In the fall of 1965, Spencer Boyer LL.M ’66 was the only Black student in Harvard’s LL.M. program when he was approached by two students in his constitutional law seminar with Professor Paul Freund. Frank Parker ’66 and Joseph Meissner ’66 were white students who would go on to renowned careers as civil rights lawyers. They were interested in starting a law review that focused on civil rights and progressive scholarship and wanted to know what Boyer thought.

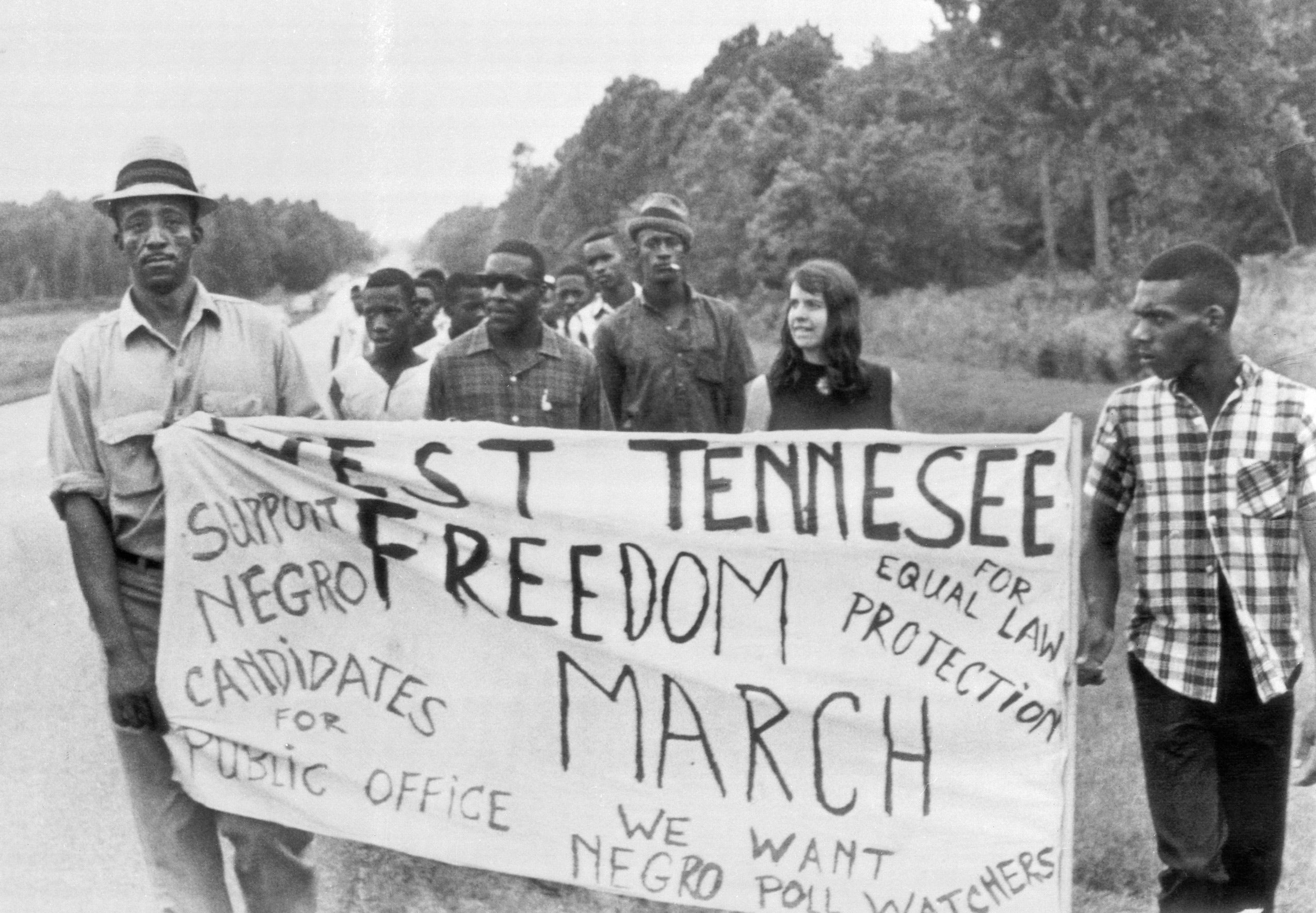

To Boyer, the timing couldn’t be more urgent. “It is virtually impossible to describe the political atmosphere and social tensions of just the first half of the 1960s,” Boyer recalled in a speech at HLS in 2000 in a celebration of the 35th anniversary of the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review (CR-CL), the journal that he and the others founded. Freedom riders were being beaten or murdered as they sought to enfranchise Black voters in the South; President John F. Kennedy and Malcolm X had been assassinated; and the Vietnam War was escalating alongside protests against the draft. By comparison, “what’s happening today would be about a two on a Richter scale,” Boyer says now.

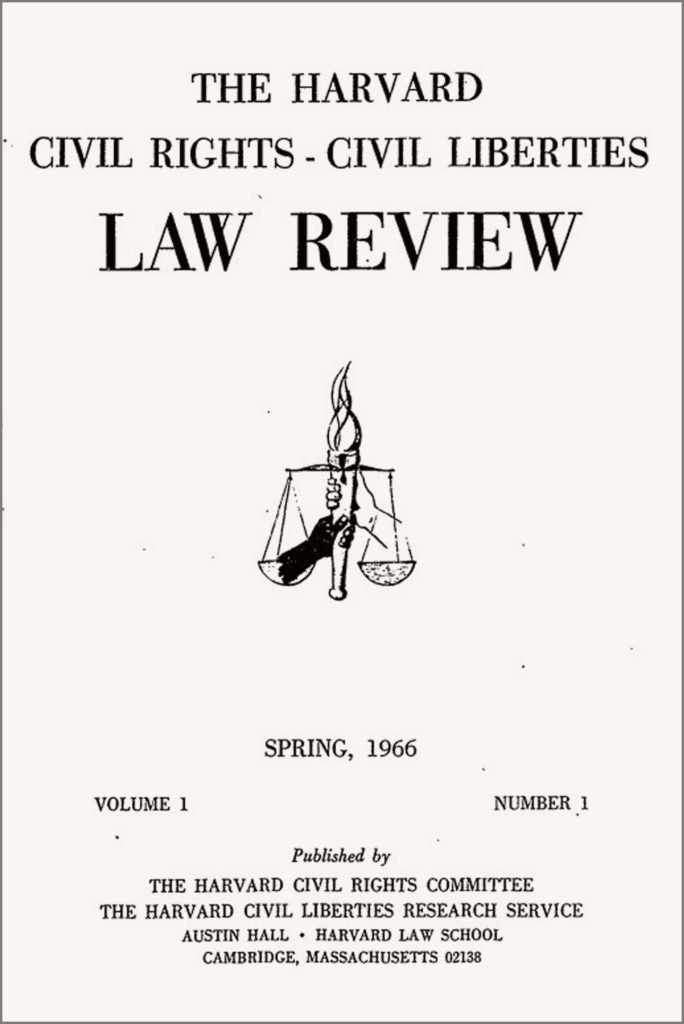

The first issue of Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review launched in spring 1966. According to the founding editor, the cover depiction of a white hand displacing a black hand on the torch of freedom was a giant misstep — one that was rectified in subsequent issues.

At that time, HLS was just beginning to address its own racial disparities. In 1965, the school had 30 Black students, compared to only two in 1963. As he talked with Meissner and Parker, Boyer, who graduated from Howard University before getting his J.D. at George Washington University Law School, imagined a journal based on the Howard Law Journal, which focused on civil rights and what was then called “the race problem.”

“People were looking to the white intelligentsia to come up with solutions for black folk and the ‘race problem,’” remembers Boyer, who in 50 years as a law professor at Howard earned numerous awards for outstanding teaching, is a leading attorney and scholar in entertainment law, and has represented many community and public interest organizations. “But the ‘race problem’ was not a problem of the Black race but rather the use of white law as a cudgel against Black enfranchisement, equality, and prosperity. I said, let’s have a journal that provides Black lawyers with legal arguments to defend against discrimination in our legal system and processes.”

