The storming of the U.S. Capitol on Wednesday by supporters of President Donald Trump attempting to block the certification of the Electoral College vote has shocked people around the nation and around the world. It has few historical parallels, says constitutional law expert Sanford Levinson.

Harvard Law Today reached out via email to Levinson, a visiting professor at Harvard Law School in the fall and W. St. John Garwood, Jr. Centennial Chair in Law at University of Texas Law School, to put the breaching of the halls of Congress in perspective.

Harvard Law Today: Can you cite any historical parallels? Are there examples of angry crowds assaulting the Capitol building, other government facilities or the institutions of government generally?

Sanford Levinson: There are lots of parallels in the states, including the relatively recent march on the Michigan capitol by armed protesters against wearing masks and other policies adopted by the Michigan governor. And one of the banner events of the 1960s was a march on the California state capitol by Black Panthers brandishing weapons, as was their right under California law. (That was changed shortly afterward.) The difference, of course, has to do with the “angry crowd” actually storming the building and trying to take over. And I don’t think there is any parallel in our national history.

HLT: How about the 18th century Shay’s Rebellion in Massachusetts, in which citizens took up arms against the state government to oppose what they viewed as excessive tax collection efforts?

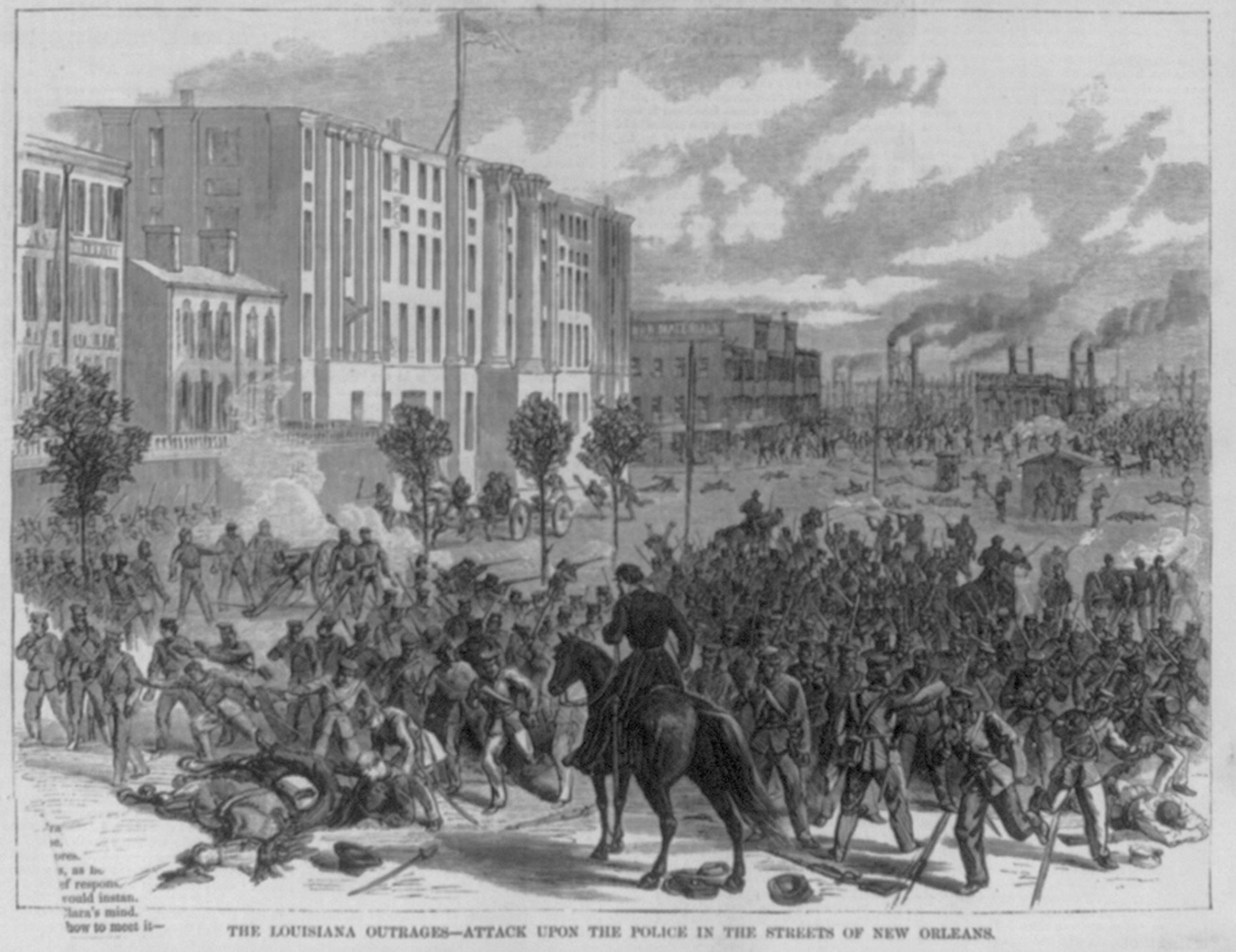

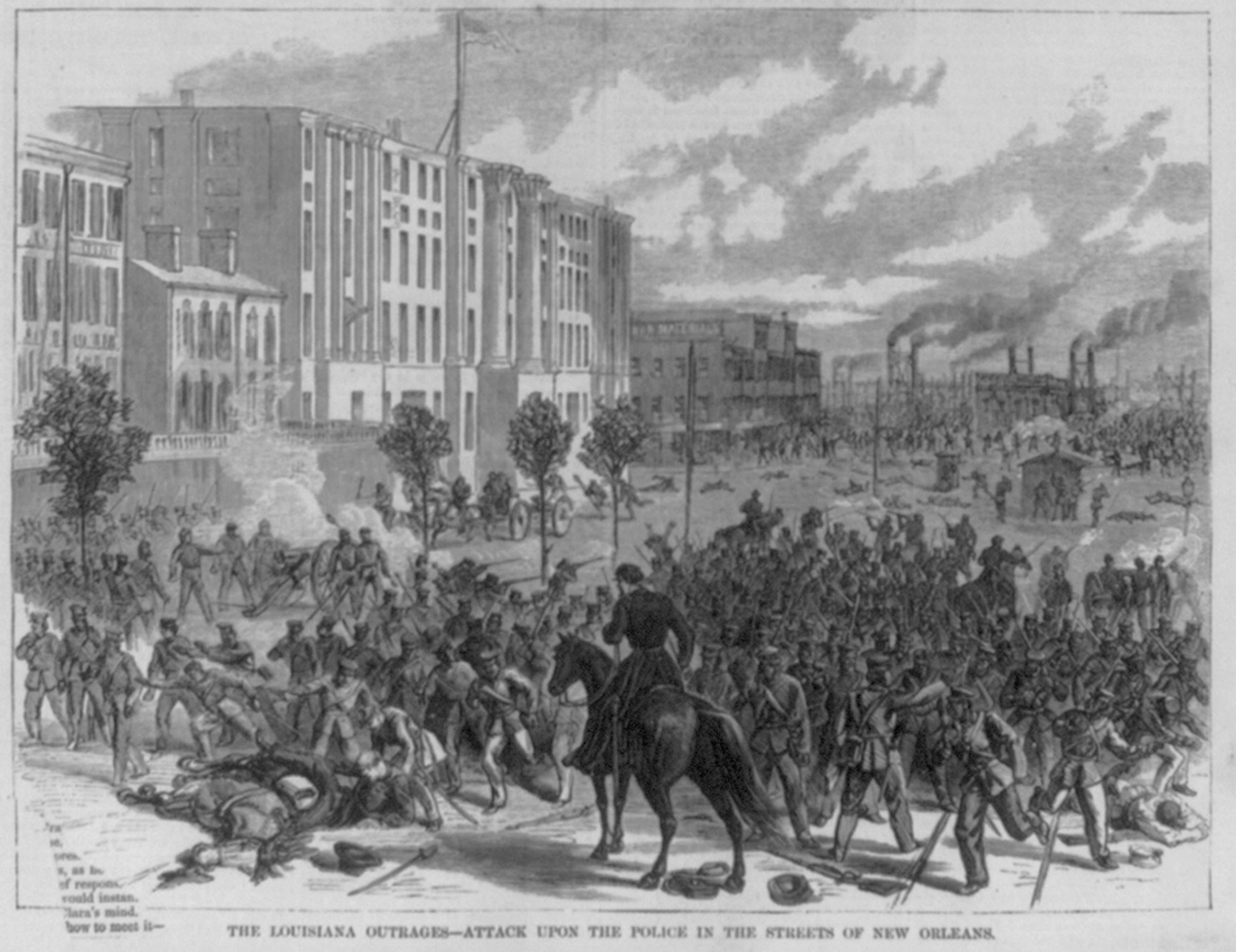

Levinson: Those who opposed Shay’s Rebellion might see a similarity. Or the Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island in 1842, which involved, ultimately, a failed march on the state armory. There was also the rebellion in New Orleans led by the aptly named White League that (unsuccessfully) tried to overthrow the Reconstruction government in Louisiana. One could say that Dorr and the White League were genuine attempts at revolution, whereas Wednesday’s event was a grim form of political theater in which no one could seriously believe that they would in fact take over and form a new government, as might have been the case in Louisiana and Rhode Island had those efforts not been resisted.

