Harvard Law School has an original Magna Carta. But what does that mean?

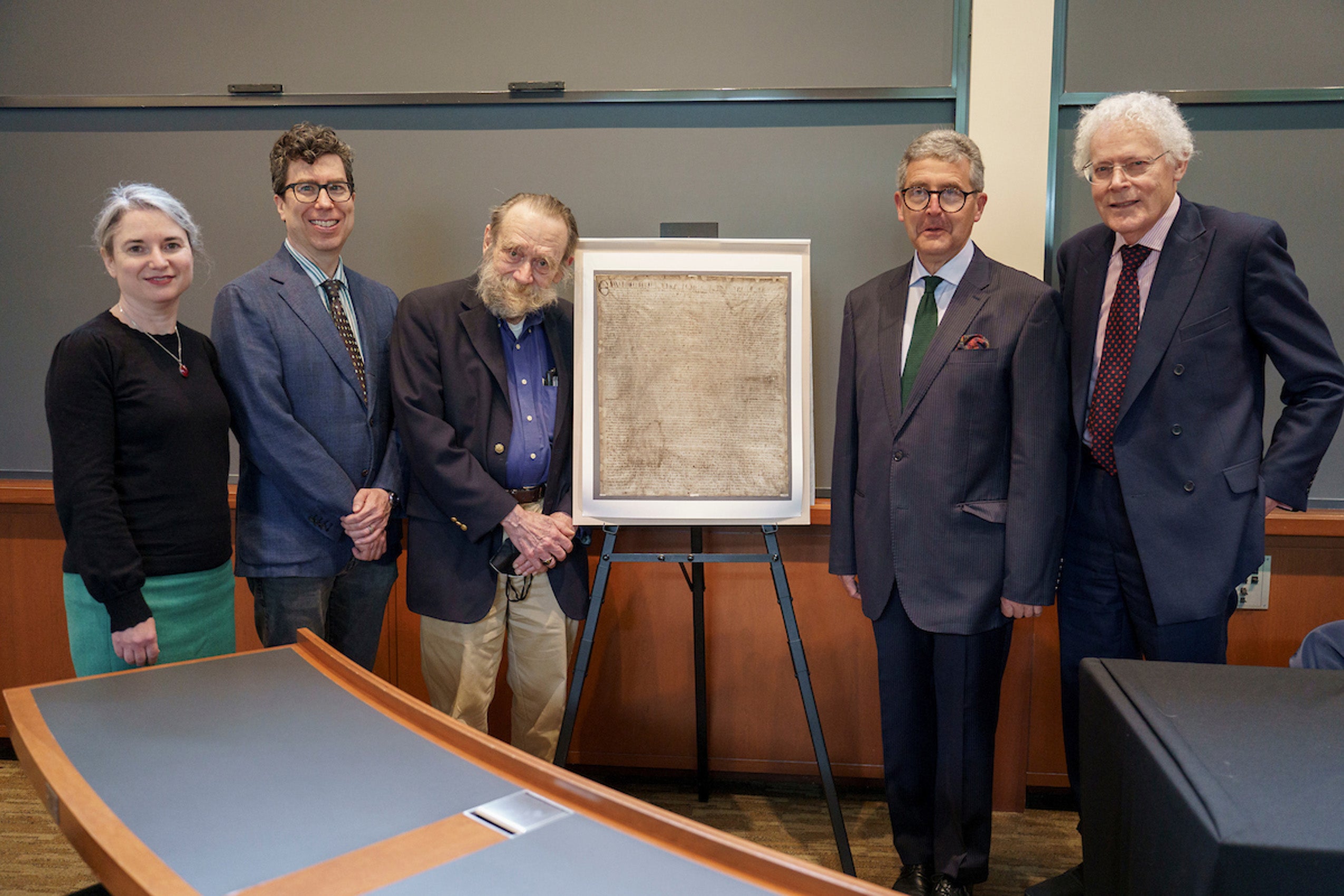

At a gathering last week, scholars and experts from the U.K. and Harvard Law School celebrated the discovery of an exceedingly rare, original Magna Carta in the Harvard Law School Library’s collection and discussed its significance to legal history and the world.

