With his surprising victory in the Iowa caucuses last Sunday, Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz ’95 solidified his status near the top of the GOP field. But in the background, the controversy over his birthplace and his eligibility for the nation’s highest office simmered on.

At the forum “Is Ted Cruz Eligible to Be President?” held Friday at Wasserstein Hall in Harvard Law School (HLS), two constitutional scholars debated whether Cruz’s birth in Calgary, Alberta, to a Cuban father and an American mother disqualifies him to serve as president.

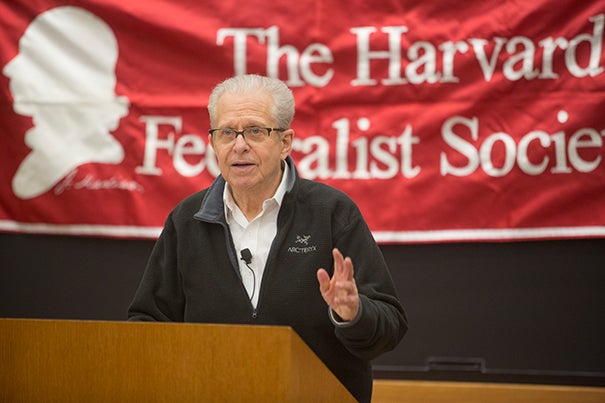

Laurence Tribe ’66, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor and Professor of Constitutional Law, who teaches at HLS, argued that Cruz is ineligible to hold the presidency, using what he called Cruz’s own strict interpretation of the Constitution.

“Cruz claims that the narrow, historical meaning of the Constitution is literal, except when it comes to the ‘natural born citizen’ clause,” said Tribe, who taught Cruz when he was a student at HLS in 1994.

The crux of the matter is that the Constitution, in Article II, Section 2, Clause 5, states that “no person except a natural born citizen” can be president.

Under English common law, upon which U.S. law was based, a “natural born citizen” would be someone born on American soil. For Tribe, according to this definition, Cruz does not qualify. He compared Cruz to Alexander Hamilton, a founding father who was born in St. Croix, Virgin Islands, but qualified as a U.S. citizen at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, and former presidential candidate John McCain, who was born in the Panama Canal Zone when it was under U.S. control.

“Unlike Cruz, McCain was born in U.S. territory,” said Tribe. “And unlike Cruz, McCain was born to two U.S. citizens, parents who had been deployed to the Panama Canal Zone by the military to serve the country.”

But for Jack Balkin ’81, a constitutional law professor at Yale University, Cruz is a “natural born citizen” because under U.S. immigration law in 1970, he automatically became an American because his mother was one. The law grants birthright citizenship to a child born overseas if one parent is a U.S. citizen.

“The question is: What was the law in 1970 when Cruz was born?” said Balkin. “The law in 1970 was that if one of your parents was a U.S. citizen and has established residency before your birth, you become automatically a U.S. citizen by birth.”

Tribe and Balkin did agree that cogent arguments could be made both in favor of and against Cruz’s eligibility by using different interpretations of the Constitution and existing laws.

Tribe said he’d be open to interpretations allowing a flexible reading of the “natural born citizen” clause. A self-described liberal, Tribe represented Democratic candidate Al Gore in Bush v. Gore during the dispute over the 2000 presidential election.

“As an unapologetic living constitutionalist,” said Tribe, “I’m someone who believes that constitutional terms of art, like ‘natural born citizen,’ can be flexible enough to accommodate changing national values, experiences, and practices. So I’m at least open to the view that Cruz should be deemed eligible under an expanded understanding of the ‘natural born citizen’ clause.”

For Cruz, a U.S. senator from Texas who was campaigning in nearby New Hampshire Friday in advance of Tuesday’s primary election there, his citizenship is settled law. But after Cruz’s surging victory in Iowa, his Republican rival Donald Trump, who came in second, renewed his attacks over the issue. Trump has joked that Cruz should run for office in Canada. Cruz renounced his latent Canadian citizenship when he ran for office in the United States.

Tribe and Balkin did agree that the matter is not settled.

“The question is anything but open-and-shut,” said Tribe. “In no possible sense has this issue been settled, either by the Supreme Court or political process or by popular consensus.”

Sponsored by the Harvard Federalist Society, the debate drew an audience that filled the room despite the snowstorm. Among those on hand was law student Chris Danello, who summed up the issue afterward.

“It exposed the divide not just on the right and the left,” he said, “but also among the many ways to interpret the Constitution.”

This article was published in the Harvard Gazette on February 5, 2016.