HLT: Are there parallels to the British assault on Washington, D.C. in 1814? Or is it different because that was a foreign force?

Levinson: It’s different not only because it was foreign, but also because it was a serious act of war designed, at a maximum, to overthrow the U.S. government or, more likely, simply to place the U.K. in a maximally advantageous position to negotiate the peace terms. And, incidentally, it could be viewed as retaliation for the U.S. burning down what was then the British Canadian capital of York. Some might also compare it to the September 11 attack, also a spectacular piece of terrorist theater that was not designed to overthrow the U.S. government, but was intended to (and most certainly did) send a very jarring message of anger and vulnerability.

HLT: During the Civil War, Washington D.C. was turned into a fortress against invasion, but Lincoln famously had difficulty reaching the city and, in 1864, he witnessed an assault on its outer defenses. And under Hoover, during the early portion of the Great Depression, a bunch of homeless World War I veterans set up camps outside the Capitol — Hoovervilles — to protest their condition. Is that relevant?

Levinson: The Civil War, again, was a genuine war, though one can doubt, incidentally, that the Confederates wanted to overthrow and take over the reins of national government instead of “simply” being able to leave the Union. The Hoover episode could be viewed as simply one among many “marches on Washington” (think of August 1963) designed to “make a powerful statement.” Again, the vital difference is that neither the Hoover demonstrators nor the Civil Rights Movement marched on the Capitol to try to take it over. Some of the Vietnam marches were provocative in marching on the Pentagon or by Nixon’s White House, but boundaries were kept.

Whether or not the protesters/insurrectionists should be tried, convicted, and have the book thrown at them is, I think, a matter for political debate. As a matter of cold fact, I think one could argue that as an ‘insurrection,’ it was a stunning failure.

-Sanford Levinson

HLT: What can we learn from these previous incidents or others that you might have in mind?

Levinson: What I think we should learn is that law, per se, may not be most relevant category of analysis. It would be regrettable if the discussion turned into a debate about whether the technical requirements of “incitement,” “sedition,” etc. were met. (Was Donald Trump’s egregious speech protected by the First Amendment, for example? I think many lawyers would say yes.).

Instead, it should be interpreted as a profoundly political incident that tells us a lot about the current state of American politics. Whether or not the protesters/insurrectionists should be tried, convicted, and have the book thrown at them is, I think, a matter for political debate. As a matter of cold fact, I think one could argue that as an “insurrection,” it was a stunning failure. There is no evidence at all that the “brave warriors” in fact inspired many Americans elsewhere. Instead, they have been almost universally condemned, including by most (though not all) Republicans eager to disclaim any connection between their indefensible enabling of Trump for the past four years and the chickens coming home to roost.

Still, this is altogether different from, say, the responses to the Black Lives Matter marches following the murder of George Floyd, which undoubtedly generated lots of support elsewhere. Or of the de facto takeover of the streets of Washington by the Women’s March on January 21, 2017.

HLT: And what lessons do you think we can learn from what happened on Wednesday?

Levinson: That Josh Hawley (Stanford, Yale Law School) and Ted Cruz [’95] (Princeton, Harvard Law School) are unscrupulous opportunists who should be censured by the Senate precisely because, unlike the former Auburn football coach who is now the senator from Alabama, one might expect them to know better and to refrain from making truly frivolous argument garbed in their alleged devotion to the Constitution. Contrast Cruz with other Harvard alums, including Mitt Romney J.D./M.B.A. [’75] and Tom Cotton [’02].

But with regard to what can be learned, I’m inclined to quote Zhou en-Lai’s alleged response to the question of whether the French Revolution was a success: “It’s too early to tell.” I think that we will be learning very different lessons as each day goes by. I suppose I should also say that one of the potential lessons is the nature of white privilege, since it really is almost literally unthinkable that such remarkable tolerance would have been shown to violence committed by groups other than white men.

But one thing that might well be debated is whether it is actually better that the police response, for whatever reason, was so relatively mild, inasmuch as that avoided the creation of martyrs, had more been killed or seriously injured, who could be used to mobilize those who might be sympathetic to the Trumpian insurrection. Think in this context of Waco or even Ruby Ridge. One person was seemingly killed by the police, and there is some effort to martyrize her, but it doesn’t really seem (at least yet) to be taking with the public at large. The insurrectionists, at least so far, seem to have been remarkably undisciplined and quite stupid in many of their actions. That, again, is a purely political judgment, having nothing to do with any skills I have as a lawyer.