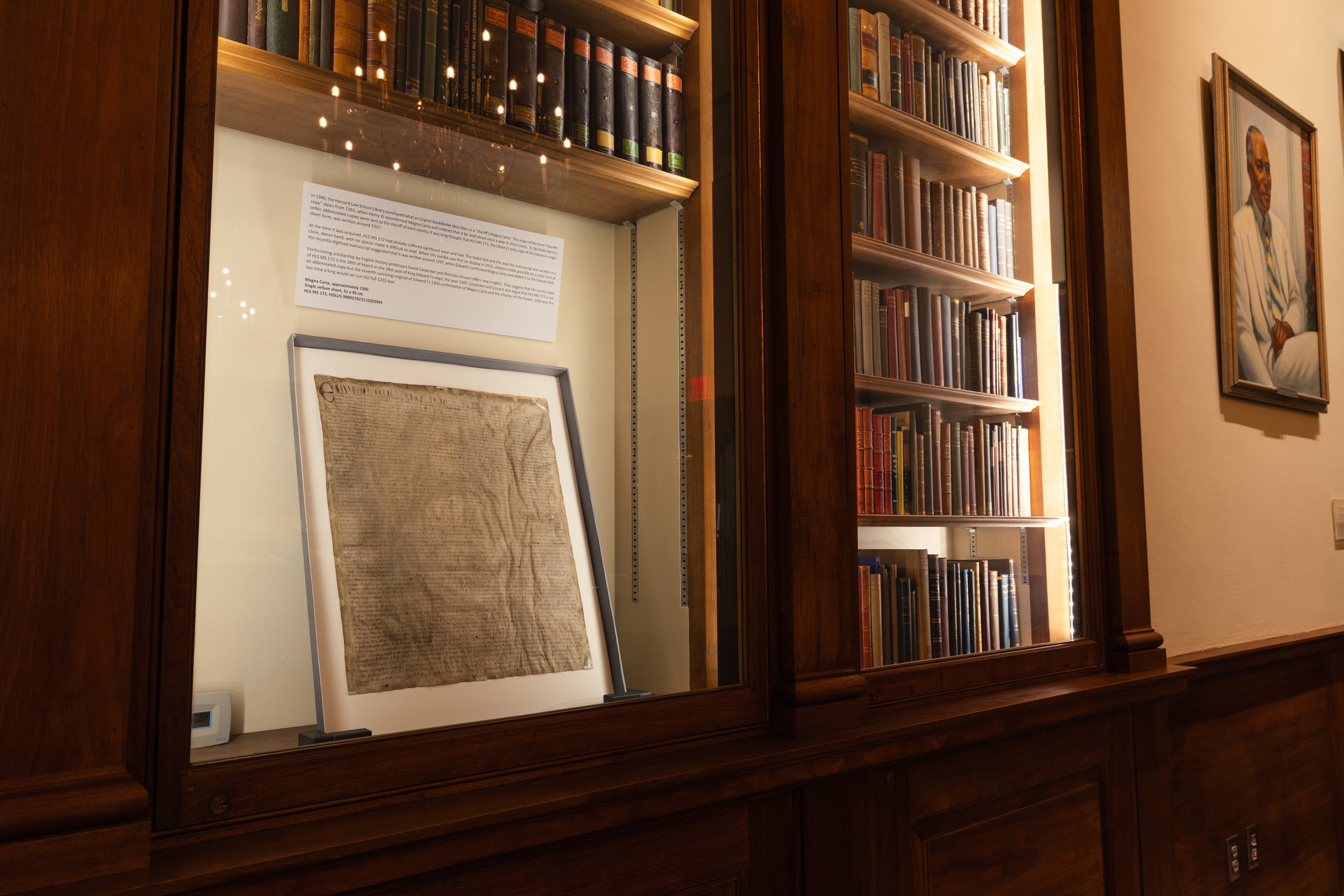

Purchased for $27.50 in 1946 and initially thought to be a copy, HLS MS 172 is instead a genuine issue from 1300, “the final, definitive, authoritative Magna Carta, and … what is on the statute book of the United Kingdom,” said David Carpenter, a professor of medieval history at King’s College London.

