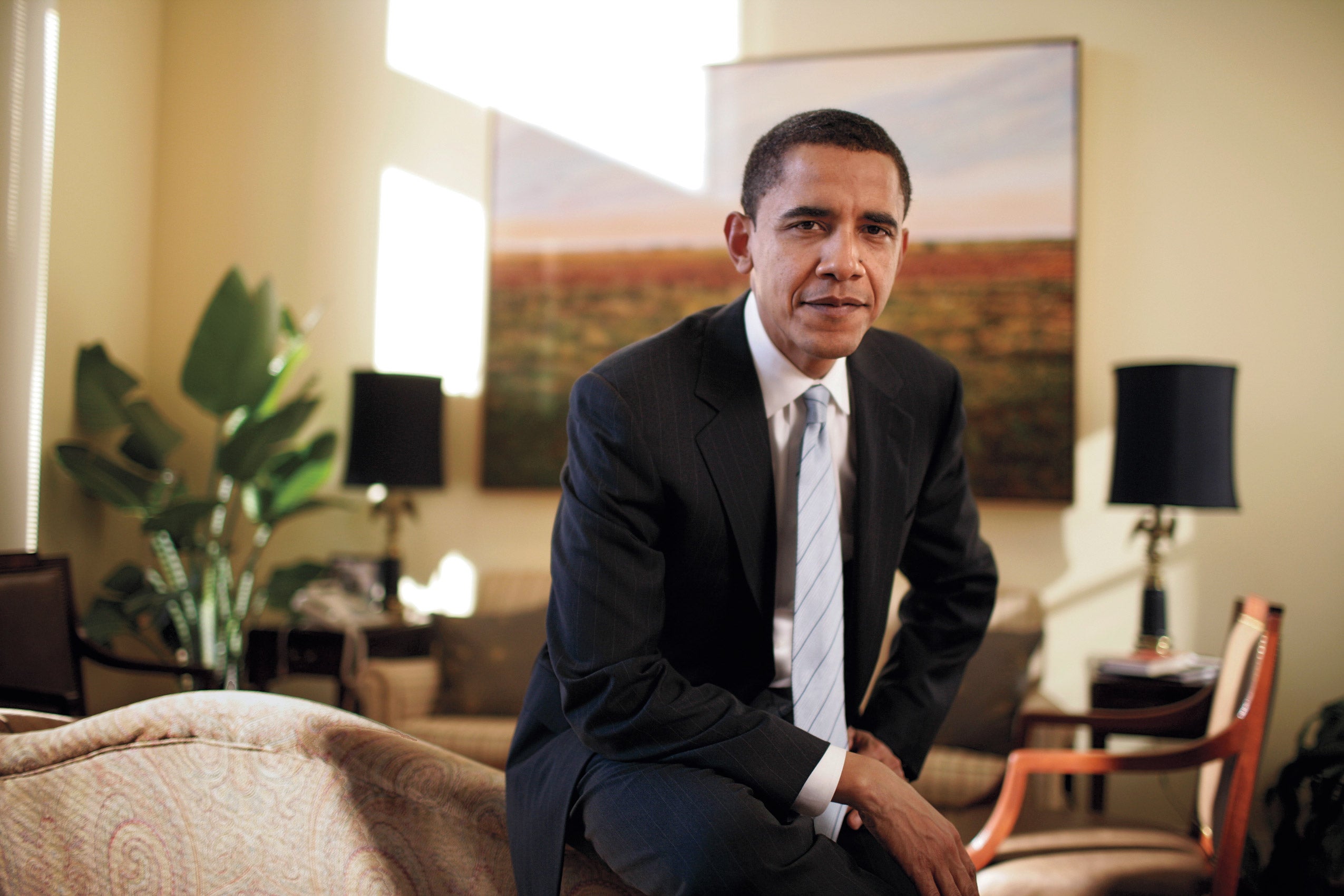

In law school, Barack Obama ’91 already looked—and led—like a future president

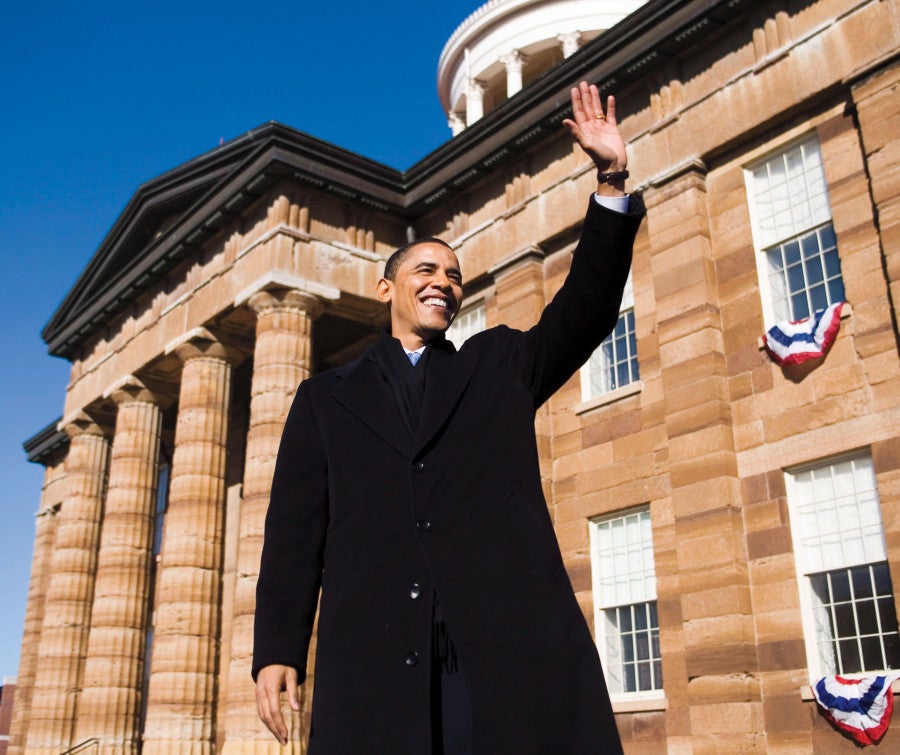

It was a frigid morning in February 2007 when Barack Obama ’91 officially announced his candidacy for president in front of the old state Capitol in Springfield, Ill. Seated in the front row of that shivering crowd of thousands were half a dozen of Obama’s law school friends, including Crystal Nix Hines ’90.

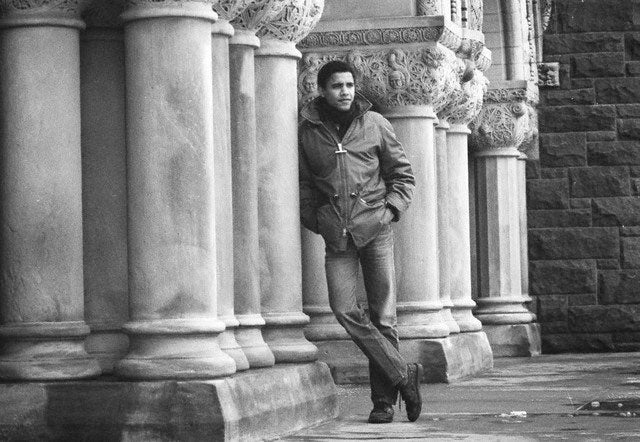

The newly minted presidential candidate whom Nix Hines applauded that day looked and sounded just like the classmate she knew at Harvard Law School—minus the leather bomber jacket and frayed jeans he preferred back then.

Nix Hines, a Hollywood television writer and producer, would go on to canvass voters on Obama’s behalf in Nevada and organize a fundraiser back home in Los Angeles.

As in Springfield, Obama and his wife, Michelle Robinson Obama ’88, would find many of their law school classmates and professors standing beside them at every step of the campaign that followed.

They cheered the Obamas on from Des Moines to Denver and finally in Chicago’s Grant Park, celebrating his victory on election night.

In between, they manned phones and knocked on doors. They donated money—and raised even more. They filled his kitchen cabinet of informal advisers and his campaign’s inner circle, offering both advice and quiet words of encouragement.

All shared a deeply felt dedication to a man many of them thought—even two decades ago in Cambridge—might one day be president.