There were only three law journals at HLS at that time, including the Harvard Law Review, and all were heavily oriented toward corporate and business law, Meissner and Boyer recall (Parker died in 1997.) The trio envisioned a journal “dedicated to promoting ‘revolutionary law,’ which was meant to focus on using progressive law actively in order to make a better world for all,” says Meissner, whose career included serving more than 15,000 clients and 250 community groups as a legal services lawyer in Cleveland, Ohio. Importantly, CR-CL would offer students a venue for progressive writing and thought. “The review was meant to use the talents and writing abilities of all Harvard Law students,” says Meissner, “not just the few who got selected for the Harvard Law Review.”

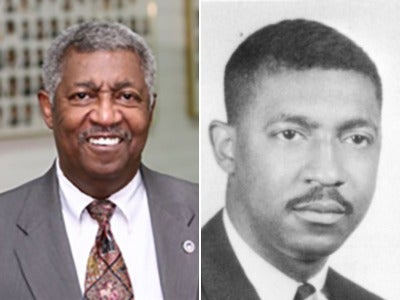

Spencer Boyer (pictured here alongside his 1966 Harvard Law School yearbook photo) taught for 50 years at Howard University School of Law in Washington, D.C.

But they needed the HLS imprimatur — and funding. Boyer volunteered to meet with then Dean Erwin Griswold ’28 S.J.D. ’29. “At that point I wasn’t cowed by the mystique of the dean, so I said, ‘Fine, I’ll go talk to him,’” recalls Boyer, who was prepared to defend the necessity of a progressive law journal. “But [Griswold] just said, fine, how much do you need?” and agreed to Boyer’s $600 request. As Boyer recalled in his 2000 speech, when Boyer turned to leave, “Dean Griswold said, and I quote, ‘One last thing, Mr. Boyer. If you are going to use the name Harvard on your journal, make sure it does Harvard proud.’”

Has it ever. As it celebrates its 55th year, CR-CL is one of the nation’s leading progressive law journals, widely cited by scholars and practitioners. With more than 200 student members, it is the largest student journal at HLS with such notable alumni as HLS Professor Cass Sunstein ’78 and President Barack Obama ’91, who was also editor-in-chief of the Harvard Law Review.

“Our goal has and continues to be to center marginalized voices,” says Sararose Gaines ’22, co-editor-in-chief for Volume 57. Prior to the founding of the Latinx Law Review in 1995, CR-CL was the only HLS journal dedicated to highlighting Latinx voices. Gaines notes that CR-CL works to publish Black and Brown voices alongside other specialized journals including the Harvard BlackLetter Law Journal. CR-CL focuses on tangible ideas, notes Natassia Velez ’22, co-editor-in-chief alongside Gaines. “For me, the dream of CR-CL is to be the place where marginalized voices are uplifted and those ideas become part of the fabric of our nation.”

CR-CL’s first issue, published in the spring of 1966, included student-written articles on such topics as the federal government’s power to protect Black people and civil rights workers against privately inflicted harm. CR-CL “opened up the law review writing arena for all students and especially for the many minority students including those from Afro-American backgrounds who began to be admitted to Harvard Law during our period of the 1960’s,” says Meissner. But the first issue had a giant misstep, says Boyer. The cover depicted two hands — one Black, one white — holding a torch of freedom, with the white hand on top. Boyer insisted the position of the hands be reversed in subsequent issues to emphasize CR-CL’s ethos of “white folks helping Black folks, but not white folks answering the questions for Blacks,” he says.