On June 17, Carpenter, who, with Nicholas Vincent, a professor of medieval history at the University of East Anglia, uncovered the manuscript’s history, spoke on a panel with two Harvard Law scholars, debating the discovery’s impact on the institution, the law, and the polity. What does it mean to be an “original” Magna Carta? What was this “Great Charter”? And is it even relevant today?

The daylong event also featured a discussion with experts from Harvard’s libraries, who shared how the university’s commitment to curating, preserving, digitizing, and making materials available to the public enabled this discovery and others like it.

Posted on the Harvard Law Library website in 2014, the Magna Carta manuscript was akin to a treasure hiding in plain sight.

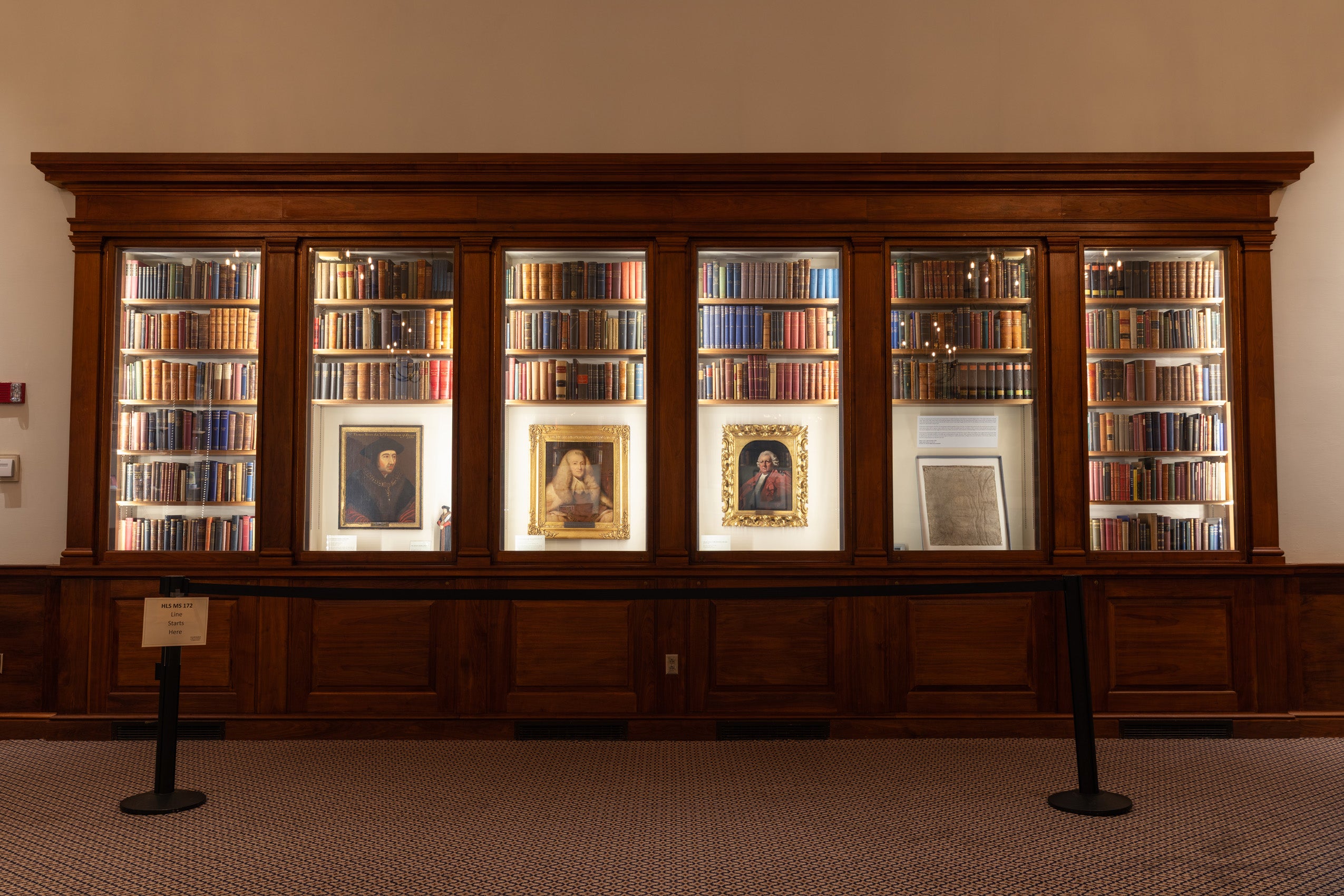

“Even before 2023, 172 was a well-loved document,” said Amanda Watson, the assistant dean for library and information services at Harvard Law School Library. “It was something that we cherished, [that] we saw something special in it. That’s why we bought it and digitized it.”

