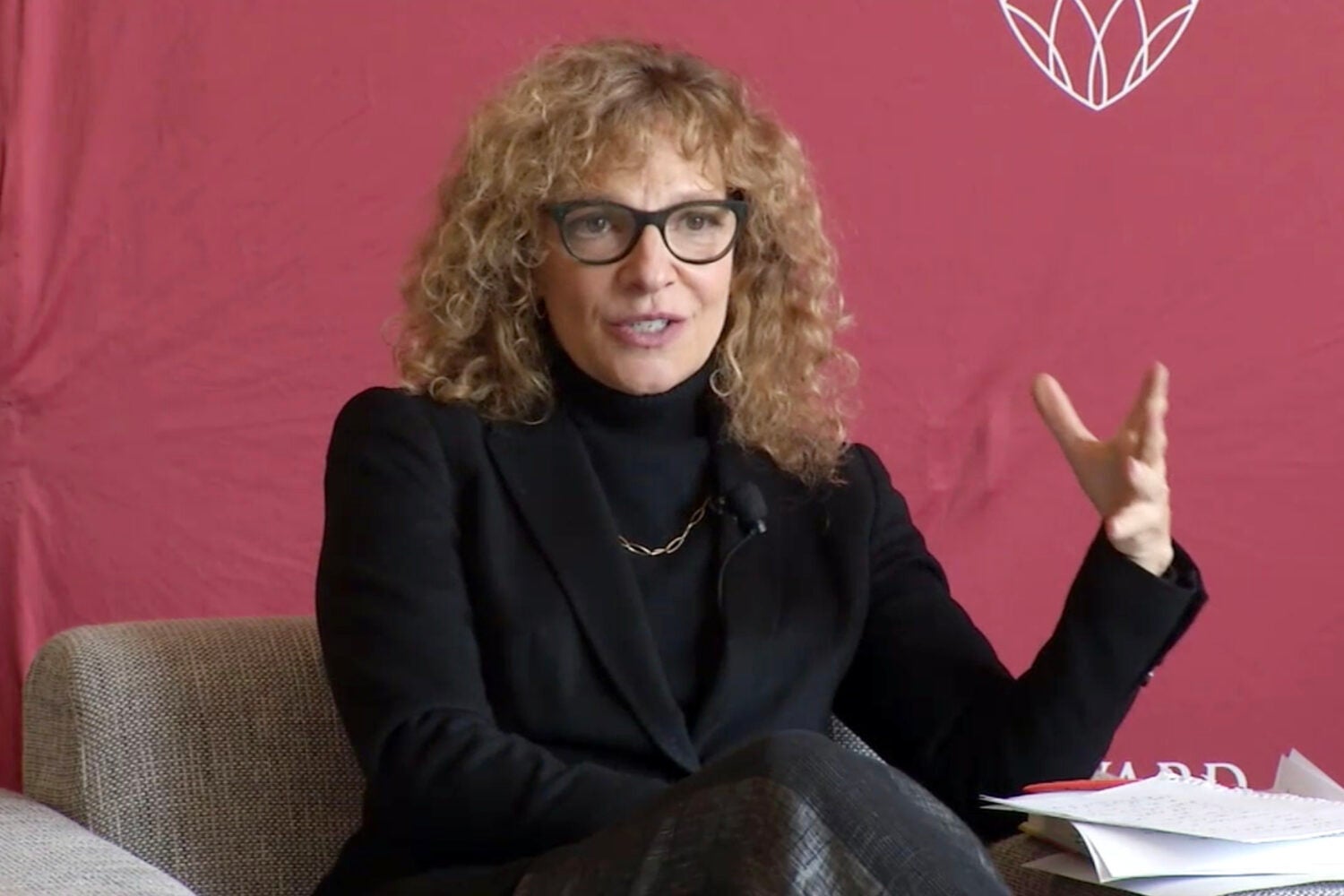

Speaking about her new book during an event at Harvard Law School, Diane Rosenfeld LL.M. ’96 contended that the law often does not help women escape violence at the hands of men. The lecturer on law and founding director of the Gender Violence Program at Harvard Law School referenced Supreme Court cases that struck down provisions of the Violence against Women Act and denied the right to enforce an order of protection. Her book proposes a different way to help women: the bonobo way.

The book, “The Bonobo Sisterhood: Revolution through Female Alliance,” provides a roadmap to eliminating male sexual coercion in humans based on the female-led social order of bonobos. It was inspired by a course Rosenfeld taught on theories of sexual coercion with Harvard University anthropologist Richard Wrangham, who joined her at a book talk sponsored by the Harvard Law Library on March 23. The basic bonobo principle, said Rosenfeld, is that “no one has the right to pimp my sister, and by pimp I mean harm, exclude, coerce, threaten, gaslight, abuse. … And everybody is my sister.”

Wrangham, whose research has focused on primate ecology, provided a contrast between chimpanzees and bonobos, similar-looking members of the ape family. Male chimps, he said, exhibit behavior that is more “humanlike,” including killing rivals and “conducting sexual violence as a routine practice,” whereas bonobos don’t kill each other, and sexual violence is absent. When a female bonobo is alarmed by an approaching male, she calls out to other females to come to her aid. In the bonobo sisterhood, he said, “Females in coalition defeat males.”

Female alliances can likewise be effective in humans, Rosenfeld noted, as demonstrated in the story of actor Ashley Judd, who helped spur the second iteration of the #MeToo movement when she and others spoke out to accuse film producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual misconduct. (Judd, who took a class with Rosenfeld when she studied at the Kennedy School, wrote the book’s foreword.) “The potential of female-female alliances to stop patriarchal violence is a real thing that we can recognize and activate in our own lives,” Rosenfeld said.

“The potential of female-female alliances to stop patriarchal violence is a real thing that we can recognize and activate in our own lives.”

She outlined her theory of patriarchal violence, which is enabled when the law can’t prevent the level of violence against women that is necessary to maintain a patriarchal social order. In a patriarchy, she said, women are socialized to believe that men will come to their aid. She advocated for women practicing self-defense, citing an expression by Gloria Steinem that the most important thing is to know you have a self worth defending. Rosenfeld spoke of a “transformative” experience taking a self-defense class with some of her students, which taught them to “unlearn these messages that you’ve been getting since you were born about femininity and weakness and needing to be helped.”

Groups of women can thwart patriarchal violence by banding together, just as bonobos do, to challenge male sexual coercion, whether in person or on social media, Rosenfeld said. To build a bonobo sisterhood, she said we should recognize that all women can be subject to patriarchal violence and share resources to protect them.

Everyone, men and women, can join the alliance, she said, adding that a patriarchal society can harm men as well as women. She hopes “The Bonobo Sisterhood” will motivate people to examine how the patriarchy has shaped their lives and to “make your world and the world of all your sisters better,” as she concludes the book.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.