“I went to Harvard Law School spending most of three years in poorly lit libraries, poring through cases and statutes,” Obama wrote in his memoir, “Dreams from My Father.” Over the last two years, he hasn’t dwelled publicly on his HLS days—not surprising during a campaign where the label “elitist” proved a potent political epithet.

But his time at HLS had an important impact on Obama, says David Mendell, who wrote the 2007 biography “Obama: From Promise to Power.”

“I don’t think you can discount how much that period helped educate him and played a big role in his development,” says Mendell, a former Chicago Tribune reporter.

It was as a law student that Obama first made history—and national headlines—when he was elected the first black president of the Harvard Law Review in the spring of 1990.

And as a law student, Obama met many professors and classmates who would prove helpful in his political rise from state senator to president of the United States in five years.

Each seems to have a story about how much Obama stood out.

Sure, Obama’s unique and, by now, familiar personal history set him apart. He arrived on campus at the age of 27 in the fall of 1988, older than many of his classmates, after a stint as a community organizer in Chicago.

Professor Kenneth Mack ’91, his classmate and friend, says Obama didn’t speak much at first about other aspects of his unusual background, including a childhood spent in Hawaii and Indonesia or the fact that his mother was white.

Most remarkable, given his complex identity, was how comfortable Obama seemed with himself. “Barack’s identity, his sense of self, was so settled,” recalled Cassandra Butts ’91, who met him in line at the financial aid office, in an interview with PBS’s “Frontline.” “He didn’t strike us in law school as someone who was searching for himself.”

Obama’s performance inside and outside the classroom attracted more notice than his distinctive personal story.

[pull-content content=”

Harvard Law School classmates and professors stood behind him at every step of his campaign

In the spring of his first year at law school, Obama stopped by the office of Professor Laurence Tribe ’66 inquiring about becoming a research assistant.

Tribe rarely hired first-year students but recalls being struck by Obama’s unusual combination of intelligence, curiosity and maturity.

He was so impressed, in fact, that he hired Obama on the spot—and wrote his name and phone number on his calendar that day—March 31, 1989—for posterity.

Obama helped research a complicated article Tribe wrote making connections between physics and constitutional law, as well as a book about abortion. The following year, Obama enrolled in Tribe’s constitutional law course.

Tribe likes to say he had taught about 4,000 students before Obama and has taught another 4,000 since, yet none has impressed him more.

Professor Martha Minow recalls: “He had a kind of eloquence and respect from his peers that was really quite remarkable.” When he spoke in her class on law and society, “everyone became very attentive and very quiet.”

Artur Davis ’93 still vividly recalls how much Obama inspired him with a speech he gave during orientation week on striving for excellence and mastery.

Davis, now a United States congressman from Alabama, insists he left that speech by Obama convinced he’d just heard a future Supreme Court justice—or president.

Obama displayed other traits, besides eloquence, that would define his success as a presidential candidate.

“You could see many of his attributes, his approach to politics and his ability to bring people together back then,” says Michael Froman ’91, who worked with Obama on the Law Review.

As a campus leader, he successfully navigated the fractious political disputes raging on campus.

By 1991, student protestors demanding that the school hire more black faculty had staged sit-ins inside the dean’s office and filed a lawsuit alleging discrimination.

Obama spoke at one protest rally but largely preferred to stay behind the scenes and lead by example, recalls one of the protest leaders, Keith Boykin ’92.

Obama opted against taking sides in the ideological disputes that often divided the politically polarized Law Review staff, casting himself instead as a mediator and conciliator.

That approach earned the enduring respect of Law Review members, including those not necessarily inclined to agree with his political views today.

“He tended not to enter these debates and disputes but rather bring people together and forge compromises,” says Bradford Berenson ’91, who was among the relatively small number of conservatives on the Law Review staff.

During the flurry of media attention following his election as Law Review president, reporters often asked Obama about his future plans.

He would reply that he envisioned working at a law firm for a couple of years before looking for community work—and perhaps running for office down the road.

By the time he graduated, though, Obama had declined an offer from Sidley Austin and set out on a career path that would include stints in Chicago directing a voter registration and education program and working at a civil rights law firm. He kept in touch with many of those he got to know best during law school as he moved on in his career.

