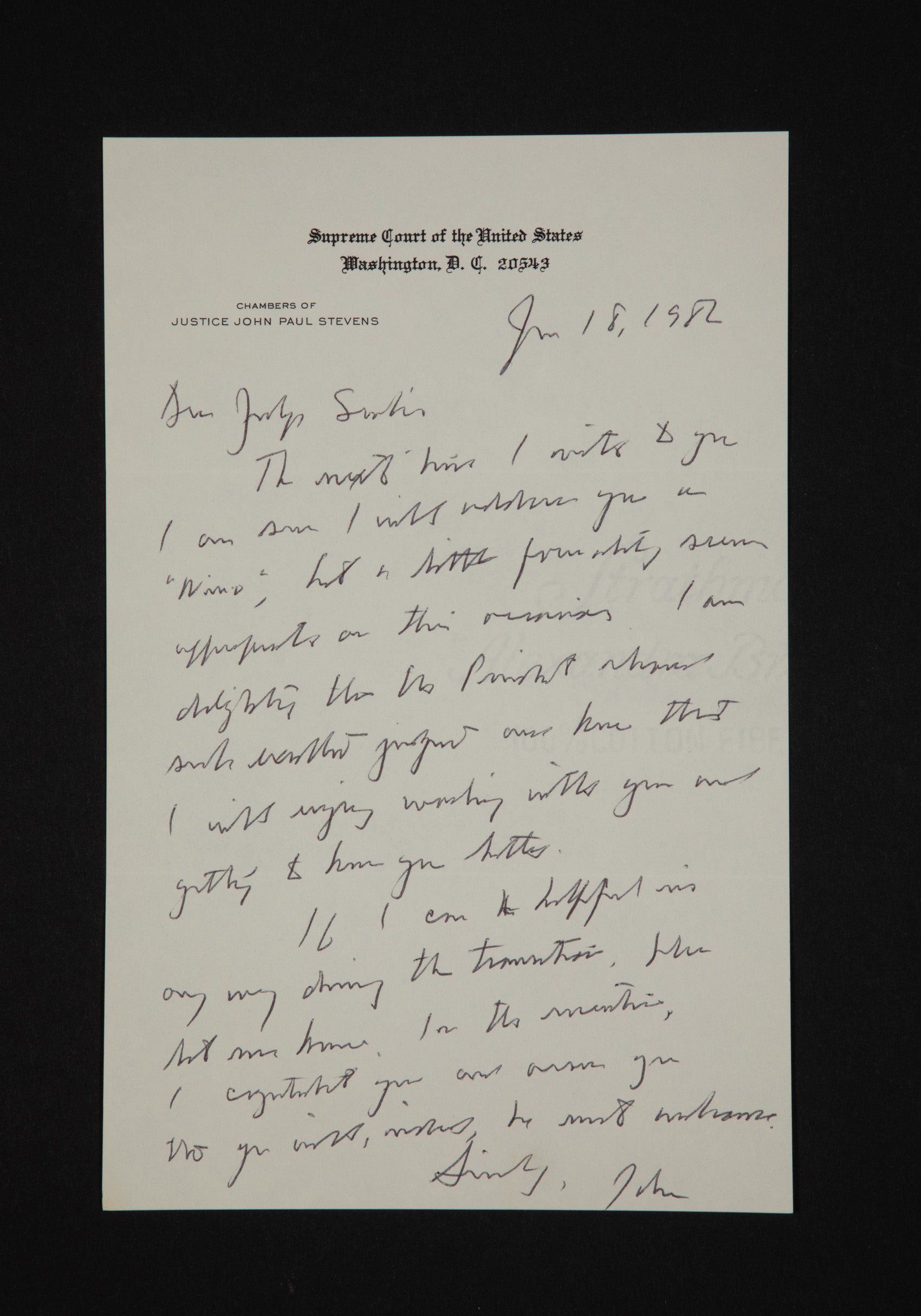

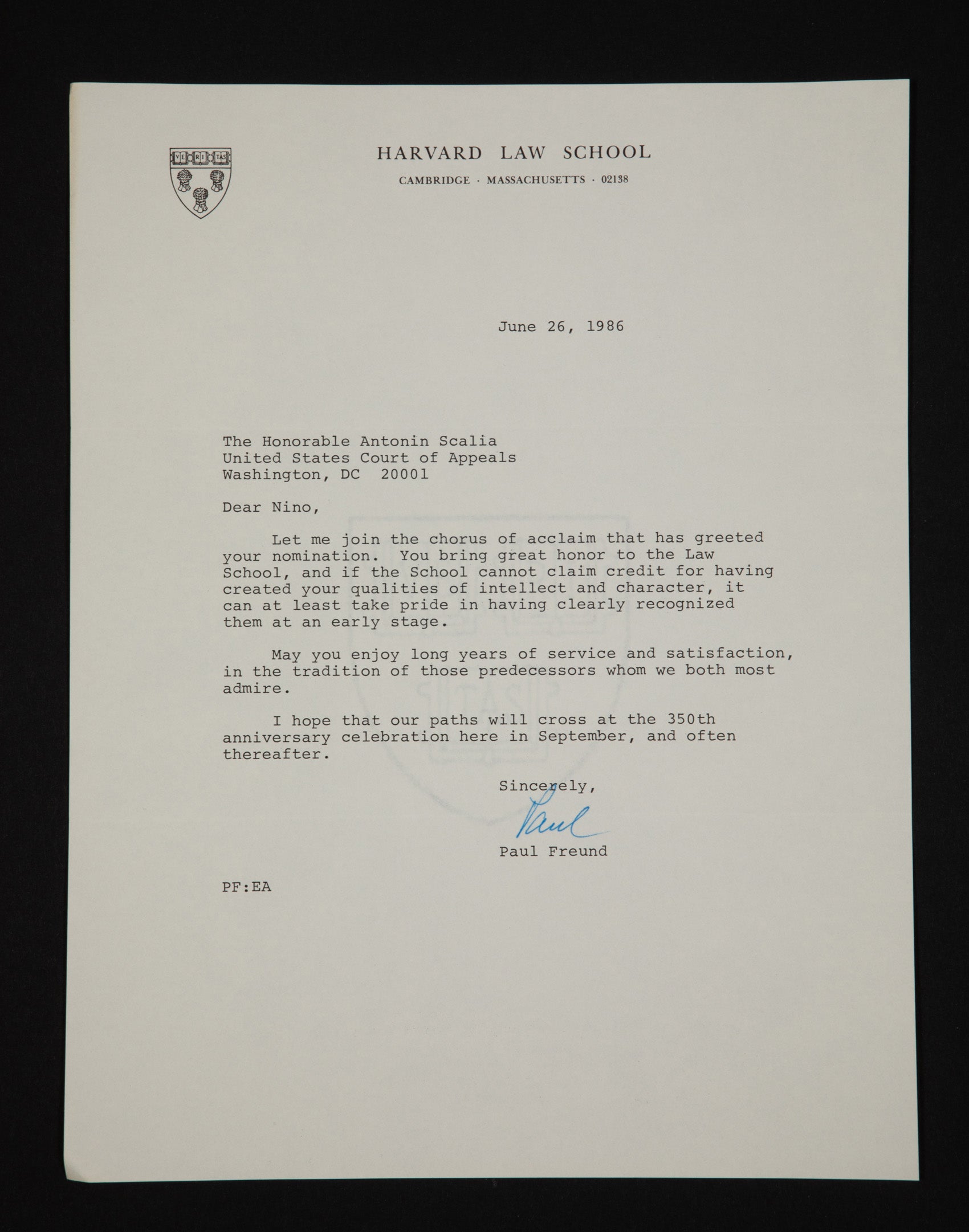

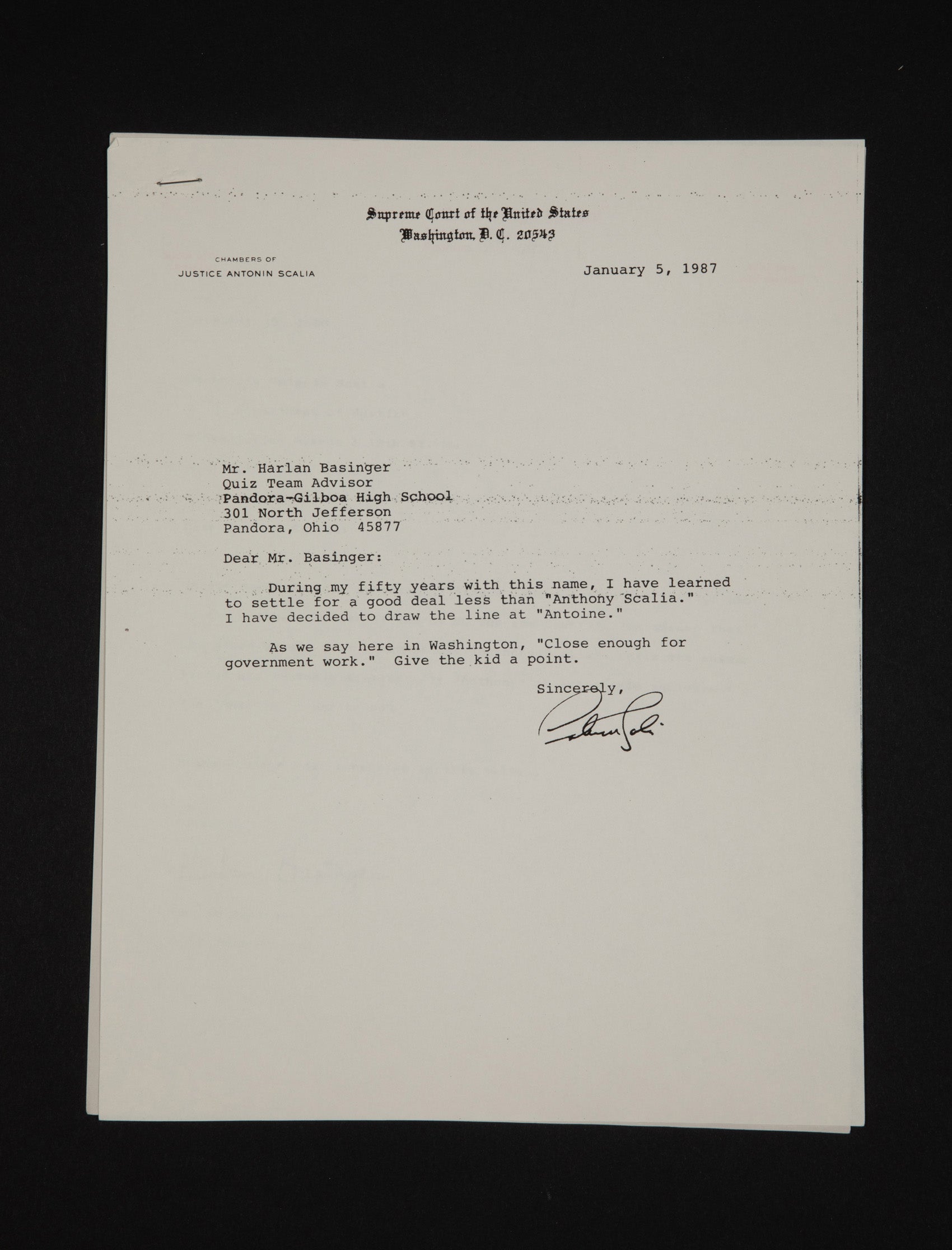

The congratulatory correspondence around his nomination to the Supreme Court is pretty fascinating too, and shows the breadth of the relationships he forged through different stages of his life and career. The letters include ones from academics, judges, politicians, people he grew up with, and Italian Americans expressing pride at his success.