Harvard’s Magna Carta

In a discussion led by Jonathan L. Zittrain ’95, the George Bemis Professor of International Law at Harvard and vice dean for library and information resources, the two British researchers, Carpenter and Vincent, were joined by Elizabeth Papp Kamali ’07, Austin Wakeman Scott Professor of Law, and Charles Donahue, Paul A. Freund Professor of Law, to discuss the significance of Harvard’s Magna Carta and the charter’s place in the Western legal tradition.

Because Magna Carta binds the crown to the rule of law, many scholars consider it a key step in the evolution of human rights against oppressive rulers. First issued in 1215 by King John, the charter was reaffirmed in 1300 by King Edward I, who sent an edition to the former parliamentary borough of Appleby in Westmorland, England. This manuscript was later owned centuries later by antislavery campaigners Thomas and John Clarkson, then First World War flying ace, air vice-marshal Forster ‘Sammy’ Maynard CB, before being sold at auction to Harvard in the late ’40s.

John Goldberg, the interim dean of Harvard Law, opened the discussion by thanking all involved for their part in uncovering HLS MS 172’s story.

“Magna Carta might be described as memorializing and affecting an irrevocable grant of basic liberties and rights by the English monarch to a group of rebellious barons,” Goldberg said. At the same time, he added, it has become something much greater: a charter of “broader and deeper principle.”

“The rediscovery of this critical early attestation to core Anglo-American political commitments to liberty, to limited government, and to the rule of law, thus happily gives us occasion to recognize and reaffirm the shared values that continue to bind our two nations,” said Goldberg.

Zittrain wondered why the researchers, who first alighted upon a digitized version of Harvard’s Magna Carta on the library website in 2023, suspected it was an original. And what is an “original,” anyway, he asked.

The British researchers explained that, after requesting high-quality scans and advanced photographs of HLS MS 172 from the library and comparing the manuscript to other extant versions from 1300, they were able to determine that it had, in fact, been issued under King Edward I’s seal.