Minow, who’d come to consider Obama a friend rather than just a former student, wound up serving with the then state senator on a national panel examining civic engagement in the late 1990s.

Obama proved just as engaging among the group of 33 distinguished and diverse panelists as he was in her class, Minow recalls.

After listening to him ably summarize everyone’s views at one meeting, Minow joined a group of panelists who went up to Obama and asked when he might run for president. He laughed at the idea, prompting many in the group to start calling him “governor.”

Minow was in the audience a few years later, in September 2005, when Obama—by then a U.S. senator—returned to the HLS campus as the featured lunchtime speaker for the second Celebration of Black Alumni.

That was after his speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, and he attracted a standing-room-only crowd that spilled into the adjoining courtyard and onto the stairs of nearby buildings where students gathered to listen.

He criticized the Bush administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina, which had devastated New Orleans just weeks earlier. But then he emphasized that simply blaming the Bush administration “lets us off the hook.”

He challenged his listeners to think of their own collective failure to help the urban poor prior to the disaster.

“The truth is,” Obama said, “we haven’t been entirely on the case either.”

Minow recalls that you could hear a pin drop under the tent as his emphasis on collective responsibility resonated with her and the rest of the audience.

Long before Obama’s Internet-based fundraising juggernaut began hauling in $50 million each month, Harvard Law School’s alumni and faculty provided an important network of potential donors and fundraisers.

Professor Tribe co-hosted a fundraiser in March 2007, a few months before he appeared in one of Obama’s early television ads in Iowa.

That spring, Froman, Obama’s law school classmate, helped organize a fundraising event in New York, one of the many he was involved in during the next year and a half.

Froman, who served as chief of staff to former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin during the Clinton presidency, was one of a number of law school colleagues who helped organize meetings for Obama around the capital after his election to the U.S. Senate and raised money for his political action committee.

Thomas Perrelli ’91 told The New York Observer last year that he was getting calls from classmates he hadn’t spoken with in years, saying, “Hey, I hear you’re still friends with Barack—what can I do?”

Jonathan Molot ’92, who, like Froman and Perrelli, served with Obama on the Law Review, hosted the first Washington, D.C., fundraiser for his presidential campaign at his home after having done the same in 2004 for his Senate campaign.

Molot, now a law professor at Georgetown University, hadn’t spoken with Obama in years but eagerly enlisted in the campaign of someone he, too, thought was presidential timber during law school.

“I’ve never in my life encountered anyone else about whom I said, ‘This person should be president,’” Molot says.

So many alumni attended that 2007 fundraiser at Molot’s home that Obama quipped, “I feel like I’m at a law school reunion.”

Law school friends of Michelle Obama’s pitched in too. She and Verna Williams ’88 were in the same 1L section and became moot court partners that year.

Williams stayed in touch after graduation and remembers the telephone call when Michelle mentioned the new guy named Barack she met at her Chicago law firm. When Obama ran for the Senate, Williams, now a law professor at the University of Cincinnati, and her husband, David Singleton ’91, helped raise money, and they did the same once he announced his bid for president.

[pull-content content=”

When Obama spoke at HLS after Hurricane Katrina, he challenged his listeners to think of their own collective failure to help the urban poor.

“He’s run a brilliant campaign, and she’s been just amazing,” said Williams before the election. “When you think about how difficult it must be to be married to this guy running for president and raising two young kids at the same time. But if anyone could do it, Michelle can.”

Meetings of Obama’s campaign policy advisers might have felt like a law school reunion too. His inner circle included several members of Harvard Law School’s class of 1991.

He tapped his law school classmate Cassandra Butts as a principal domestic policy adviser during the campaign. A former top aide to Congressman Richard Gephardt, she’d previously helped Obama set up his Senate office in 2005.

Julius Genachowski ’91 became a top adviser on technology policy, and Froman, a top Citigroup executive, was a key member of his economic team.

So, too, would Obama come to rely on the advice of Harvard Law School faculty, many of whom he’s known since his student days.