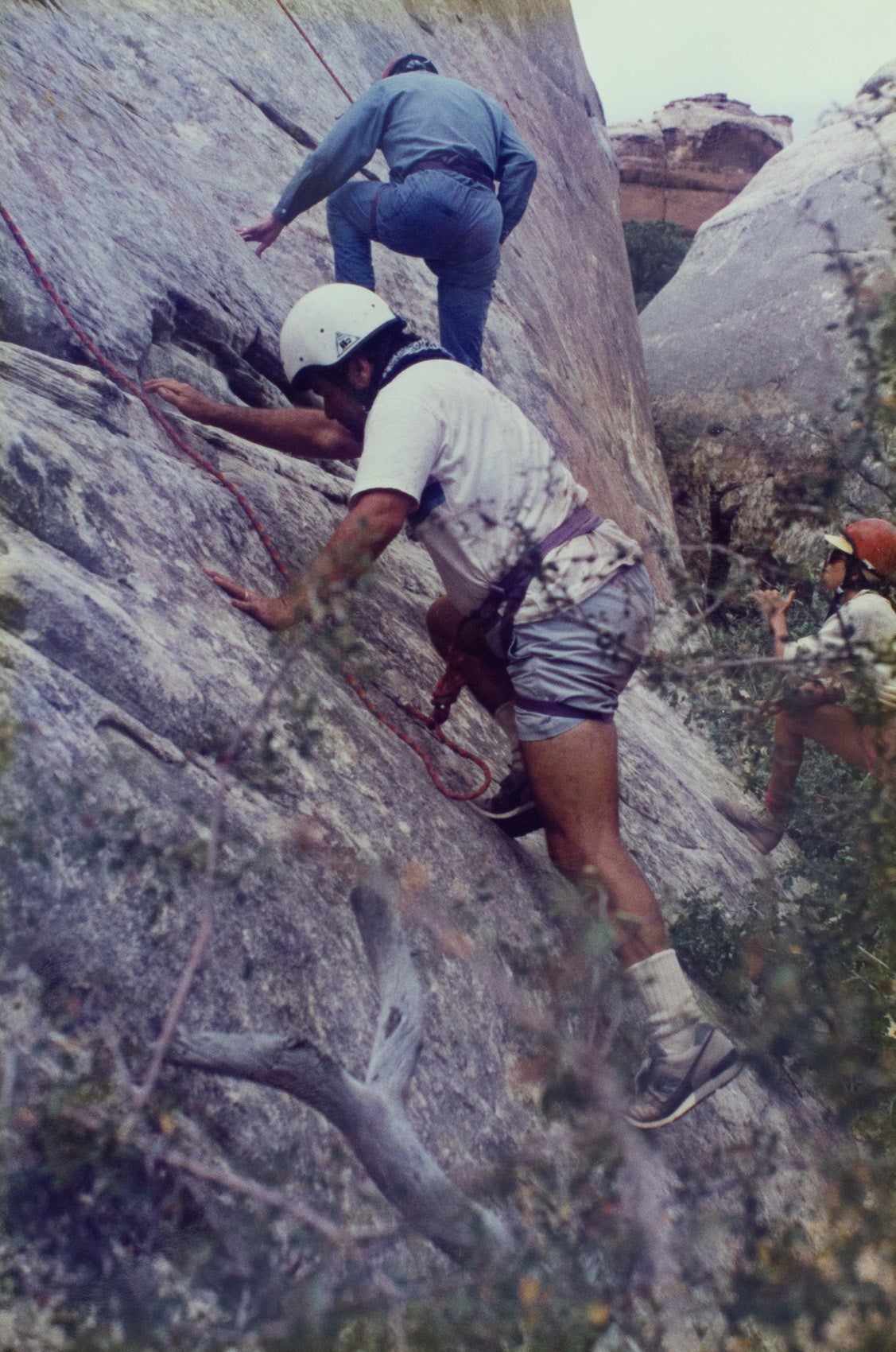

I was also surprised by how outdoorsy he was. He participated in Outward Bound, and there are many photographs of him on fishing and hunting trips.

HLT: Can you describe the process of cataloguing and ultimately making the collection available to the public?