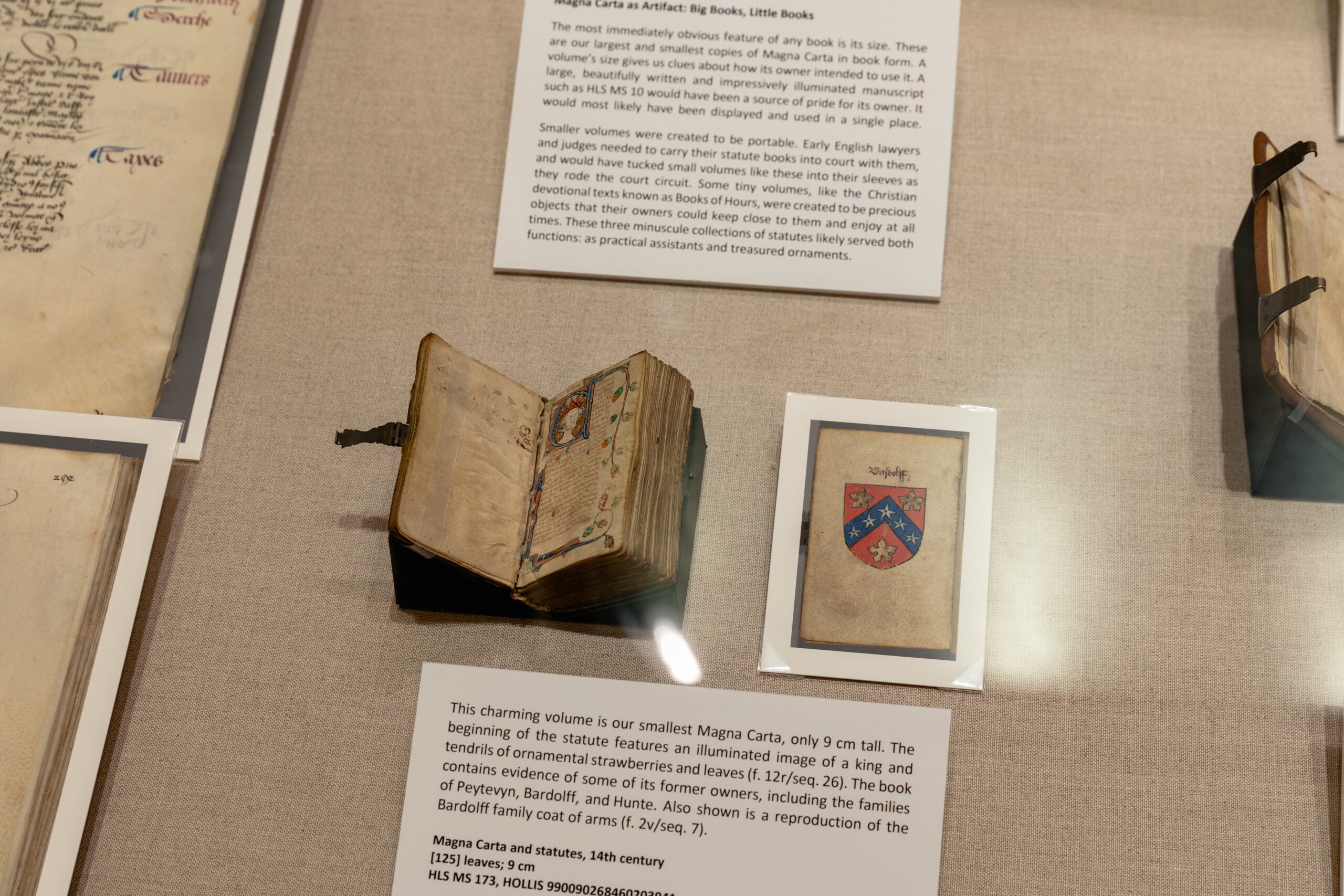

“There’s plenty of difference between an original, which is set out by the king, and it’s written by the scribes and so on,” Carpenter said. “Once you’ve got an original, anyone can copy it, and Harvard Law School, in its collection of statute books, [also] has huge numbers of copies.”

Vincent compared the official Magna Carta to the modern yellow pages, a printed telephone directory for businesses. When a new version of the yellow pages comes out, he said, “you throw the old one away.”

“We’ve got a document that belonged to one of the key figures in the antislavery campaign that then belonged to a man who defended Malta against the powers of fascism in the Second World War. What better provenance could you possibly invent?”

Nicholas Vincent

“What you’ve got here is the most up-to-date version of that Magna Carta yellow pages,” Vincent said.

Carpenter was even more effusive about Harvard’s manuscript. “You’ve got the best. 1300 is the best final Magna Carta. It’s far better than 1297, it’s better than all the previous versions,” because it has an extensive witness list, he added.

Carpenter said he believed there was something of value — beyond money — in possessing an original. The manuscript is “very, very evocative and powerful,” he said. “Although I can look at all your lovely copies in the statute books, I don’t think any of them have got the emotive power or the authority of an actual original, because they all derive from the original.”

Even the manuscript’s provenance is fascinating, Vincent said. “We’ve got a document that belonged to one of the key figures in the antislavery campaign that then belonged to a man who defended Malta against the powers of fascism in the Second World War. What better provenance could you possibly invent?”

What is Magna Carta?

Legal historians often point to Magna Carta as a foundational text that creates some rights and liberties for “free men” — however narrowly defined — and establishing the rule of law, to which the king himself was subject.

To Carpenter, Magna Carta does more than simply assert “high-sounding platitudes.”

“It’s doing it in a very nitty gritty way across the whole range of royal government,” he said, adding that it applied to justice, finance, and even local governments.

While some might view Magna Carta as a “selfish baronial document,” Carpenter said, “even at its start, it reached out to a wide constituency. It reached out to the church, to towns, to knights, to free men.”

In Vincent’s view, much of the charter is still relevant today. He pointed to a provision that addresses tariffs as one particularly timely example. And provisions that feel archaic — such as clause 33, which bars “fish weirs” from the Thames — may still have resonance, he argued. “It is actually freedom of navigation, which is a rather important principle. So even behind what looks like total anachronism, you can find something of relevance today.”

