Intelligent minds have long differed on the U.S. Constitution’s role as a blueprint for democracy. Some see it as the sacrosanct product of an enlightened era, its text to be followed literally. Others say that the Constitution must be interpreted more generally in order to apply its principles to current times.

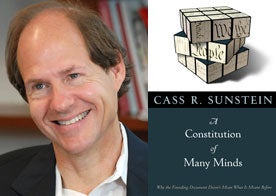

In his new book, “A Constitution of Many Minds: Why the Founding Document Doesn’t Mean What It Meant Before,” HLS Professor Cass R. Sunstein ’78 argues that these interpretations needn’t be mutually exclusive. According to Sunstein, who was chosen by President Barack Obama ’91 to head the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs earlier this year, the manner in which the Constitution is interpreted is not as important as whether or not the interpretation is the product of a proper consensus. To answer that question, Sunstein turns to a theory, made popular by James Surowiecki’s 2004 book, “The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economics, Societies and Nations,” and applies the “many minds” approach to constitutional interpretation.

To Surowiecki, crowds produce better decisions than individuals, but only if they are sufficiently diverse and independent. In “A Constitution of Many Minds,” Sunstein looks at the various modes of constitutional interpretation and, like Surowiecki, seeks to identify when many minds arguments are strong and when they are not. He focuses on three approaches to constitutional interpretation: traditionalism, which holds that courts should be reluctant to alter established practices; populism, which argues that current beliefs should have stronger influence on judicial decision-making; and cosmopolitanism, or the belief that U.S. courts need to pay greater attention to global thinking.

Sunstein points out that while each camp has a different approach, they all lay claim to many minds substantiation. Traditionalists contend that long-standing societal practices over generations generally trump current opinion. Populists believe that if most people hold a certain belief, courts should pay attention. Cosmopolitans say U.S. courts should consider populism on a global scale.

So which approach is correct? The answer, according to Sunstein: It depends.

“[T]raditionalism is quite attractive in the domain of separation of powers, federalism, and gun rights,” he writes. “In these domains, what has been done in the past is highly relevant to what should be done in the present. But when we are speaking of equality, traditionalism has much less force. In that domain, the present knows more than the past, and the former should yield to the latter.”

Other constitutional scholars on the HLS faculty have lauded Sunstein’s book as a strong scholarly contribution. The book “clearly frames critical questions about the role in constitutional law of rationality, tradition and the wisdom of crowds, extended over many generations,” says Professor Adrian Vermeule ’93, whose own 2008 book, “Law and the Limits of Reason,” also explores the many minds theory and judicial decision-making.

“Particularly impressive is the idea … that ‘there is nothing that interpretation just is,’” Vermeule says. “In other words, that no school of constitutional interpretation can lay claim to superiority on strictly conceptual grounds; rather, what matters are the capacities of the institutions doing the interpretation.”

“A Constitution of Many Minds: Why the Founding Document Doesn’t Mean What It Meant Before” was published by Princeton University Press. The book’s introductory chapter (excerpted below) is available on the publisher’s website.

INTRODUCTION

Jefferson’s Revenge

AN OLD DEBATE

In the earliest days of the American Republic, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson offered radically different views about the nature of constitutionalism in their young nation. Madison insisted that the Constitution should be relatively fixed. In his view, the founding document had been adopted in a uniquely favorable period, in which public-spirited people had been able to reflect about the true meaning of self-government. Miraculously, We the People had succeeded in producing a charter that would be able to endure over time. The Constitution should be firm and stable; the citizenry should take the document as the accepted background against which it engages in the project of self-government.

To be sure, Madison did not believe that the Constitution ought to be set in stone. He accepted the Constitution’s procedures for constitutional amendment; indeed, he helped to write them. But he thought that amendments should be made exceedingly difficult. In his view, constitutional change ought to be reserved for “great and extraordinary occasions.”Madison wanted the work of the founding generation to last; alterations should occur only after surmounting a formal process that would impose serious obstacles to ill-considered measures based on people’s passions or their interests. This, then, was a key component of Madison’s understanding of the constitutional system of deliberative democracy: A system in which the constitutional essentials were placed well beyond the easy reach of succeeding generations.

Thomas Jefferson had an altogether different view. Indeed, he believed that Madison’s approach badly disserved the aspirations for which the American Revolution had been fought. Jefferson insisted that “the dead have no rights.”He thought that past generations should not be permitted to bind the present. In his view, the founders should be respected but not revered, and their work ought not to be taken as any kind of fixed background. In a revealing letter, Jefferson contended that those who wrote the document “were very much like the present, but without the experience of the present.”In other words, the present knows more than the past, if only because it is, in a sense, older. For these reasons, Jefferson urged that the Constitution should be rethought by the many minds of every generation, as the nature of self-government becomes newly conceived in light of changing circumstances. We the People should rule ourselves, not simply through day-to-day governance under a fixed charter, but also by rethinking the basic terms of political and social life.

According to the standard account, history has delivered an unambiguous verdict: Madison was right and Jefferson was wrong. The United States is governed by the oldest extant constitution on the face of the earth. In most of its key provisions, it remains the same as it was when it was ratified in 1787. Many of its terms have not been altered in the slightest. Just as Madison had hoped, the work of the founders endures. For all his ambition, Madison would likely have been amazed to see that well over two hundred years after the founding—roughly the same number of years that separate the birth of the document from the birth of Shakespeare—much of his generation’s labor would continue to govern in essentially unaltered form. Read more.