Gates: The collection has been challenging to process because of the different types of restrictions. Some are time-based, and others are based on the lifetimes of individuals. I began by surveying the collection, trying to understand the contents while also evaluating them for restrictions. I then focused on processing that unrestricted material, which meant arranging the material intellectually and physically, inventorying material in the finding aid, and re-boxing and barcoding.

Our project assistant, Mike Muehe, and our department assistant, Carolina Quiroa-Crowell, did the final steps of refoldering and closely reviewing files. I’m now further along in the collection, working on the Supreme Court material that won’t be open for a number of years. I’ve also been working on a system that will allow the department to know exactly what files can be opened and when in the future.

HLT: Why is the collection not being released all at the same time? How does this compare to other collections of Supreme Court justice papers?

Ed Moloy: The release schedule for Justice Scalia’s papers is based on the provisions of use as described in the Deed of Gift. There are numerous restrictions detailed in the deed the overall result of which is the rolling release of the papers. The restrictions were developed as part of discussions between the Scalia Estate and the Harvard Law School Library prior to the donation. Though the collection’s restrictions will delay the complete opening of Justice Scalia’s papers for many years, we are thrilled already to be opening a portion of the collection less than three years after signing the Deed of Gift.

The provision to open the papers of Supreme Court justices on a rolling basis has been common since Justice Thurgood Marshall’s papers were opened immediately upon his death in 1993. Since then most justices have requested significant parts of their papers be closed as long as colleagues they served with are alive. Notable exceptions to this trend include Justice Souter, whose papers are entirely closed until fifty years after his death, and Justice Blackmun, who allowed his papers to be open five years after his death.

HLT: When will the next batch of the collection be opened?

Gates: We will open another year of Scalia’s correspondence, and speaking engagement and event files, from 1990, in early 2021. Also, about 50 percent of the case files from the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit are eligible for release this year, but we still need to do further review of them before they can open.

HLT: What is it like to oversee the papers of one of recent history’s most important Supreme Court justices?

Moloy: Someone working in the Law Library generally, and Historical & Special Collections specifically, is surrounded by and has access to one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of research materials for the study of legal history. Despite this rich work environment, the papers of Justice Scalia standout. He was one of the most influential justices of the last 50 years, and while processing his papers, one is very aware of the historic importance of the collection.

Library staff greeted the news of the donation very mindful of the faith shown in the Law School by the Scalia family who were entrusting us with the legacy of a beloved member of their family. The responsibility we took on—to both scholars and Justice Scalia’s family—when accepting the donation has not faltered and continues to serve as the foundation of our work to bring the Justice Antonin Scalia papers to light over the coming years.

HLT: Can you tell us a bit about the Harvard Law School Library archives?

Moloy: Historical & Special Collections’ chief mission is to acquire, catalog, preserve, and make available to researchers materials that document the history of the law in general and of Anglo-American law in particular. Historical & Special Collections holds over 10,000 linear feet of manuscripts, over 300,000 rare books, and more than 70,000 visual images.

