One hundred years ago, Owen Wister, a native of Philadelphia and an HLS graduate, published the definitive Western novel

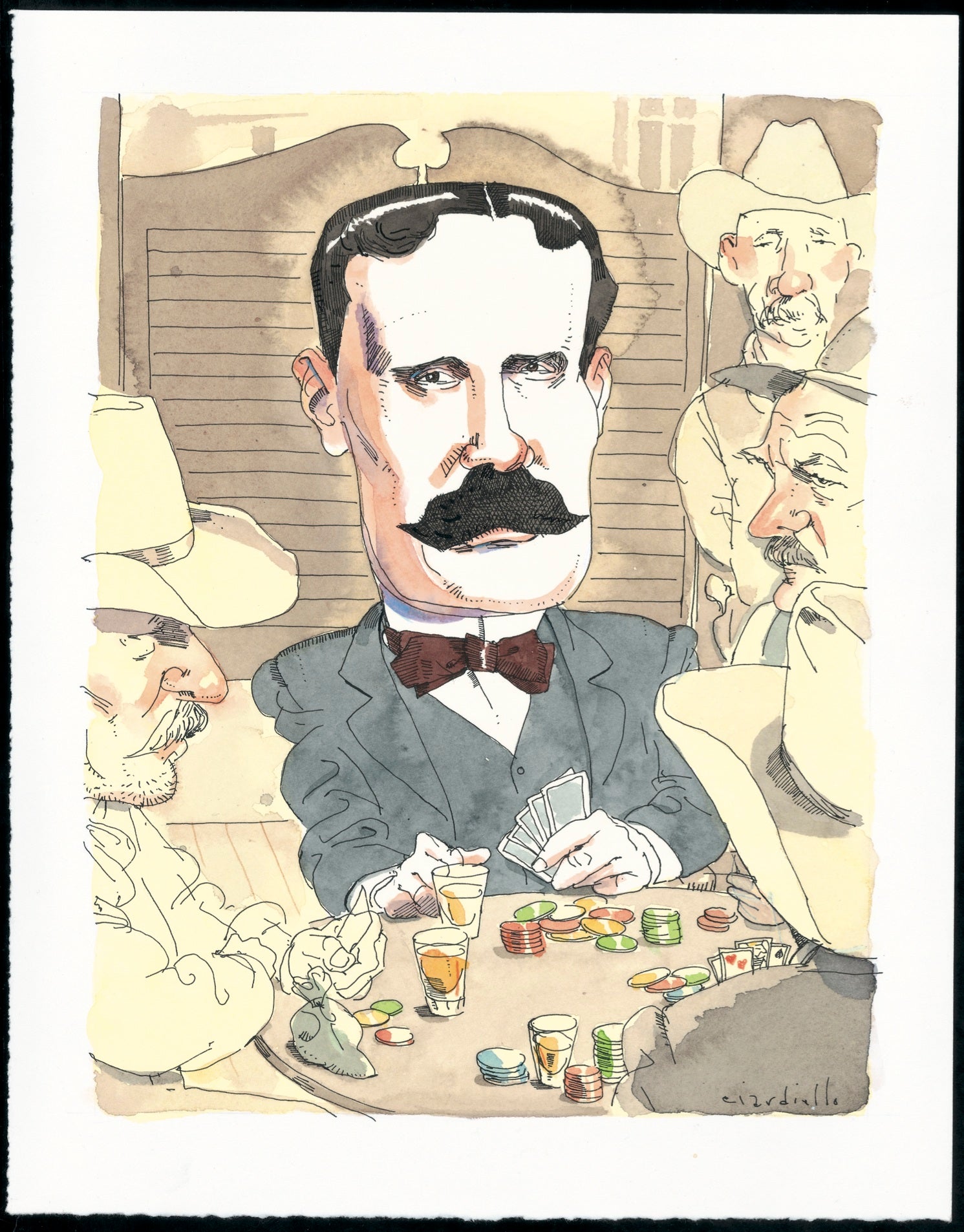

Another poker game in a flyblown Wyoming saloon. The tall, dark ranch hand takes his sweet time. “Your bet, you son of a bitch,” the dealer says. The other men around the table brace themselves for one of those small bloodbaths that keep them on the toes of their cowboy boots. The stranger draws his pistol, but it’s his words that disarm his opponent. “When you call me that,smile,” he says.

And Owen Wister does smile. This is his showdown, in his saloon. At least it comes from his imagination– fertile ground, considering the greatest danger in his life is getting a paper cut in his Philadelphia law office. But Wister and his ranch hand did have something in common. They were both going places.

After Harper’s magazine published stories featuring the cowpunch from Virginia, Wister went on to write the novel that made the two of them famous, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains. By then the 1888 HLS graduate had abandoned his Philadelphia law practice to write full-time. Wister knew more about salons than saloons, but his story of the handsome, honest cowboy who forges frontier justice and wins his woman was a wild success, running through 15 printings within eight months of its publication in 1902. It also won praise from such luminaries as Henry James 1882-’83 as well as President Theodore Roosevelt, Wister’s friend from Harvard College, who had urged him to transform his recollections of summers spent in Wyoming into the great American novel about the disappearing West.

Wister wrote other fiction, including Philosophy 4, set at Harvard College, and Lady Baltimore, perhaps now most remembered for the layer cake of the same name served up to its Charleston characters. There were histories and biographies as well. And last fall–63 years after his death–a new title, Romney, appeared under his name, a fragment of an unpublished novel about his hometown of Philadelphia.

Yet it’s The Virginian for which Wister is remembered. In 1977 the Western Writers of America voted it the top Western novel of all time. Writer Loren Estleman, the organization’s president, calls it a classic. He praises the Joseph Conrad-like restraint of Wister’s style, “deceptively flat, but with a great many tremors below the surface.”

And beyond the book’s literary merit, he says its staying power comes from Wister’s ability to create an American myth. “If I were to speak to an alien from outer space about what the West was all about,” said Estleman, “I’d ask him to read The Virginian.“

While The Virginian remains in print, its romantic view of the West has gained even wider circulation beyond its pages. There were the movie adaptations, starring Joel McCrea and Gary Cooper as the Virginian, and then the ’60s television series of the same name, so loosely based on the original that the villain in the novel becomes the Virginian’s best friend. But the book’s influence has spread well beyond these namesake productions. From the fast draw, to the town that’s not “big enough for the both of us,” to the man with no name, the stuff of Wister’s novel has become the clichés of print and screen about the American West.

Last spring a Harvard Law librarian discovered a letter from the author of The Virginian in a backlog of uncatalogued materials. In it Wister describes the way the novelist creates his characters through a distillation of “all he has seen, heard, and felt.” He goes on to say that “the growth of one’s own characters lies mysteriously outside one’s intellectual control.” If the many reincarnations of the tall, dark stranger with the quiet swagger are any indication, Wister’s words were truer than he knew.