Ultimately, Magna Carta was part of a movement toward holding the powerful to account, at least to some degree.

“Why are tyrants the way they are?” asked Vincent. “Well, they do not observe the law. They do not allow the law to be read, and they ignore accepted custom. Again, it’s extraordinary how current some of those debates can be seen.”

Because the document was copied and studied by so many people over the centuries, Carpenter said, “That’s how it sunk such deep roots into the English polity, from whence it ultimately went round the world.”

This lesson is also relevant today, he suggested. “It’s vital to actually know what is in your constitution. Because unless you know what’s there, you can’t even begin to think of how it might be enforced.”

A different view

Harvard Law’s Professor Kamali, an expert on English legal history and criminal law, said that she devotes an entire lecture to Magna Carta. But she added that she believes something more important happened in 1215, the date it was first issued. In Kamali’s view, the more momentous advance that year occurred at the Fourth Lateran Council, a gathering convened by Pope Innocent III in Rome, which ushered in the use of jury trials in felony cases in England.

“Historically, I have not put out HLS MS 172 in the items on display” for students, Kamali continued. She instead prefers to exhibit HLS MS 175, which contains not only Magna Carta, but a succession of 13th century statutes that built on the charter.

To Kamali, Magna Carta was influential, but not singular, in its ideas. She pointed to Hungary’s Golden Bull as another contemporaneous document that limited the power of the nation’s royals. “I think Magna Carta, in a way, is part of a much broader movement in Western Europe towards the articulation of rights and liberties and the articulation of limitations on the power of monarchs.”

“I think Magna Carta, in a way, [was] part of a much broader movement in Western Europe towards the articulation of rights and liberties and the articulation of limitations on the power of monarchs.”

Elizabeth Papp Kamali

Professor Donahue was similarly subdued, joking that he was going to “throw a bit of cold water on the party.”

He first referred to a paper he wrote for the anniversary of Magna Carta, regarding a statement by William Stubbs, an English historian. “Stubbs’ statement [was] that all of English constitutional history is but a commentary on this charter. I decided that that was not quite right.”

And while it might be exciting to have an original Magna Carta in Harvard’s collection, Donahue argued that it contains little new for experts in the field to study. “Everything in it is totally known. There is nothing to be discovered out of this document.”

Even so, Kamali believed that there could be value to the original because of the emotional power that viewing such documents can have. “Massachusetts being sort of the cradle of American liberty, this also seems like a special place for having some way of displaying, in a public sense, the actual original.”