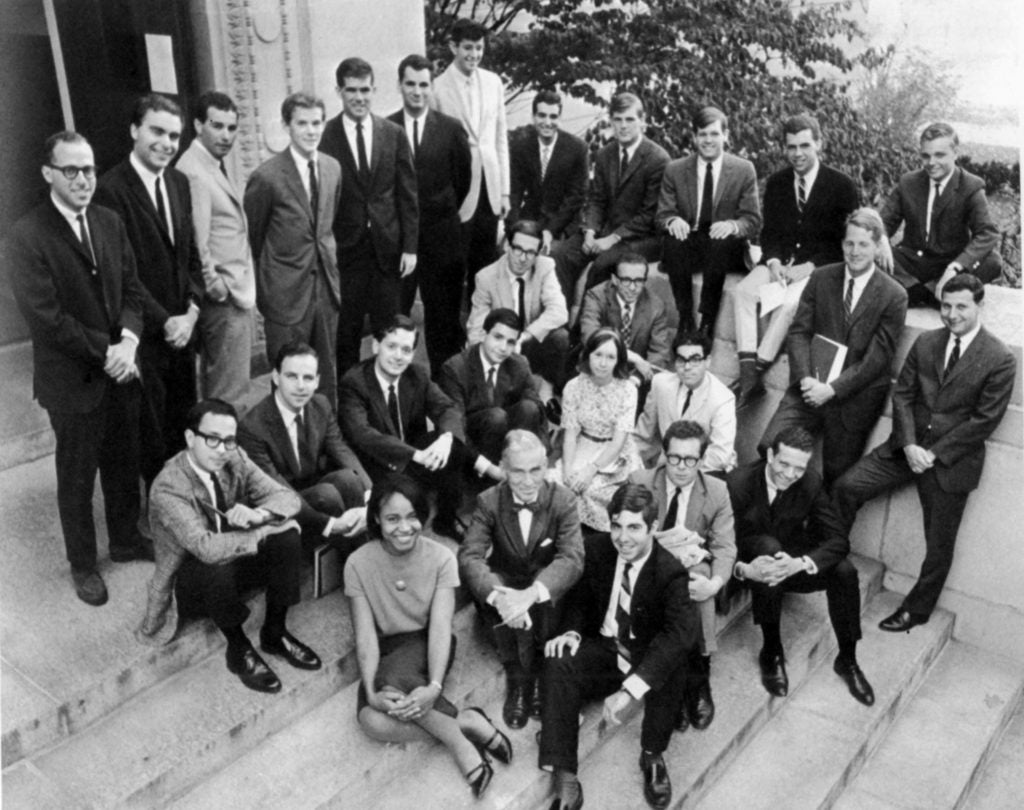

A group photo of members of the Harvard Civil Rights Committee in 1966. Harvard Law Professor Mark De Wolfe Howe ’33 (center) is seated next to Joseph Meissner ’66 (right foreground) and Frank Parker ’66 (in black glasses, behind Meissner).

“For 55 years, when people ask us what do you believe, we say we believe in publishing progressive voices. We are very unapologetic about that and we have not compromised on that,” says Armani Madison ’21, who, along with Mo Light ’21, were two Black men serving as editors-in-chief for CR-CL Volume 56, along with Alexandra Wolfson ’21 and Caroline Milosevich ’21.

In preparing for CR-CL’s 55th anniversary conference in March 2020, one of the last major events at HLS before the pandemic shutdown, Madison learned of Boyer’s central role in shaping its mission and contacted him at Howard, where he is professor emeritus after retiring in 2016. In inviting Boyer to write a forward for Volume 56.2, which will be published 55 years after CR-CL’s first issue, Madison wrote, “At our roots, we are a journal founded out of the Black freedom struggle, during the Civil Rights era, and, as we continue to evolve and expand, we should honor and remain unapologetic about the charge that this legacy provides us with.”

Boyer immediately agreed. “I’m very, very proud of the journal,” says Boyer, who taught more African-American lawyers than any other law professor, over 5,000 during his five decades at Howard, he says. Since its founding, CR-CL has published at least 84 articles on racial justice, 94 on LGBTQ rights, 94 on human rights, 191 on criminal justice, and 79 on voting and education, Boyer says, adding, “In my furthest contemplation, never could I imagine it would have such an influence on American law. Whenever people ask me, what have you done in life, being a co-founder of CR-CL is one of the first things I mention.”

CR-CL’s role as a leading progressive journal is more essential than ever, adds Boyer, who is concerned about what he sees as current attacks on civil rights, especially in the area of voting rights. “That’s why we need this journal, to deal with carrying the battle forward.”