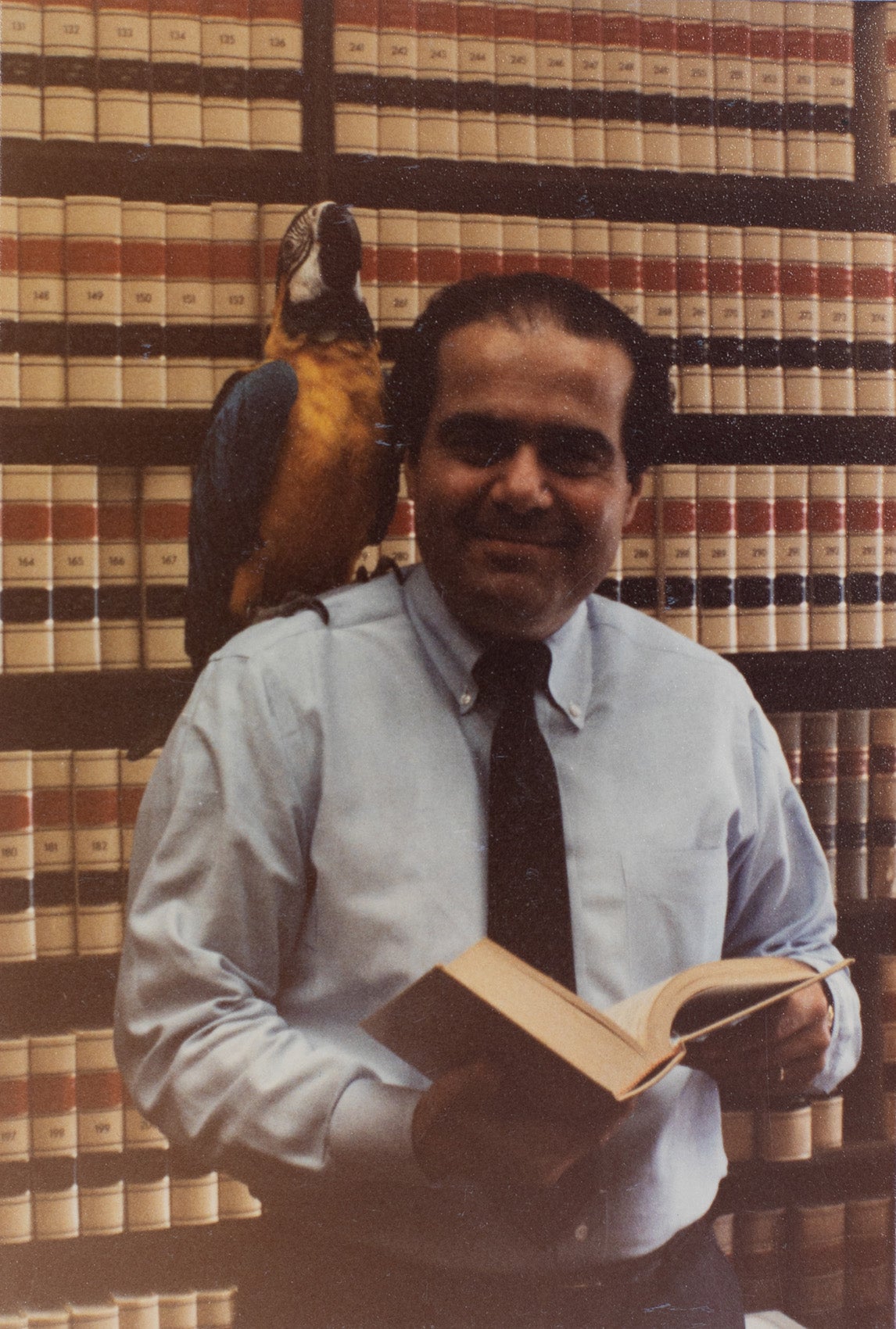

The Antonin Scalia papers are part of the Modern Manuscript Collection. The core of this collection consists of Harvard Law School faculty papers. Some of our most notable holdings include papers of Supreme Court Justices Joseph Story, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Louis Brandeis, and Felix Frankfurter. Additional collections include those of Judges Learned Hand and Henry Friendly, as well as Roscoe Pound, Christopher Langdell, Simon Greenleaf, Archibald Cox, and Manley Hudson.

HLT: Who do you find primarily uses these materials?

Moloy: Historians, legal scholars, and students from both Harvard and around the world either visit the Law Library to study and use our collections. In FY 2019, more than half of our users were non-Harvard affiliates. Researchers also benefit from our strong digitization program and can access many collections remotely.

HLT: What is your favorite part of the job of being an archivist?

Gates: So much of my work as a project archivist is back-end processing, and going through someone’s papers is a window into their world. I really love the different subjects I’ve learned about throughout my work with different collections. I usually read a lot about whatever subject I am working on, partly out of interest and partly to better understand the materials I am processing. During the first few months of this project, I read biographies of Scalia and a few other justices, and other books about the Supreme Court.

In the end, the most rewarding part of the job is seeing a collection you’ve worked on opening to the public. I’m really looking forward to helping researchers find the information they are looking for within the Scalia papers. I’m also really hoping that students at the Law School will come and use this resource, and am curious to hear their perspectives on this material.