Making Magna Carta available to the world

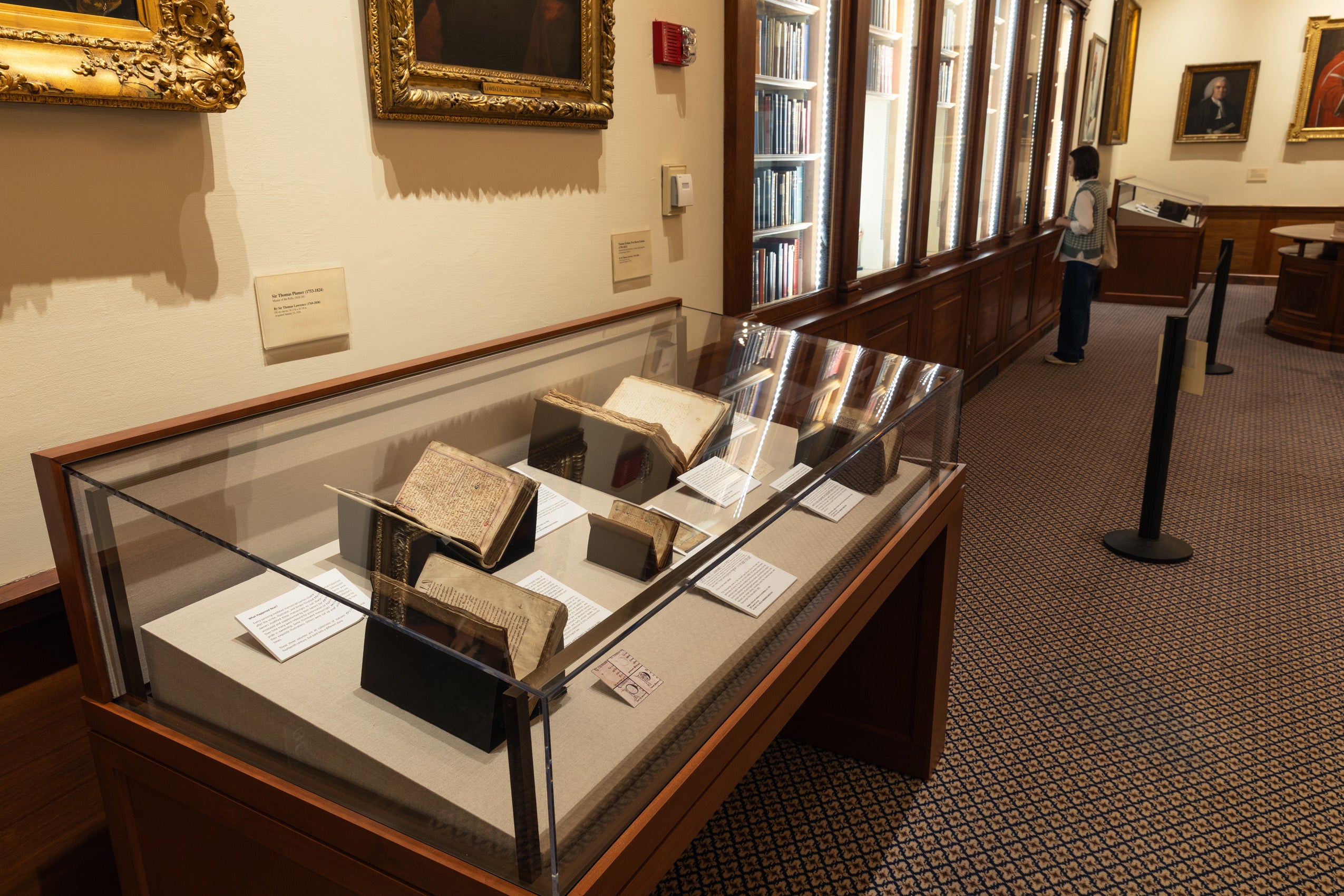

Earlier in the day, a group of librarians and conservators, moderated by Watson from the Harvard Law School Library, discussed how they curate, preserve, digitize, and make available the nearly 20 million items in Harvard’s collections — including HLS MS 172.

“This story really exemplifies what we care about in libraries, and that’s enabling scholars’ discovery of engagement with a vast range of information and cultural resources and preserving those resources for future generations,” said Martha Whitehead, the vice president for the Harvard Library and University Librarian and Roy E. Larsen Librarian for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

According to John Overholt, a curator at the Harvard University Houghton Library, one of the main goals of all Harvard libraries is ensuring public access to materials, including through exhibitions, courses, and online resources.

“It’d be sad and kind of pointless if we accumulated all of this amazing historical stuff and just kept it locked in our basement and did not make it accessible to anyone,” he said.

That is precisely why Harvard Law School Library continues to digitize its materials and make available online items like HLS MS 172, said Leah Prescott, its former associate director for collections.

“We digitize to provide access to the rich resources that we have in our collections to people who cannot visit in person,” she said. “This [discovery] is an absolutely wonderful case to prove that that is a valuable reason for digitization.”

Harvard libraries’ role in the discovery did not end with digitization. After Carpenter and Vincent contacted Prescott and her team in 2023, Harvard conservators worked with the British researchers to produce additional scans of Magna Carta, then special UV photographs of the manuscript, which helped them analyze the document from abroad.

This is but one example of the kind of surprises originating from the university’s vast collection, said Debora Mayer, a conservator at Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center. “It’s fantastic and it happens on a daily basis … small discoveries happening with students and faculty all the time, maybe not the Magna Carta, but forwarding research.”

Finally, Prescott said that Harvard’s work with HLS MS 172 will endure, as the library continues to protect and make the manuscript available for future generations.

“We digitize so that we can see what is there, but we preserve so that we can believe what it is that we are seeing,” she said.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.