His roster of top legal advisers included Minow, Tribe, Charles Ogletree ’78, Cass Sunstein ’78, and Ronald Sullivan ’94, director of HLS’s Criminal Justice Institute. (Most were reluctant to discuss their roles in the campaign.)

Obama had turned to many of these professors for policy advice before. Sunstein, who first met him when both taught at the University of Chicago, was sitting in his office there one day when Obama called unexpectedly.

The senator wanted to talk about pending legislation regarding the warrantless surveillance program. For 20 minutes, he quizzed Sunstein on every aspect of the bill, pressing him with counterarguments for every point he raised.

Obama’s mastery of legal details impressed Sunstein—as did his insistence on thinking through every aspect of an issue before he made a decision.

“He’s just extremely thoughtful and open-minded and the farthest thing from an ideologue, especially when it comes to law,” Sunstein says.

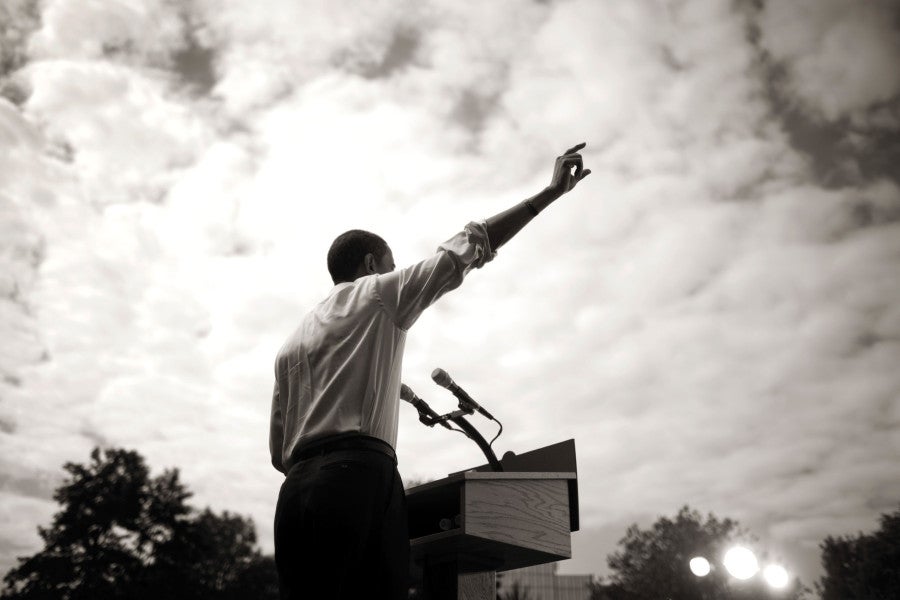

Several HLS professors offered more than policy advice once Obama announced his candidacy. For the first time in his life, Tribe wound up campaigning for a presidential candidate. He spoke before crowds of 50 to 500 undecided voters in libraries and cafeterias in New Hampshire and Iowa.

Sunstein signed up to be a campaign volunteer for Obama in Iowa in January 2008. After knocking on doors and manning a phone bank, Sunstein stood in the audience in Des Moines when Obama delivered his first victory speech of the campaign.

“Thank you, Iowa,” Obama began. “You know, they said this day would never come.”

Sunstein listened to many more of Obama’s speeches during the course of the campaign, but still thinks none topped that one in Des Moines.

“It had a kind of generosity and also a seriousness that I think defined the campaign at its best,” Sunstein says.

More than nine months after the Iowa caucuses, and nearly 20 years after Obama walked into his office in search of a research assistantship, Tribe stood in Chicago’s Grant Park, celebrating with nearly a quarter million others a victory many didn’t expect to see in their lifetimes.

Amid the excitement, the Obamas made time to speak with him in one of the VIP tents just off stage. They hugged him and thanked him for his role in educating Barack. Tribe found himself uncharacteristically tongue-tied—unable to express his thoughts and feelings. But the next morning, he put them into words.

“It was I,” Tribe wrote in a column for Forbes.com, “who owed thanks to them, thanks for the journey on which they had embarked to reclaim America for all who dare to hope.”

As the Bulletin went to press, several alumni mentioned in this story were named to serve on Obama’s transition team, including Cassandra Butts, Michael Froman and Julius Genachowski.